KEEP THE NOISE DOWN!

Sophie A. Maycock | 14th of December 2020.

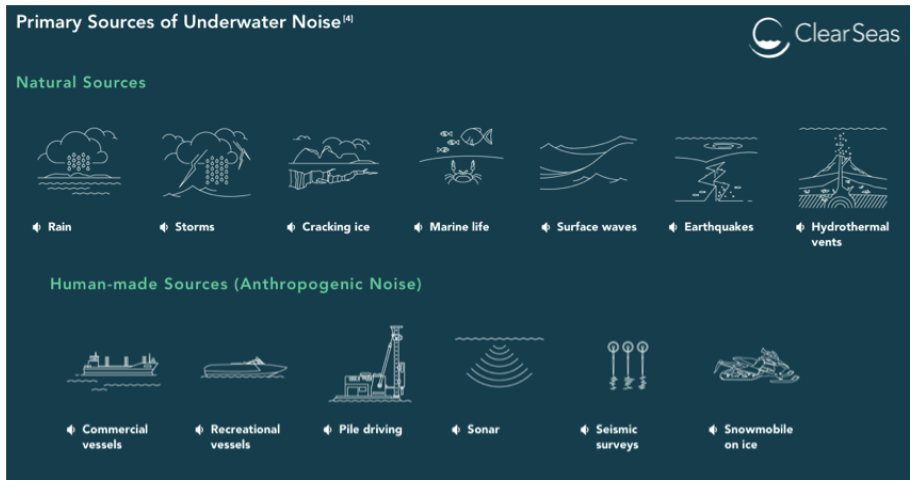

In recent years scientists have become increasingly concerned that the impact that human beings have on the natural world might be more extensive and insidious than previously thought. We have seen how litter, plastic pollution and oil spills can have rapid impacts on marine life, and we are starting to understand that climate change could seriously affect our oceans in the long-term… but there is also another form of disturbance that scientists are becoming aware of; “noise pollution”. Noise pollution refers to the plethora of sounds which are pumped into marine environments by human activity. You might think this does not sound like a serious issue, but, in fact, when you consider underwater drilling, shipping lanes, sonar, the use of explosives, seismic surveys, blast fishing… you start to realise that we expose marine life to an enormous amount of unnatural sound (known as “anthropogenic sound”). There has been a lot of attention on this issue in recent years, after several mass stranding of whales and dolphins were linked to noise pollution. But what about other animals? Is noise pollution really damaging to fish like sharks?

Noise pollution can be seriously damaging to many different species of marine wildlife. At the lowest level, extensive background noise from boat motors or offshore wind farms, even at relatively low volumes, can cause increased stress to marine life or mask their sounds which are critical for their survival. Research has shown that noise pollution alters the behaviour of bony fish; changing how they feed, socialise, avoid predators and move around their habitat.

Louder noises, such as those from underwater explosions, can even cause temporary or permanent deafness. In the case of “cetaceans” (whales, dolphins and porpoise) it is thought that noise pollution can be especially damaging because these animals use sound to communicate, navigate and hunt prey, like fish and squid. We now know that anthropogenic sound can alter how often whales vocalise, the patterns of their movement and how they forage for food. There is an increasing body of scientific literature about how noise pollution affects cetaceans (Bravo, scientists!), but work on other animals, like sharks, is more scarce (Chapuis

et al , 2018).

It might surprise you to learn that sharks can hear! But it’s true. In fact, they have a very well-developed sense of hearing and are able to detect sounds from several kilometres away. Some species of sharks even use sound to communicate; using “tail slaps” on the surface of the water to compete for food resources.

The bodies of sharks are equal in density to the surrounding water. Therefore, sound waves travel throughout their entire body, until they come into contact with a structure which is more or less dense. This is known as being “acoustically transparent”. In sharks, the sound waves coming into contact with a dense organ known as the “otoconia”, causes delicate sensory cells (known as “cilia”) to be moved, which is interpreted by the brain as sound detection (Casper

et al , 2012). It is thought that sharks can perceive sounds with a frequency between 20 Hz and 1.5 kHz, depending on the species. They are especially sensitive to low-frequency sounds, with a peak in perception between 200 and 600 Hz (Casper

et al, 2012 & Chapuis

et al, 2018).

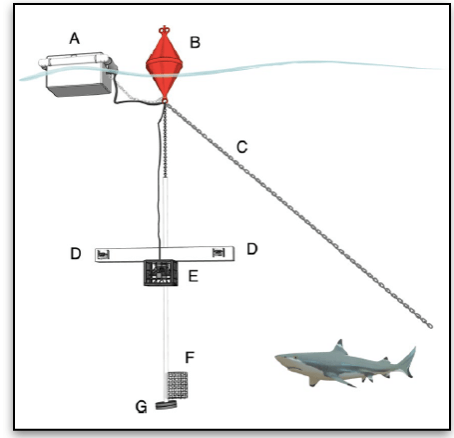

To understand how noise pollution might affect sharks, a research team baited sharks towards their boat and tested how they behaved when they played them different sounds through an underwater microphone. They compared the reaction to artificial sounds of mixed frequencies and intensities, against the calls of orca (

Orcinus orca ), which are experienced naturally in the marine environment. In Western Australia, they tested seven different species: sicklefin lemon sharks (

Negaprion acutidens ), bronze whalers (

Carcharhinus brachyurus ), grey reef sharks (

C. amblyrhynchos ), dusky sharks (

C. obscurus ), sandbar sharks (

C. plumbeus ), scalloped hammerheads (

Sphyrna lewini ) and zebra sharks (

Stegostoma fasciatum ), and they additionally tested great white sharks (

Carcharodon carcharias ) with the same experimental set-up in South Africa (Chapuis et al, 2018). The Australian species were all coastal and/or reef dwelling, whereas great whites are nomadic and wide-ranging.

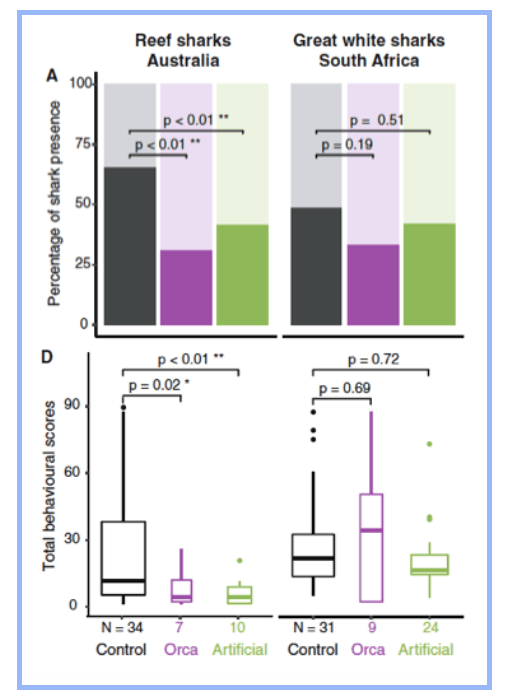

The scientists discovered that all the coastal sharks approached the bait much less often when both different sounds were played to them, compared to “control” conditions (when no sounds were played). They recorded significantly fewer inquisitive interactions when sounds were being played and the sharks did not make attempts to bite the bait. Whats more, when playing the artificial sounds, the sharks were much slower to arrive at the food source. The great whites also arrived late and left quickly when artificial sounds were being played. Basically, despite being tempted in with tasty baits, the sharks were still deterred by unnatural noises. These findings confirm that underwater sounds do alter shark behaviour across many different species, but that the responses can vary between species (Chapuis

et al, 2018).

“Certain underwater sounds can alter the behaviour of some sharks

and potentially deter them from entering an area and/or interacting with a potential food source”-

Capuis

et al,

2018

In the natural environment, continuous rhythmic sounds, like wind, waves, bubbles, the flow of schooling fish and the calls of other animals fall within the low-frequency range perceptible to sharks. These sounds are a part of their natural “soundscape” and so do not elicit a startle response. However, anthropogenic sounds are often chaotic and lacking rhythm, with quick variations in intensity and frequency. The researchers hypothesised that these unfamiliar sounds likely acted as a “cue”, which triggered sharks to exhibit “aversion behaviours”. This tells us that anthropogenic noise might repel sharks from food-rich habitats. In the long-run, this could shift their natural ranges and seriously impact upon their health (Chapuis

et al, 2018).

Realistically, anthropogenic noise pollution is not going to stop any time soon - international shipping, drilling for oil and military exercises are all seriously big business. Therefore, the only weapon that we have to fight it will be to perform more scientific research into the effects of noise pollution. If we are able to determine that specific anthropogenic sounds adversely affect marine life, then we can petition parliaments to control these activities in some way.

“Given the combination of the worldwide increase in anthropogenic aquatic noise as well as the drastic population decline in many species of sharks,

it is imperative that studies be conducted to

determine whether these fishes are being further threatened by our noise pollution”

-

Casper

et al, 2012

If you would like to learn more about how noise pollution is affecting marine life and how you might be able to help, visit our website and become a member to support our

Smart Whale Sounds Project!

References

Casper BM, Halvorsen MB & Popper AN (

2012 )

. Are sharks even bothered by a noisy environment?

Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology , 730.

Chapuis L, Collin SP, Yopak KE, McCauley RD, Kempster RM, Ryan LA, Schmidt C, Kerr CC, Gennari E, Egeberg CA & Hart NS

(

2018 ). The effect of underwater sounds on shark behaviour.

Scientific Reports , 9:6924.