Humpback Whale

(Megaptera novaeangliae)

Humpback whale photographed on-board Baltimore Wildlife Tours, West Cork. Source: Emer Keaveney/O.R.C.Ireland.

Next Species ----->

<----- Previous Species

Classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Artiodactyla

Infraorder: Cetacea

Family: Balaenopteridae

Genus: Megaptera

Species: M. novaeangliae

Gray, 1846

Get the Facts:

Humpback whales are one of the larger rorquals and range in size from 12 up to 18 meters in length. They are called humpback after the way they raise and bend their back on a dive, accentuating the hump in-front of the dorsal fin. Humpbacks are one of the most charismatic whale species and exhibit a variety of surface behaviours. Humpback whales have the longest migration of any animal on Earth and can travel up to 8,000 km.

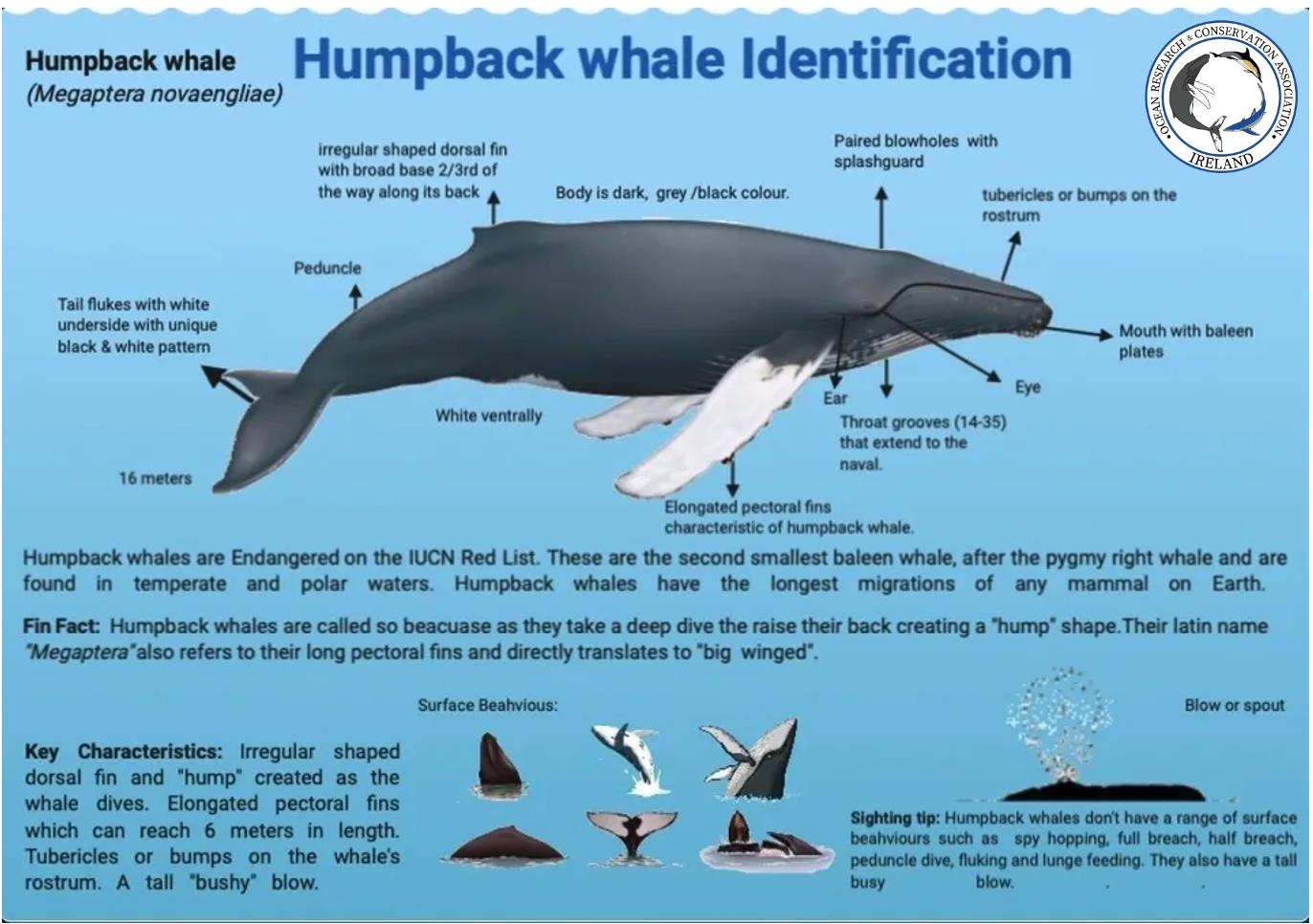

Species Identification:

The humpback whale differs greatly from the general rorqual body shape. The humpbacks body is more robust and the flippers are extremely long (up to one-third of the body length) with a series of bumps, including 2 more prominent ones in consistent positions on the leading edge, more-or-less dividing the margin into thirds. The flippers are white on the ventral side and vary from all-white to mostly black on the dorsal surface. The ventral side of the flukes also varies from all-black to all-white. The body is black or dark grey dorsally and may be white ventrally, but the borderline between dark and light is highly variable and seems to differ by population (the white extends up onto the sides and back in some Southern Hemisphere humpbacks). The flukes have a concave, with a serrated trailing edge. A humpbacks dorsal fin is irregularly shaped, low and broad-based (usually sitting on a hump). The head has a single median ridge, and the anterior portion of the head is covered with many bumps called tubericles (each containing a single sensory hair). There are 270 to 400 black to olive baleen plates, and 14 to 35 ventral pleats extending back to the navel or beyond. The blow is rather low and bushy for a balaenopterid, reaching only 3 m. It may sometimes appear V-shaped.

Similar species: At close range, the humpback is one of the easiest whales to identify. At a distance, however, there can be some confusion with other large whales, especially blue, fin and sperm whales. When a closer look is obtained, humpbacks are generally unmistakable.

Diet:

Adult humpback whales are known to consume a number of different small prey such as squid, krill, herring, pollock, haddock, mackerel, capelin, salmon and various other fish such as sand-eels. Calve consume their mothers milk, which they suckle from their mothers mammary glands until they reach a point where they are able to hunt for food and survive on their own. The thick paste like milk they receive from their mother is packed full of fat and various nutrients to allow the baby humpback to grow into a healthy adult and provides the baby whale with nutrition until it can get its food from other sources such as fish, squid and krill.

Habitat:

Humpbacks feed and breed in coastal waters, often near human population centres, and this helps make them one of the most familiar of the large whales. They migrate from tropics (breeding areas) to polar or sub-polar regions, reaching the ice edges in both hemispheres (feeding areas); their migrations take them through oceanic zones and they can travel up to 6,000 km during their migration. Humpback whales can also be associated with waters over continental shelves when migrating between their mid/polar summer feeding grounds and the warm, tropical waters (especially near islands and reef systems) of their winter breeding grounds. In Irish waters humpback whales are generally found offshore, although can also sometimes be viewed from the coast. Sightings of humpback whales are most frequent along the west and south coast of Ireland, although they have been observed along the North coast, from Donegal Bay to off the Antrim coast.

Behaviour:

Humpbacks are probably the most acrobatic of all great whales, sometimes performing full breaches that bring their entire body out of the water. They are adaptable lunge feeders, which use coordinated such as bubble nets, bubble clouds, tail flicks, and other techniques to help concentrate krill and small schooling fish for easier feeding. Bubble netting is a group activity that can involve up to several dozen humpback whales. One group of whales will swim below a large group of fish and form a circle which they use to herd the fish together. The group then begins blowing bubbles to enclose and shrink the circle of fish and compact the fish into a tight herd. Some whales may also dive deeper and force the fish upwards where they become trapped in the bubble net. Once they’ve herded the fish together they can then take turns swimming through the herd consuming as many fish as possible using a filter feeding method. Filter feeding involves a baleen whale swimming towards a group of fish or krill with its mouth open. The baleen bristles in their mouth act as a filter by trapping the prey in the bristles while allowing water to filter through. After gathering a large group of fish or krill in its mouth the whale pushes the excess water out its mouth with its tongue while keeping the prey trapped inside its baleen bristles. Once the water is expelled the whale can then swallow its food whole.Sometimes humpbacks gather into coordinated groups of up to 20 or more whales, which work together to herd and capture prey. Although humpback whales can consume large quantities of food they are known to fast for large portions of time during the autumn/winter and will live primarily off of the fat they stored from the food they’ve eaten during the summer months. When the winter season rolls around humpback whales are primarily focused on mating and spend very little time hunting or foraging for food. In fact for many species such as the humpback whale the autumn/winter time is known as their mating season. During mating season these marine mammals spend several months traveling to their mating grounds, performing mating rituals, giving birth and socialising.

Humpback whales often raise their flukes when they dive and can stay submerged for 15- 20 minutes, although 10 minutes is more common. Individual humpback whales can be identified using photographs of the distinctive markings on the undersides of their flukes, similar to a humans fingerprint. Such photos can be of great help in defining movements and migrations of this and other species.

Social Structure:

Although they generally occur singly or in groups of 2 or 3, larger aggregations develop in feeding and breeding areas. Sometimes humpbacks gather into coordinated groups of up to 20 or more whales, which work together to herd and capture prey. Mothers travel with their offspring for the first year of the calf's life. However, beyond the presence of mother-calf/yearling pairs, no obvious relatedness pattern have been found among whales sampled either in the same pod or on the same day. If any social organisation does exist, it is formed transiently when needed rather than being a constant feature of the population, and hence is more likely based on reciprocal altruism than kin selection.

Vocalisations:

Humpback whales produce a series of beautiful and varied sounds for a period of 7 to 30 minutes and then repeat the same series with considerable precision, these are known as themes. We call such a performance "singing" and each repeated series of sounds a "song." Each individual adheres to its own song type. Only the males sing and all male humpbacks in the same region sing the same song. The song itself changes over time, making it different from year to year. The songs generally occur during the breeding season, suggesting that they are related to breeding. There seem to be several song types around which whales construct their songs, but individual variations are pronounced. Songs are repeated without any obvious pause between them; thus song sessions may continue for several hours. The sequence of themes in successive songs by the same individual is the same. Although the number of phrases per theme varies, and new phrases may be added over time, no theme is ever completely omitted.

Humpback whales produce moans, grunts, blasts

and shrieks. Each part of their song is made up of sound waves. Some of these sound waves are high frequency. Whales also emit low frequency sound waves. These sound waves can travel very far in water without losing energy. Researchers believe that some of these low frequency sounds can travel more than 10,000 miles in some levels of the ocean! The range of frequencies that whales use are from 30 Hertz (Hz) to about 8,000 Hz, (8 kHZ). Humans can only hear part of the whales' songs. We aren't able to hear the lowest of the whale frequencies. Humans hear low frequency sounds starting at about 100 Hz. Non-song sounds produced by humpback whales include those associated with foraging activities. Peak frequencies of feeding calls in the Northwest Atlantic were generally less than 1 kHz, but ranged as high as 6 kHz, and sounds were generally less than 1 second in duration.

Reproduction:

Humpback whales reach sexual maturity at 6-10 years of age or when males reach the length of 11.6 m and females reach 12 m. Due to their migration patterns, reproduction is strongly seasonal, with peaks of spermatogenesis and ovulation occurring during the winter. The primary function of migration is believed to be as a reproductive display to attract potential mates. Once humpback whales have arrived at the winter breeding areas, intense competition begins between the males. Due to the lack of food availability on the winter grounds, energy constraints faced by males force them to compete over females with high reproductive potential rather than females that are less likely to bear a calf the following year. The most commonly observed aggressive behaviour is the head lunge, during which a whale thrusts its head forwards out of the water, often with the throat area inflated. In some cases, forceful contact occurs between competing males, resulting in bloody wounds. The primary reason behind male competition on the breeding grounds is that humpback whales practice polygyny. Humpback whales do not form stable pair bonds during the winter breeding season. Females are seen with multiple males and males are seen with multiple females throughout each breeding season, forcing males to compete for the most fertile females. On the breeding grounds, male humpback whales also appear to compete for access to estrus females using their now well-known complex songs as part of their breeding display, sometimes followed by a heat run, where one or more males will pursue a female. Calves are born on wintering grounds in tropical and subtropical regions and can weigh 2,000 lb. Each female typically bears a calf every 2-3 years. Females have a gestation period of 11-12 months, and the calf will remain with its mother for 6-10 months.

Lifespan:

The life expectancy of humpback whales is an estimated 45 to 50 years, although research has suggested that many can live upwards of 90 years or more.

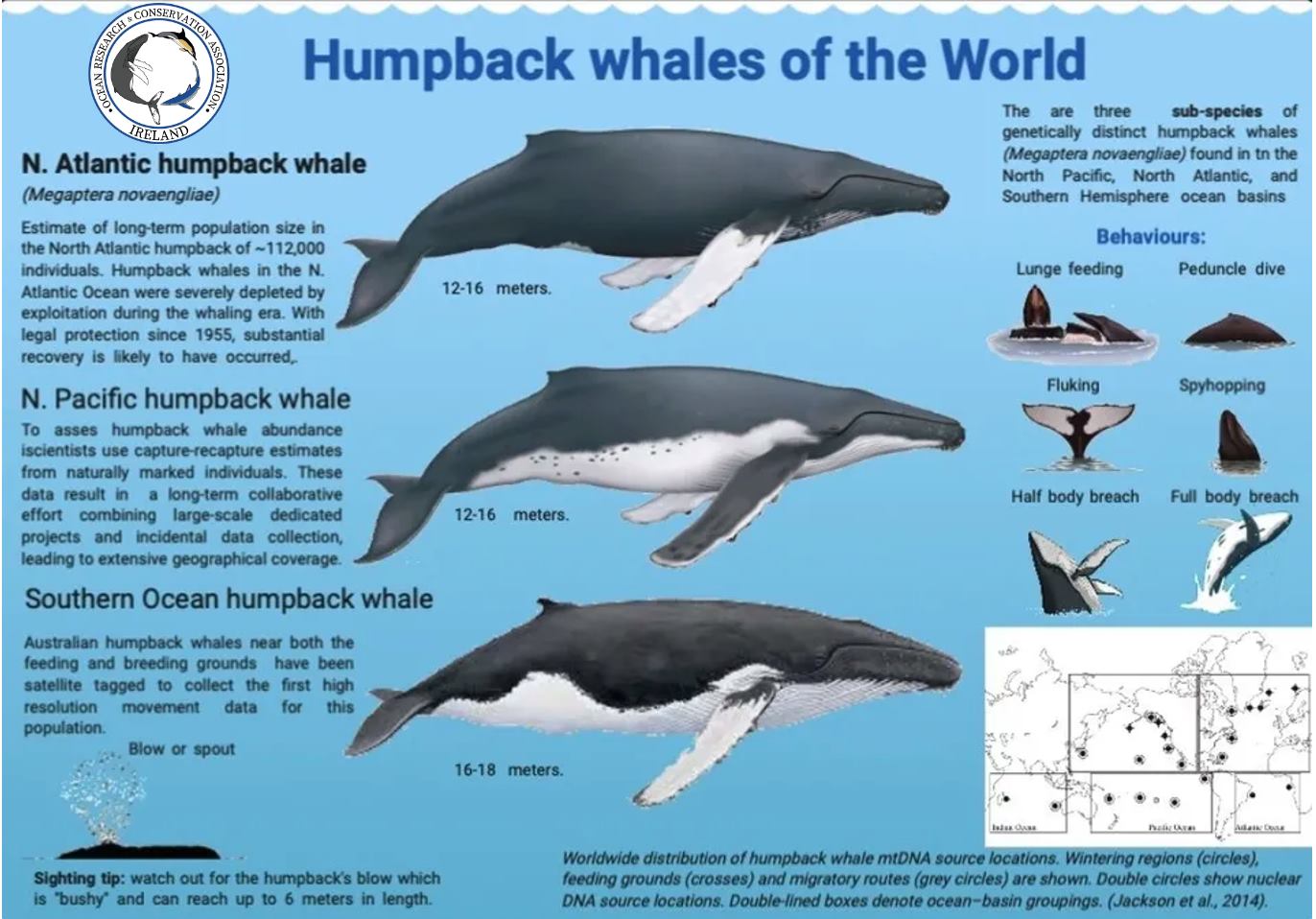

Humpback whales of the World:

Three separate subspecies of humpback whales have been identified from genetic studies in the North Pacific, North Atlantic and the Southern Hemisphere. Though these expert swimmers make the longest migrations of any mammal, the subpopulations in the different oceans stick to separate routes. This isolation may explain why the northern swimmers tend to have darker colouring on their underbellies and tails than their southern counterparts. Indicating that the different populations are evolving independently.

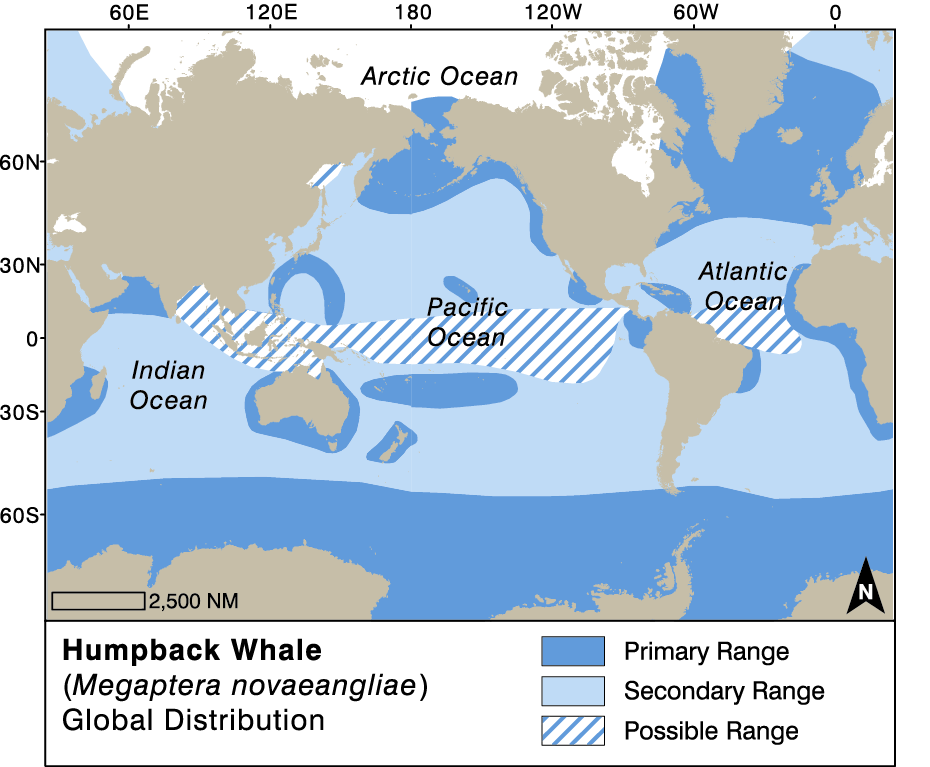

Global Distribution:

Humpback whales occur worldwide in all major oceans. While they generally demonstrate a preference for continental shelf areas, they are also known to cross deep offshore waters, and spend time over and around seamounts in the open ocean. Every known population of humpback whales, with the exception of the Endangered Arabian Sea population, performs long seasonal migrations; spending summers feeding in cold productive waters at high latitudes and winters on tropical breeding grounds where they mate, calve, and nurse their young. Some individuals travel as far as 8,000km between their breeding and feeding grounds8. Southern Hemisphere populations generally feed around the Antarctic between November and March, and migrate toward breeding grounds near the equator where they mate and give birth between July and October1. Northern Hemisphere populations do the opposite, feeding at high latitudes off the continents of North America and Europe between June and October, and mating and calving at low latitudes in the Caribbean, West Pacific and West Atlantic between December and March or April

Humpback whale global distribution. Adapted by Nina Lisowski from Jefferson, T.A., Webber, M.A. and Pitman, R.L. (2015). “Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification,” 2nd ed. Elsevier, San Diego, CA. Copyright Elsevier: http://www.elsevier.com

Population Status:

All the new assessments of humpback whale stocks conducted by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) Scientific Committee to date indicate that the stocks concerned have recovered to levels at or above their post whaling era level circa 1940.

Conservation Threats:

Humpback whales in Irish waters face a number of conservation threats. Entanglement in static set fishing gear, such as vertical lines leading to the seabed from lobster pot fishing poses a huge risk but is under-reported in Ireland. Abandoned fishing gear may become wrapped around a humpback whale, causing injury to its flesh (leaving it open to parasites and infections), and the whale may drag this gear for several hundreds of miles before becoming exhausted and eventually drowning. Other threats include ship strike, where a humpback can be injured or killed. However, this is also under-reported in Irish waters. Noise pollution from offshore oil and gas exploration, and pile driving for offshore wind farms can also cause disturbance, if not direct injury or even death. Often noise pollution can mask their vocalisations or move them away from important feeding areas. Plastic pollution is also a threat to humpback whales that visit Irish waters.