They came. They saw. They conquered? The basics of invasive species in Ireland.

Invasive species are often defined as those that are not native to the location they have been found in, possess the ability to spread, and typically adversely affect the local populace, habitats and bioregions they have occupied. It must be noted that invasive species are not to be confused with migratory species such as the smooth hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena) and other transient megafauna, no matter how out of place they seem. Furthermore, it can be argued whether ‘invasive’ species present as a result of climate change driven range extensions are truly invasive, or whether this is natural progression.

Despite the generally accepted definition, non-indigenous species (NIS) can have a range of both detrimental and advantageous ecological, environmental, economic and social impacts within our waters. Nevertheless, it is still important to be able to identify these species and their methods of transmission, to predict when and where instances are likely to occur, and to try and devise appropriate mitigation and management inline with guidance and legislation.

Although all invasive species can be a cause for concern, marine NIS’ are particularly problematic. This is due to the sheer size and scope of that big blue expanse, alongside all of the potential methods of dispersal and evasion associated with the marine environment. Making it difficult to control and eradicate established invasive species. Often such species are found purely by chance especially for lesser known, inconspicuous, or cryptic species which may be difficult to identify (i.e. those physically adept at hiding and those currently yet to be identified by science due to being hidden within other taxa etc.). The needle in a haystack analogy very much applies in this context, except both are underwater and the needle may or may not be able to swim or looks like hay.

All is not lost however, as established and potentially invasive species have been documented within Ireland for decades. Many of these have warranted a number of research papers, projects and initiatives to be launched in tandem with legislation. All of which aims to aid and inform industry and public awareness, engagement, monitoring and management.

