Sperm Whale

(Physeter macrocephalus)

Classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Artiodactyla

Infraorder: Cetacea

Family: Physeteridae

Genus: Physeter

Species: P. macrocephalus

Get the Facts:

The sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. The sperm whale has the largest brain on Earth, more than five times heavier than a human's. It can also produce the loudest sounds of any mammal on Earth at a 230 dB. For reference, a jet engine from 30 meters away produces about 140 decibels. Some say sperm whales are so loud that their echolocation clicks are capable of killing a human within their vicinity. The sound is amplified by a fatty, wax-filled organ called the spermaceti organ that sits on top of the skull. This is also how the name sperm whale was derived.

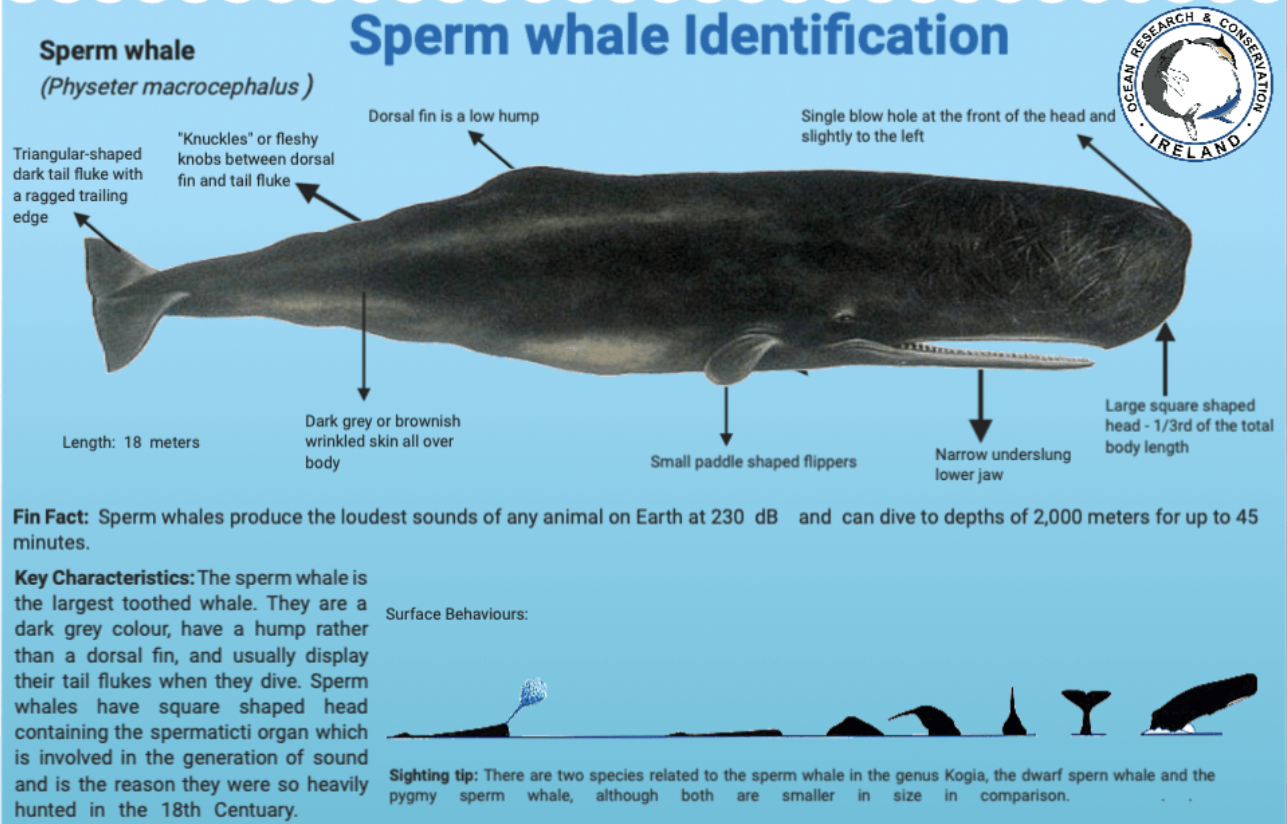

Species Identification:

Sperm whales are un-likely to be confused with another species. The blow is slanted due to the single S-shaped blowhole that is set at the front of the head and is offset to the left. The bushy blow projects up to 5 m and, because of the position of the blowhole, is directed forward and to the left. On windless days, such an angled blow is diagnostic. Sperm whales are predominantly black to brownish grey, with white areas around the mouth and often on the belly. Functional teeth (18 to 25 pairs that fit into sockets in the upper jaw) are present in the lower jaw only. The body is compressed and the head is large (one-quarter to one-third of the total length) and squarish when viewed from the side. The lower jaw is narrow and underslung. The flippers are wide and spatulate, and the flukes are broad and triangular with a nearly straight trailing edge, rounded tips, and a deep notch. There is a low rounded dorsal hump and a series of bumps, or crenulations commonly called "knuckles", on the dorsal ridge of the tail stock. The body surface tends to be wrinkled behind the head. Adult females are up to 12 m and adult males are up to 18 m in length. Weights of up to 57 t have been recorded.

Diet:

Sperm whales are known to eat giant squid, octopus, cephalopods, cuttle fish and a variety of other fish.

Behaviour:

Sperm Whales make use of echolocation for hunting prey in dark depths of oceans. They usually emit very powerful sounds from their heads during hunting and foraging. These sounds are too strong and even stun and kill prey. Sperm Whales are excellent divers. They can dive all the way down to 3,000 meters. That’s nearly 2 miles beneath the ocean surface. Bull males can stay at such depths for nearly 2 hours. That’s one of the deepest dive by any mammal species on this planet. Adult males and females can be distinguished not only by size differences, but also by the presence or absence of calluses on the dorsal hump. A large percentage of females (about 85%) have calluses, whereas males almost never have them. Fluking-up is common before a long dive and individual sperm whales can be identified by the shape and scars of their flukes.

Habitat:

Sperm whales occur in deep offshore water habitats and can be found frequently near underwater canyons, and the edges of continental shelves. In Ireland, they inhabit deep waters offshore from the west coast, in the Rockall Trough and along the Irish Atlantic Margin.

Social Structure:

Although bulls are sometimes seen singly (especially above 40° latitude), sperm whales are more often found in medium to large groups of up to fifty whales. Sperm whales are polygynous; adult males seem to employ a “searching” strategy for mating, associating with nursery groups of adult females and their offspring for only short periods of time. Sexually mature but non-breeding males that have been displaced from their maternal pods form bachelor herds. An all-male bachelor group will usually contain mails of the age 7 years to 27 years. A ‘nursery’ is a group of adult females and several immature females and immature males. Males that are older will either live in other small groups or just as single individuals.

Vocalisations:

When echolocating, the sperm whale emits a directionally focused beam of broadband clicks. Clicks are generated by forcing air through a pair of phonic lips (also known as "monkey lips" or "museau de singe") at the front end of the nose, just below the blowhole. The sound then travels backwards along the length of the nose through the spermaceti organ. Most of the sound energy is then reflected off the frontal sac at the cranium and into the melon, whose lens-like structure focuses it. The lower jaw is the primary reception path for the echoes. A continuous fat-filled canal transmits received sounds to the inner ear. The source of the air forced through the phonic lips is the right nasal passage. While the left nasal passage opens to the blow hole, the right nasal passage has evolved to supply air to the phonic lips. Low-frequency, stereotyped, clicked vocalisations, some of which are termed “codas,” are apparently distinct to individual sperm whales and may act as acoustic signatures. Some clicks are also probably used in echolocation. A creak is a rapid series of high-frequency clicks that sounds somewhat like a creaky door hinge. It is typically used when homing in on prey. A coda is a short pattern of 3 to 20 clicks that is used in social situations. Geographically separate pods exhibit distinct dialects. Large males are generally solitary and rarely produce codas. In breeding grounds, codas are almost entirely produced by adult females. Slow clicks are heard only in the presence of males. Males make a lot of slow clicks in breeding grounds (74% of the time), both near the surface and at depth, which suggests they are primarily mating signals.

Reproduction:

Sperm whales are a prime example of a species that has been K-selected, meaning their reproductive strategy is associated with stable environmental conditions and comprises a low birth rate, significant parental aid to offspring, slow maturation, and high longevity. Females become fertile at around 9 years of age. The oldest pregnant female ever recorded was 41 years old. Gestation requires 14 to 16 months, producing a single calf. Sexually mature females give birth once every 4 to 20 years. Most births occur in summer and autumn. Newborn sperm whales are 3.5 to 4.5 m in length. Lactation typically lasts for 19 to 42 months. Like that of other whales, the sperm whale's milk has a higher fat content than that of terrestrial mammals: about 36%, compared to 4% in cow milk. Males become sexually mature at 18 years. Upon reaching sexual maturity, males move to higher latitudes, where the water is colder and feeding is more productive. Females remain at lower latitudes.[9] Males reach their full size at about age 50.When breeding, the males will battle each other, and the dominant animal will mate with multiple females.

Lifespan:

Sperm whales can live 70 years or more.

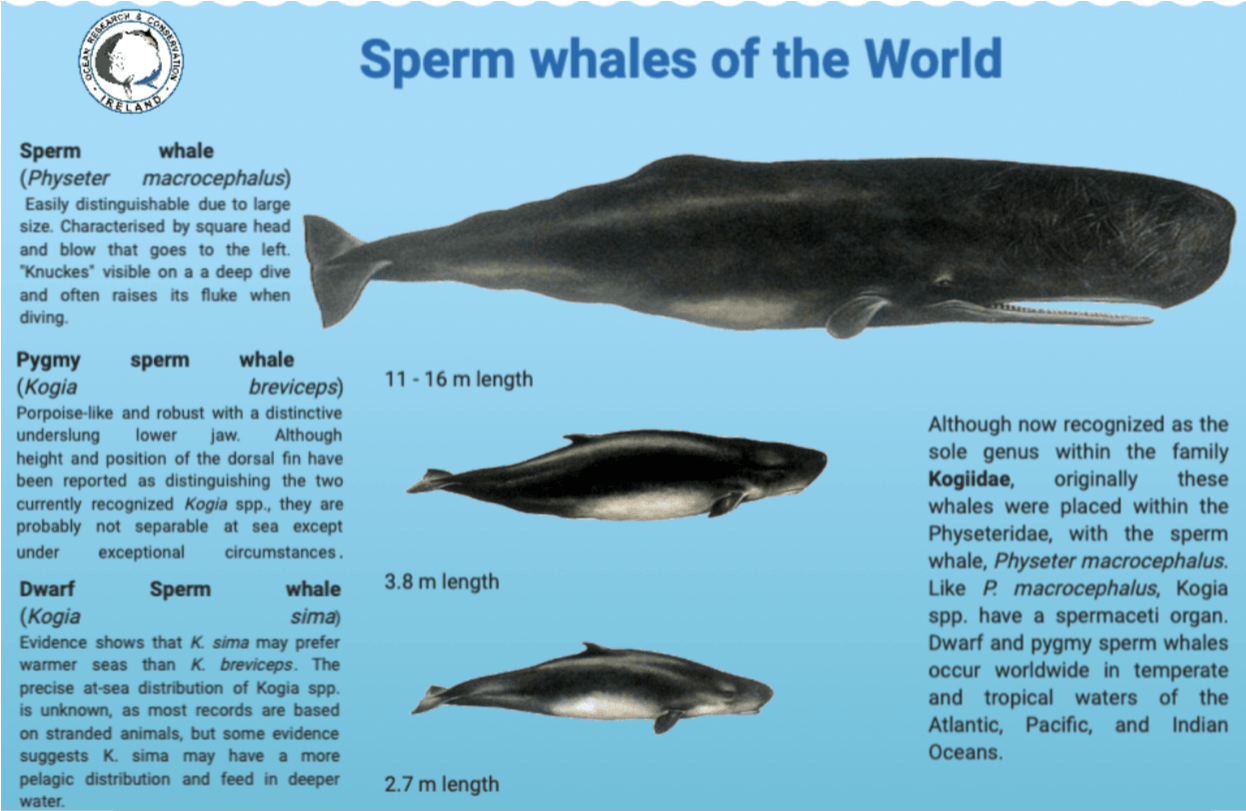

Sperm whales of the world:

The Sperm whale is the sole extant species of its genus, Physeter, in the family Physeteridae. Two species of the related extant genus Kogia, the pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps

and the dwarf sperm whale K. sima, are placed in the family Kogiidae. In some taxonomic schemes the families Kogiidae and Physeteridae are combined as the superfamily Physeteroidea.

Pygmy sperm whales are found throughout the tropical and temperate waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and occasionally among colder waters such as in waters off Russia. Pygmy sperm whale are not often sighted at sea, and most of what is known about them comes from the examination of stranded specimens. They are believed to prefer off-shore waters, and are most frequently sighted in waters ranging from 400 to 1,000 m in depth, especially where upwelling water produces local concentrations of zooplankton and animal prey.

The dwarf sperm whale inhabits temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, in particular continental shelves and slopes.is a suction feeder that mainly eats squid, and does this in small pods of typically 1 to 4 members. It is preyed upon by the killer whale (Orcinus orca) and large sharks such as the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharius).

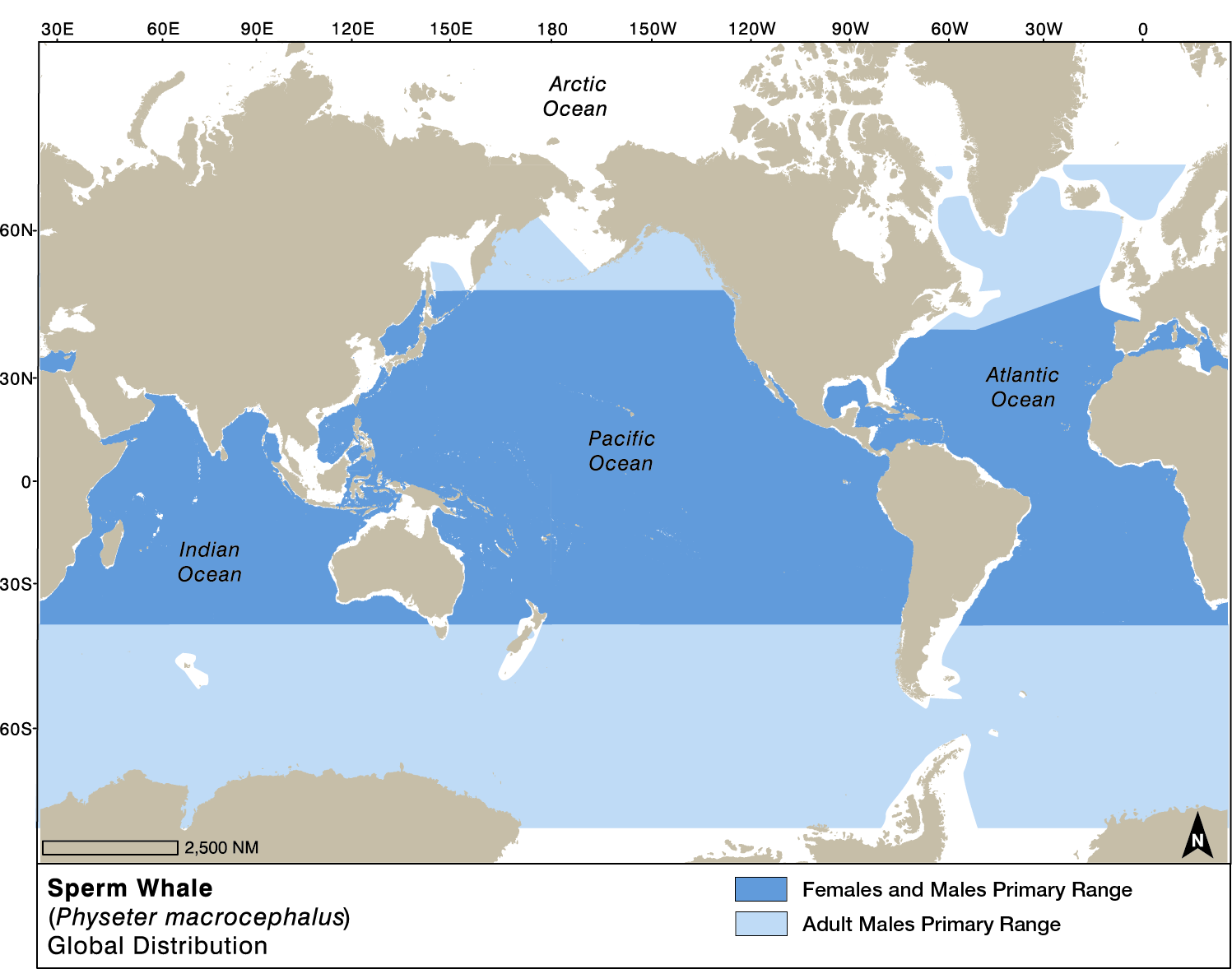

Global Distribution:

Sperm whales are globally distributed, although their distribution is dependent on their food source and suitable conditions for breeding, and varies with the sex and age composition of the group. Only adult males occur in the polar regions. Sperm whale migrations are not as predictable or well understood as migrations of most baleen whales. In some mid-latitudes, sperm whales seem to generally migrate north and south depending on the seasons, moving toward the poles in the summer. However, in tropical and temperate areas, there appears to be no obvious seasonal migration.

Population Status:

Currently, there is no exact estimates of the total abundance of sperm whales worldwide. The best estimate of the number of sperm whales worldwide is between 300,000 and 450,000 individuals. Sperm whales are listed as "Vulnerable" on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Conservation Threats:

Threats to sperm whales include vessel strike, entanglement in fishing gear, noise pollution, marine debris, plastic pollution, climate change and chemical pollutants. Sperm whales are particularly susceptible to vessel strike as they spend long periods, typically up to 10 min “rafting” at the surface between deep dives. Accidental vessel strikes can injure or kill sperm whales, although few vessel strikes to sperm whales have been documented. However, vessel traffic worldwide is increasing, which increases the risk of collisions. Sperm whales have been well documented depredating i.e. removing fish from longline gear. Sperm whales can also become entangled in many different types of fishing gear, including trap lines, pots, and gillnets. Once entangled, they may swim for long distances dragging attached gear, potentially resulting in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury. These conditions can lead to reduced reproductive success and death. Underwater noise pollution can interrupt the normal behaviour of sperm whales, which rely on sound to communicate, hunt and navigate. As ocean noise increases from human sources, communication space decreases—this masks whale calls and can drive them out of important habitats. Exploration from oil and gas, pile driving and other offshore construction can also permanently or temporarily damage their hearing and lead to death. Sperm whales can ingest marine debris, as do many marine animals. Debris such as plastic bags in the deep scattering layer where sperm whales feed could be mistaken for prey and incidentally ingested, leading to possible injury or death.