The ArcticUnicorn: Soundscape in a Glacier Fjord.

A team of geophysicists from the Hokkaido University in Japan recorded narwhals’ vocalizations in a Greenlandic glacier fjord. The scientists were able to approach this elusive whale species with help of Inuit hunters. These recordings provide an important insight of the soundscape features in a glacier fjord and on the behaviour of these enigmatic Arctic creatures.

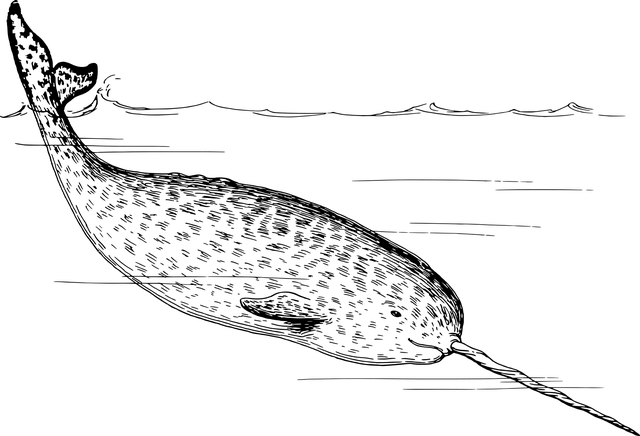

Narwhals, also known as the “unicorns of the sea”, are a medium-sized member of the family of toothed whales and can be found in the Arctic waters of Greenland, Canada, Norway, and Russia. Their most iconic feature is a long, prominent and spiral tusk, which can reach a length of up to 3 meters in males. In the Inuit folklore, the tusk is believed to be the long, twisted and braided hair of a woman, who was tossed by her blind son to a white whale and then she transformed into a narwhal. For the marine biologists, the function of the tusk has long been a topic of speculation. Recently, biologists have suggested that the tusk could be a sensory organ that senses changes in external environmental factors such as salinity, temperature and pressure.

The skittish nature of narwhals and the difficulty in observing them in polar waters makes it difficult for the scientists to approach and study them. For this reason, they are considered still an understudied cetacean. However, the Inuit have developed a deep knowledge of these animals, and have learned how to get close without disturbing them. The Inuit community is strongly intertwined with its surrounding marine ecosystems and the hunting of narwhals in particular is a profound part of their cultural tradition.

In July 2019, the scientists joined a group of Inuit hunters to search for narwhals in the Bowdoin Fjord located in Greenland. To capture the vocalizations and other environmental acoustic sources, they attached two hydrophones, or underwater microphones, on a small-motorized boat. The researchers were able to take hydroacoustic measurements from a very close distance - approximately 25m of the animal!

They recorded different types of sounds made by the narwhals, including clicks and whistles (social calls between individuals), though the latter was a less frequent event. The clicks are used for echolocation, meaning that the narwhals produce these sounds in order to locate their prey. When they approach their food, the clicks become faster, like a buzz. That the scientists were able to observe the animals while recording their buzzing provides additional evidence that narwhals forage during summertime.

Beside the sounds, the researchers were surprised to find that the narwhals approached the glacier calving front much closer than they had expected (almost 1 km distance of the front!), despite being one of the noisiest places on the ocean. Apparently, the noise of iceberg tremors, and ice melting and cracking did not seem to bother the otherwise so shy animal at all.

This fascinating study not only is a baseline of the soundscape found in the narwhals’ habitat, but it also provides valuable information for the formulation of acoustic monitoring studies in these areas.

To conclude, the researchers also discuss the ethics of using a passive hydroacoustic method. On one hand, they remark that this method is non-invasive, more reliable and less stressful for the animals unlike bio logging. However, would it be ethical to use it to give information to the Inuit hunters about the presence of narwhals on one spot? The scientists argue that, if given, this could enhance the hunting effort of narwhals. One could go further and argue that this could also have an influence on the Inuit’s hunting cultural practice. These are meaningful ethical questions that must be taken into consideration when using this method and working with the Inuit community in future studies.

References:

Evgeny A. Podolskiy, Shin Sugiyama. Soundscape of a Narwhal Summering Ground in a Glacier Fjord (Inglefield Bredning, Greenland) . Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans , 2020; 125 (5) DOI: 10.1029/2020JC016116

SHARE THIS ARTICLE