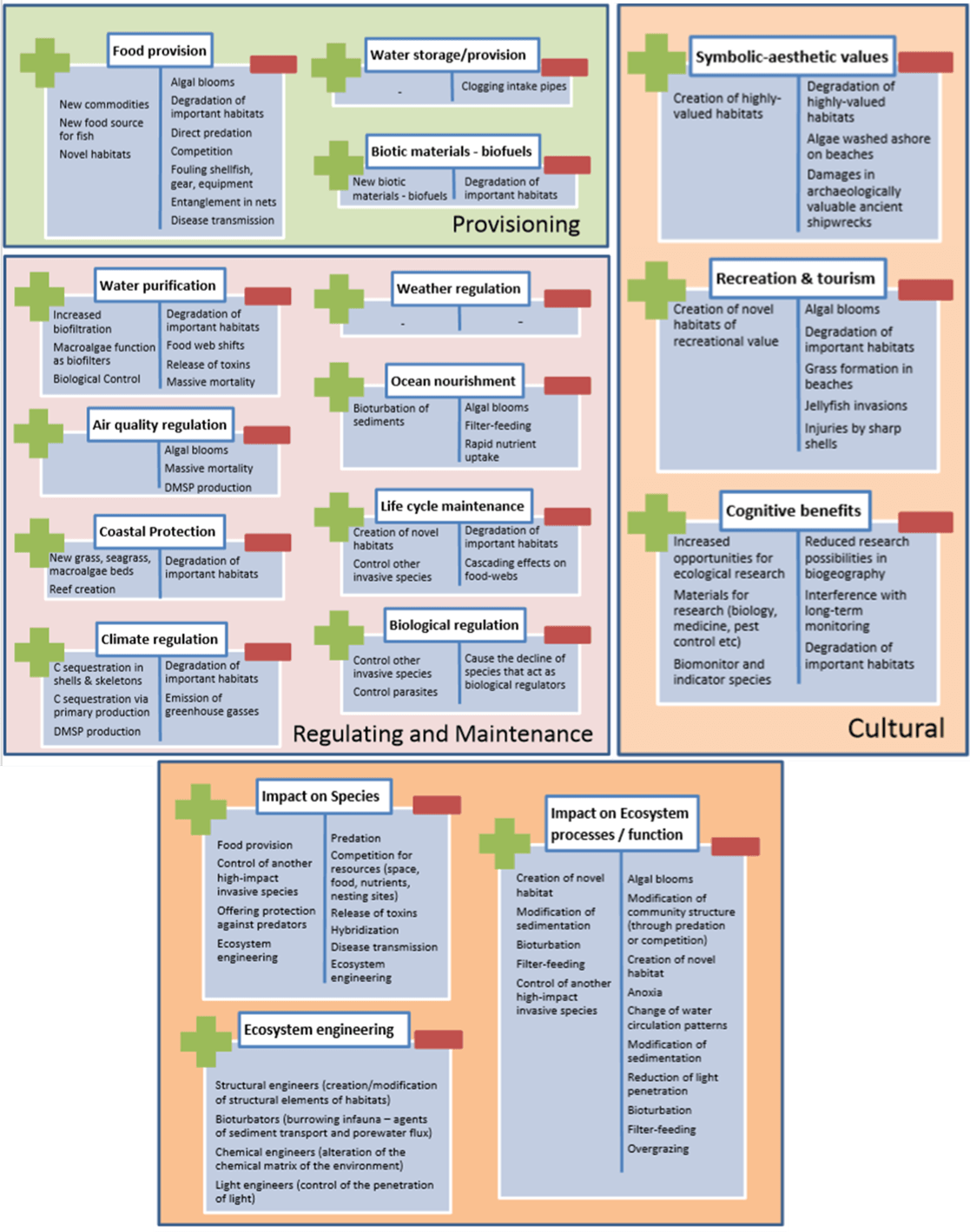

Before identifying some of these marine marauders and how they can end up on your local coastline, it is probably best to outline the impacts they can have and how they generally can be bad news. Katsanevakis (2014 ) highlighted some of the impacts invasive species can have on biodiversity and marine ecosystem services previously outlined by Liquete (2013). These can broadly be grouped as provisioning, cultural and social, regulation and maintenance, and ecological impacts, but are often interlinked. Figure 1 goes into greater depth as to the impacts associated with invasive species, but generally negative impacts such as interbreeding, outcompeting or predating upon native species and fish stock, altering habitats to the detriment of native species, spreading disease, and the ability to potentially injure humans predominate. For example, whilst invasive sea squirts (i.e. Ascidiella aspersa , Corella eumoyta ) may have potentially beneficial applications in the production of natural marine products, they have ultimately been shown to compete with farmed mussels at Killary Fjord for food and space (Palanisamy et al. , 2018). Ultimately reducing mussel yields whilst simultaneously resulting in increased maintenance costs, financially impacting the industry on multiple levels.

Now it is probably safe to say the vast majority of people are not too interested in or worried about sea squirts unless they impact them directly, after all there aren’t any films about them instilling the same sort of fear in people as their toothy neighbours, with or without the addition of extreme weather. However, there are sadly no confirmed species of invasive shark or other large predatory fish to satiate you marine masochists out there, but I can assure you the damage done by Irish NIS’ is no less horrifying… For example, the round goby ( Neogobius melanostomous ) is a salt tolerant species which can occupy both the marine and freshwater environment (euryhaline), eating its way through native and invasive species alike and leaving a trail of destruction in its wake. Other notable examples include, the rapa whelk ( Rapana venosa ), American lobster ( Homarus americanus ), blue crab ( Callinectes sapidus ), Pacific oyster ( Crassostrea gigas ), acorn barnacle ( Austrominius modestus ), orange ripple bryozoan ( Schizoporella japonica ), and Japanese wireweed ( Sargassum muticum ), for much the same reasons as any other invasive species (Allen et al. , 2006., Kraan, 2008., Gallardo and Aldridge, 2013., Loxton et al. , 2017. – figure 2).

So how are species from say Australia, Asia or the Americas getting to Ireland, and what is being done about it? The answer is simply any way they can. Be this on the surfaces of recreational or transportation vessels, on migratory species, in ballast water, within food shipments, and as a result of the exotic pet trade just to name a few confirmed invasive vectors. Tidbury (2016) used information concerning aquaculture, shipping and recreational boating to identify areas around Ireland and the rest of the British Isles most likely to be sites of invasions, testing predictions utilising established populations of the invasive carpet sea squirt ( Didemnum vexillum ). It was shown that areas most at risk included those surrounding Belfast, Cork, Derry, Dublin, Galway and Westport, largely due to aquaculture, fisheries, shipping and recreational boating being concentrated in those areas (Figure 3).

Such studies are crucial to the management of invasive species, as predicting where they are most likely to occur can focus monitoring and management efforts in order to comply with legislation. Ireland is subject to International, European, and Irish legislation concerning invasive species, which includes EU Invasive Alien Species Regulation (1143/2014) and Irelands National Biodiversity Action Plan. All in all, these state that potentially harmful invasive species are to be identified, reported, monitored, controlled, contained and or eradicated when feasible, all whilst promoting native species. Naturally the exact methods vary between species and locations, but generally involve early detection and prevention, manual control (i.e. physical removal), chemical control (i.e. pesticides), competition (i.e. reintroduce native species once NIS are removed), and biological control (i.e. introduce natural predators) in succession. However, the stages after manual control can have significant limitations and detrimental impacts within the marine environment. For example, introduced predators are potentially invasive themselves and may also consume indigenous species.

If wanting to find out more about invasive species in Ireland, ways to get involved, or projects such as the European funded ‘Mapping Irelands invasive species project (2020 – 2021)’, please visit invasivespeciesireland.com , biodiversityireland.ie , nonnativespecies.ie , or msp-platform.eu.

References:

Allen, B.M., Power, A.M., O’Riordan, R.M., Myers, A.A., and McGrath, D., (2006). INCREASES IN THE ABUNDANCE OF THE INVASIVE BARNACLE ELMINIUS MODESTUS DARWIN IN IRELAND. Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 106 (2): 155 – 161.

Gallardo, B., and Aldridge, D.C. (2013). The ‘dirty dozen’: socio-economic factors amplify the invasion potential of 12 high-risk aquatic invasive species in Great Britain and Ireland. Journal of Applied Ecology. 50: 757 – 766.

Katsanevakis, S., Wallentinus, I., Zenetos, A., Leppäkoski, E., Çinar, M.E., Oztürk, B., Grabowski, M., Golani, D., and Cardoso, A.C. (2014). Impacts of invasive alien marine species on ecosystem services and biodiversity: a pan-European review. Aquatic Invasions. 9 (4): 391 – 423.

Kraan, S. (2008). Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt in Ireland: an invasive species on the move. Journal of Applied Phycology. 20: 823 – 832.

Liquete, C., Piroddi, C., Drakou, E.G., Gurney, L., Katsanevakis, S., Charef, A., and Egoh, B. (2013). Current status and future prospects for the assessment of marine and coastal ecosystem services: a systematic review. PLoS ONE . 8(7): 1 – 15.

Loxton, J., Wood, C.A., Bishop, J.D.D., Porter, J.S., Spencer Jones, M., and Nall, C.R. (2017). Distribution of the invasive bryozoan Schizoporella japonica in Great Britain and Ireland and a review of its European distribution. Biological Invasions. 19: 2225 – 2235.

Palanisamy, S.K., Thomas, O.P., and McCormack, G.P. (2018). Bio-invasive Ascidians in Ireland: A Threat for the Shellfish Industry but Also a Source of High Added Value Products. Bioengineered . 9 (1): 55 – 60.

Tidbury, H.J., Taylor, N.G.H., Copp, G.H., Garnacho, E., and Stebbing, P.D. (2016). Predicting and mapping the risk of introduction of marine non-indigenous species into Great Britain and Ireland. Biological Invasions. 18: 3277 – 3292.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE