Farmers of the Ocean: Whale poo and its role in ocean health!

Farmers of the Ocean: Whale poo and its role in ocean health.

EMER KEAVENEY | 26th September 2019.

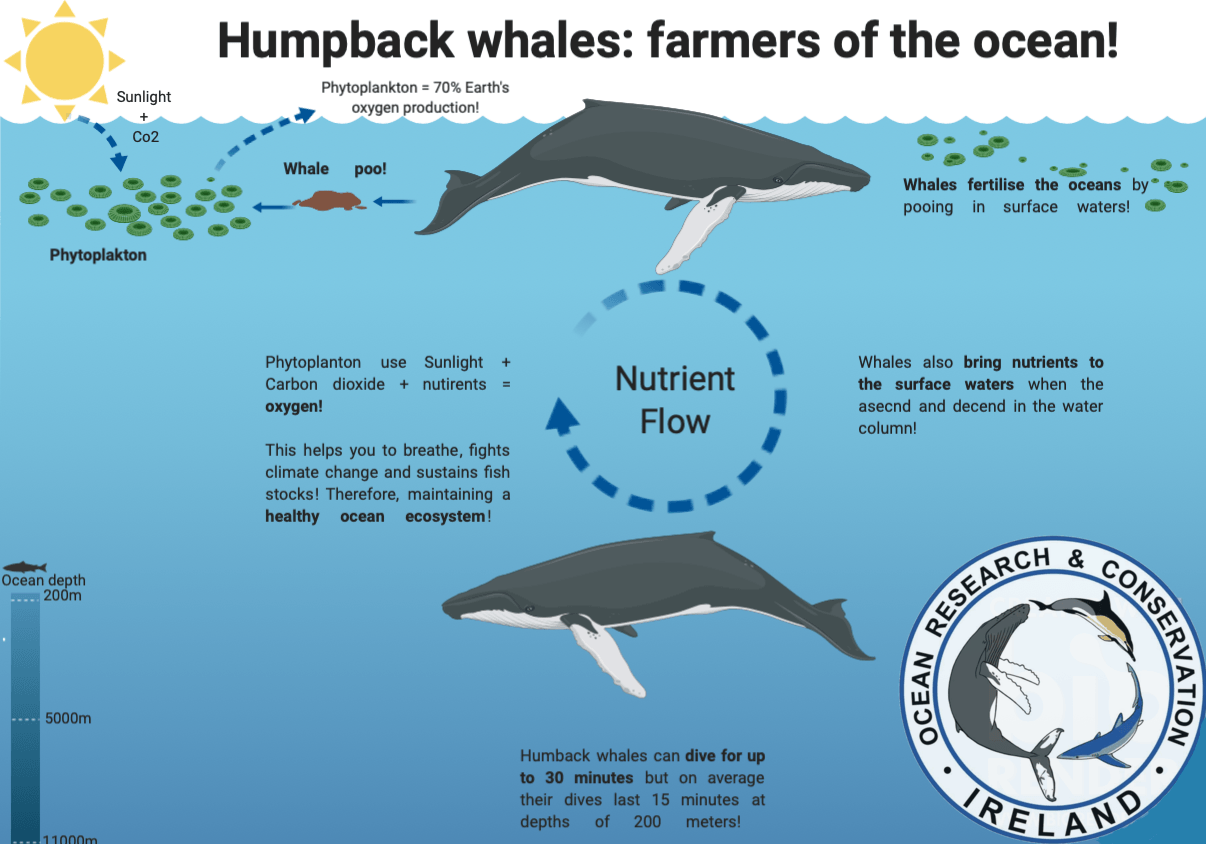

Whale regulate climate and marine ecosystem functions through their migration patterns and deep diving behaviour, which promotes the circulation of nutrients through-out the water column. While many mammals produce excrement in solid clumps, whale poo has been described as a"flocculent" almost wool like substance, forming light plumes that stays near the oceans surface and directly fertilise phytoplankton, the base of the oceans food chain! Read on to find out more about how whales are in-fact farmers of the ocean!

The idea that

whale poo could help to

fertilise the ocean has been floating around for a while! Whales are known to feed on forage fish such as herring, sprat and krill, but because these gentle giants form blubber and not muscle, they have little use for the iron in their diet.

Consequently, this essential element passes straight through the digestive tract of a whale and exits the body in a plume of faecal material that acts like liquid manure. Numerous studies have shown that the growth of microscopic algae or phytoplankton is limited by the iron concentration in the seawater. For example, using trace-metal clean sampling techniques, Martin and Fitzwater (1988) added trace amounts of iron (2.5 nano-molar) to bottles containing natural phytoplankton assemblages and found marked increases in biomass through time.

Iron enters the ocean either through wind-blown dust or through the upwelling of water from the ocean depths. The deep water is richer in nutrients because particulate matter, including dead algae and detritus, sink out of the sunlit layer to the ocean’s interior, where microbial processes break it down into its constituent chemicals. Any process that keeps the nutrients in circulation in the surface layer, rather than sinking, should ensure that algal growth is sustained. This is where the notion of whales as fertilisers of the ocean comes in.

Blue Whale Scat. Credit: Jason Isley Getty Images

Just how important a whales role is in recycling iron could only be determined by measuring the amount of iron in their faeces. However, the difficulty of measuring the iron content of whale poo has only been overcome in recent years. As part of the non-lethal whale research program being conducted by the

Australian Marine Mammal Centre at the Australian Antarctic Division, scientists using advanced molecular techniques to examine whale poo collected from around the world in a bid to to understand their diet, looked at the role of iron in ocean productivity using sophostpcated equipment required to measure the minute quantities of iron in seawater.

At the same time as these molecular studies were being carried out, allowing scientists to determine what the whales diet was composed of, they analysed 28 samples from four different species of whale, and discovered that baleen whale poo contained 10 million times more iron than an equivalent weight of seawater. They were also able to confirm that the krill in their diet was the source of the iron they were measuring. Finally, the researchers wanted to see how much iron whales had stored in their bodies, so they measured the concentration in muscle samples from stranded blue and fin whales, and again got very high values.

These findings suggested that the role of larger animals in the cycling of nutrients had been overlooked in the past; particularly in the Southern Ocean where iron is a limiting nutrient. Despite the fact that individual whales contain large amount of iron, their relative scarcity means that their main role seems to be in converting the iron from prey into liquid manure. This fertilising role is on a rather small scale today, in comparison to the days pre-whaling, when the abundance of great whales in the world's oceans was far greater, meaning their role in fertilising the oceans were much larger. This means that when there were more whales present in the world's oceans the productivity of our oceans was also increased resulting in a healthier and more productive marine ecosystem, actually enhancing fisheries production rather than reducing it.

References:

Nicol, S. , Bowie, A. , Jarman, S. , Lannuzel, D. , Meiners, K. M. and Van Der Merwe, P. (2010), Southern Ocean iron fertilization by baleen whales and Antarctic krill. Fish and Fisheries, 11: 203-209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00356.x

SHARE THIS ARTICLE