Why are orcas attacking boats in the Iberian Peninsula?

Why are orcas attacking boats in the Iberian Peninsula?

Emer Keaveney / ORCA SciComm Team I 31st May 2023

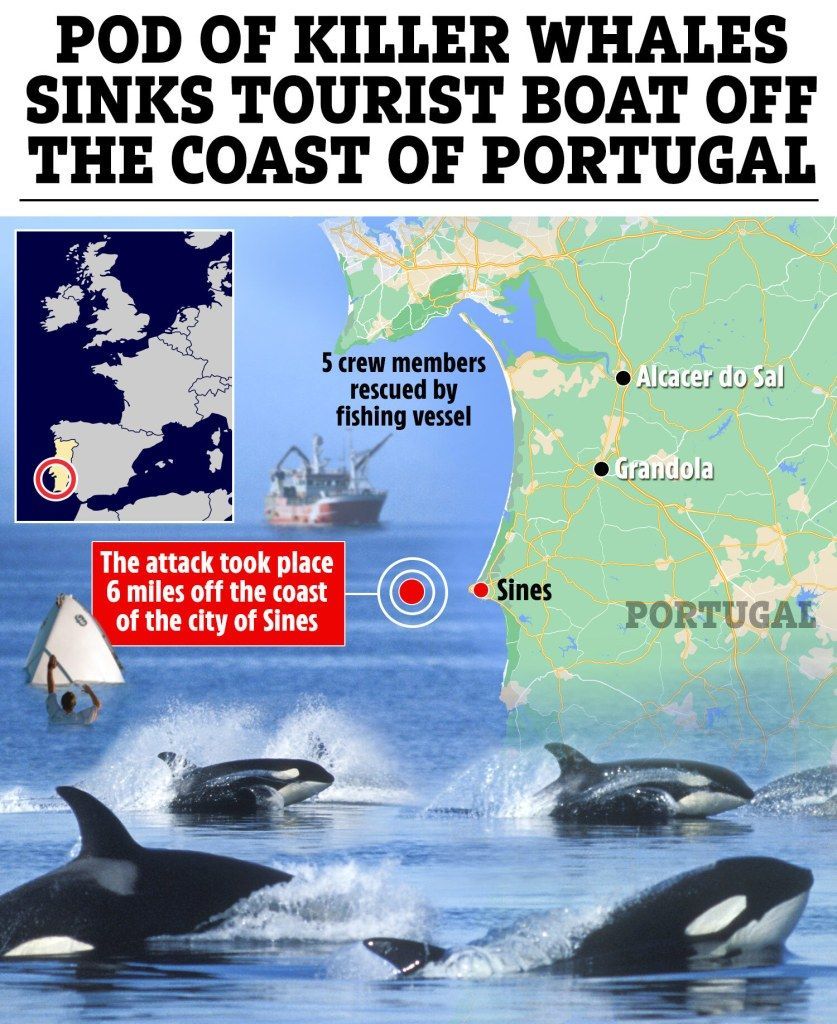

In the maritime waters of the Iberian Peninsula, more than 50 noteworthy incidents have occurred where yachts find themselves at the mercy of a pod of orcas within the confines of the Strait of Gibraltar. Recent investigations suggest that these incidents involve a specific subpopulation of killer whales responsible for the attempts to capsize marine vessels, and these occurrences can be traced back to one traumatized whale from May 2020. The suspected progenitor of this unusual behaviour, a female orca, reportedly endured a distressing encounter with a boat.

The majority of the reported incidents encompass orcas engaging in unprecedented actions, such as gnawing at, distorting, and severing the rudders of sailing boats. This provokes intriguing queries – how did these aquatic creatures acquire this distinctive behavioural pattern, and what could possibly be their motive?

Any response to this conundrum, whether it be from NGOs or from renowned scientists in the field of marine mammalogy, must be regarded as conjecture due to the limited comprehension we currently have of killer whale motivations. The challenge facing biologists, and indeed the scientific community at large, is unraveling the development of this peculiar behavioural phenomenon in these oceanic predators.

The absence of apparent benefits that enhance survival or reproduction, such as food, suggests this behavior is improbable to have emerged as an adaptive trait, which conventionally contributes to an organism's survival in its environment. An adaptive trait is typically understood as one that furnishes a direct evolutionary advantage by aiding the organism in crucial life functions such as securing nourishment, attracting a mate, or successfully rearing offspring.

While our understanding of the motivations behind such behaviors is limited, we can indeed observe and describe them. Documented instances include solitary orcas and groups alike exhibiting distinctive behaviors that do not immediately appear to be adaptive. These vary from one pod seemingly engaging in a fleeting trend of balancing deceased salmon atop their heads, to another demonstrating vocal mimicry of sea lions. The latter could potentially have adaptive implications, such as duping sea lions into perceiving orcas as fellow sea lions rather than predators, yet there exists no concrete evidence supporting this hypothesis.

Some behaviors do seem to yield certain advantages. For instance, orcas in captivity have been observed learning to regurgitate fish to use as bait for gulls, which they seem to find more palatable than the regurgitated fish. However, the emergence and propagation of these boat attacks align well with the description of a passing craze. It remains uncertain as to the duration of this behavior.

If there were to be an adaptive rationale for this behavior, our hypothesis points toward the role of curiosity, which can sometimes culminate in critical innovations pertaining to the discovery of new food sources. These newfound sources can then be shared among the group.

What theories exist concerning the transmission of this behavior amongst the killer whales inhabiting this region?

It is plausible that this behavior initially took root in individual orcas and then proliferated via social learning. Scientists have recently contributed to the body of research on this topic with a publication discussing a similar trend observed in bottlenose dolphins, where a specific dolphin was identified as the instigator of a tail-walking behavior acquired during a transient period in captivity.

This narrative aligns closely with a scholarly account of the recent yacht capsizing incident, where a particular individual was pinpointed as the probable originator. This orca is thought to have developed this behavior as a consequence of a past traumatic event, potentially a collision with a boat rudder as suggested by the account.

While discerning the exact reason is inherently challenging, it is apparent that the behavior has permeated her group. It would be arduous to interpret this dynamic without attributing it to some form of social learning, essentially the dissemination of information.

Have there been instances of killer whales exhibiting such behavior in the past?

In the course of conducting a research survey in the waters surrounding St Vincent in the eastern Caribbean, there hae been cases of orcas swimming close to vessels. The vessels, similar to those involved in these notable interactions, were comparable in size to a large whale, such as a humpback. It is possible they were merely scrutinizing the vessel, yet there were no instances of it escalating to any form of physical contact.

The perception was that they exhibited a keen interest in the boat's propeller, and the currents it produced - they ventured so close on one occasion that seemed the driver of the boat was compelled to disengage the engine to avoid inflicting any harm. Hence, the act of approaching boats is not a novel behaviour for orcas. However, inflicting damage on them in such a determined manner is, indeed, unprecedented in many experiences with orcas.

This kind of behaviour, of course, has been documented in other species - notably, sperm whales (Physeter

macrocephalus), inspiring the legendary narrative of Moby Dick. This story is a composite of accounts about a white whale known as "Mocha Dick" sighted off the coast of South America, coupled with the tale of the whaling ship Essex, which was purportedly sunk by a massive sperm whale in equatorial waters

Is the critically endangered status of the subpopulation of orcas instigating these attacks relevant in any way?

It cannot be perceived to be particularly pertinent to the emergence and diffusion of this behavior, however, it is of paramount importance in terms of how people approach the management and conservation of this population of orcas.

If these killer whales persist in attacking boats, it will inevitably complicate their protection efforts. Engaging with rotating propellers not only amplifies the risk of injury to these marine mammals but also poses a danger to humans - from causing injuries to crew members to sinking vessels - which will inevitably generate political urgency for intervention.

Certainly, small vessel operators are not compelled to traverse the areas along the Atlantic coastlines of Spain and Portugal where these encounters with orcas have been occurring. Restricting their access would effectively mitigate the problem, however, for many boat operators and owners, these are their shortest routes, while veering offshore presents more perilous voyages. The prospect of losing tourism revenue should these vessels cease operation will further intensify the call for a long-term resolution.

There exists a possibility that some might advocate for the control of these orcas, even to the extent of advocating their termination, should they persist in posing threats to human lives and livelihoods. This gives rise to significant ethical dilemmas regarding our interactions with these creatures.

Should we, as the species that wields the greatest influence, withdraw small, vulnerable vessels from the orcas' habitats in acknowledgement of a changing relationship with the sea, a sea we know is deteriorating due to human activities? Alternatively, should we claim the right to navigate at will and manage any nonhuman animals that obstruct our activities, even if it means exterminating them?

Historically, the latter perspective would have almost certainly dominated, and perhaps it will do so in this situation as well. However, it is a question that needs to be addressed by society at large, rather than just scientists. The course of action that the pertinent authorities ultimately choose will indeed be revelatory.

Reports suggest that a 'traumatized' victim of a boat collision might have triggered this behavior. Are ideas of mutual support and self-defense among killer whales considered far-fetched?

We perceive these as credible theories. The authors of the recent research paper outline it as one among various suppositions about the emergence of this behavior, with the intensifying pressure on their habitat and the concept of natural curiosity being other possibilities (the latter I believe to be the most probable).

The idea of collective self-defense among cetaceans (a group encompassing whales, dolphins, and porpoises) is far from being absurd. We possess accounts of sperm whales collectively rising to defend one another when confronted by orca attacks, for instance. Solidarity, however, is a more subjective topic, and our inability to access the internal mental states of these creatures limits our understanding of its prevalence.

We can, nevertheless, refer to a different species of cetacean: humpback whales have been observed aiding other species, notably seals, when they are under orca attack. The scientist who spearheaded the description of this behavior, Robert Pitman, regards it as "inadvertent altruism" predicated on a simple heuristic: "When you hear a killer whale attack, go break it up."

These accounts raise intriguing questions about the motivations underlying orcas' attacks on boats, questions to which we are currently unable to provide definitive answers. It's not beyond the realm of possibility that these orcas perceive a common adversary in humans - but it's equally plausible that they possess no such notion.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE