The Use of Pingers in the Conservation of the Harbour Porpoise.

One of the greatest global threats facing marine mammals is entanglement in fishing nets. Across the world, cetaceans are vulnerable to by-catch mortality, which is defined as the “capture of unwanted, unmanaged or discarded catch. Marine mammals show delays in reaching sexual maturity and have low rates or reproduction. These life history traits make them especially vulnerable to bycatch mortality.

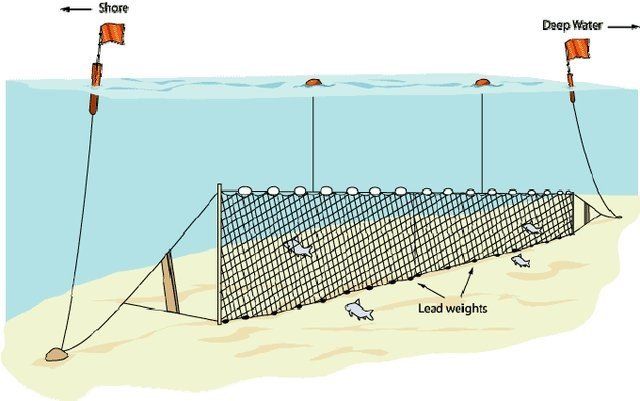

Small-scale fisheries can have significant levels of incidental catch. These fisheries can often lack defined management structures and enforcement mechanisms, making it harder to over-see and enforce correct conservation strategies. In particular, gill net fisheries are regarded as one of the largest causes to bycatch mortality in cetaceans. A gill net is a type of netting deployed in vessels that hang into the water column to trap fish. However, more often than not, these structures can capture unintended victims.

Research has shown that porpoises are especially vulnerable to being captured in gillnets. In fact, all six species of porpoise’s experience problems with gillnet fisheries. It is believed that this is due to their tendency to occupy areas near shore, where most of the fishing takes place (Jefferson and Curry, 1994).

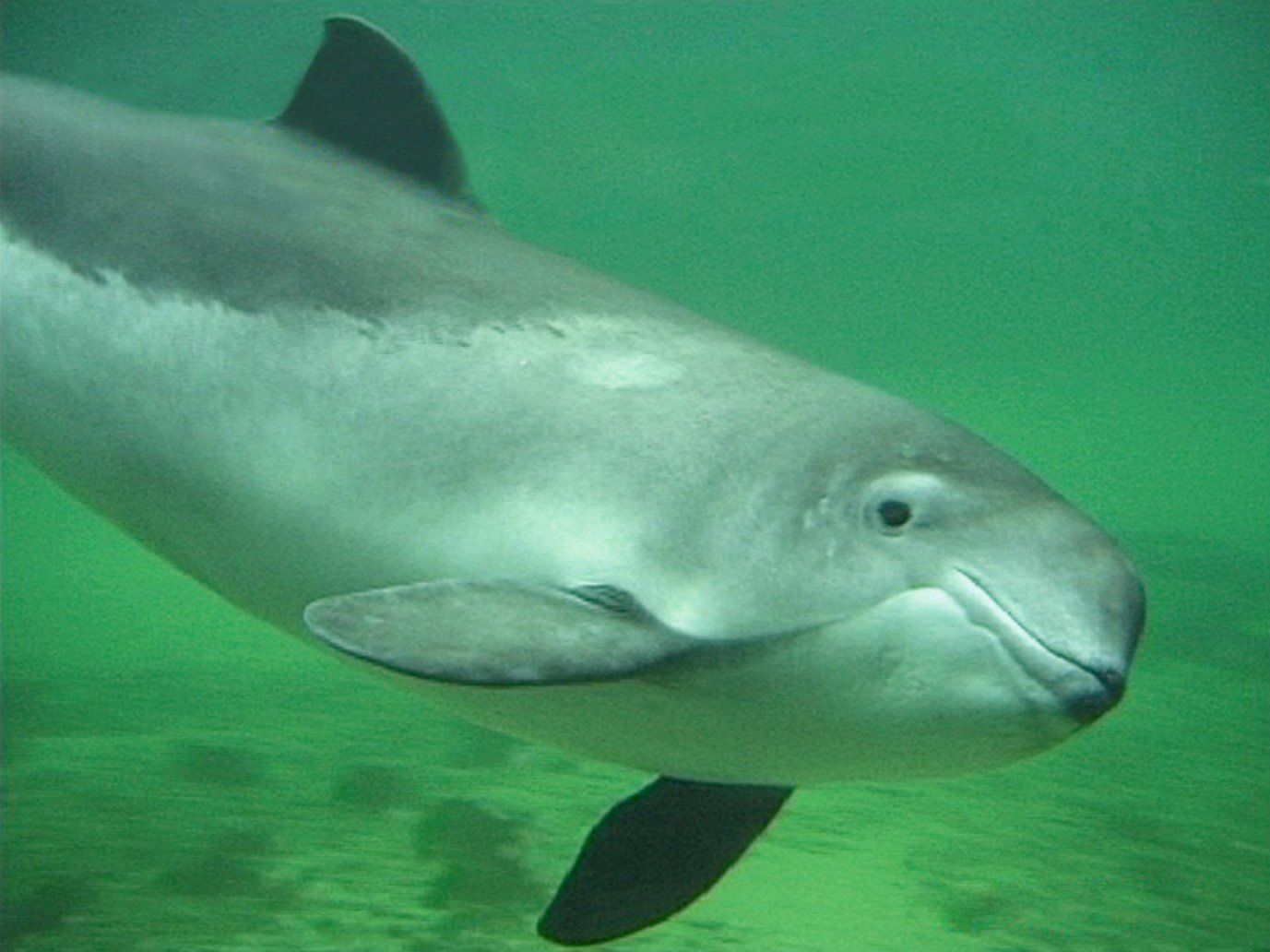

The Harbour porpoise ( Phocoena phocoena) is widely distributed throughout temperate and sub-polar shallow waters of the Northern hemisphere. High levels of this species have been taken as bycatch throughout the Northern hemisphere (Jefferson and Curry, 1994). The South-West of England is an important habitat for the Harbour Porpoise; however, it is also a place with high levels of gillnet fishing. In 2018, a study showed that over a third of harbour porpoises were stranded as result of entanglement and being caught as bycatch (Clear et al., 2018). Such incidents have led to a need for effective solutions to reduce porpoise mortality at the hands of gillnet fisheries.

Whilst numerous strategies, such as fishing gear modifications and deterrents, already exist to try to minimise these incidents from occurring, pingers remain the most effective option.

What are pingers? Pingers are acoustic alarms that are deployed with fishing nets to deter marine mammals that may happen to be nearby. They could understandably be mistaken as a banana; they are bright yellow and, well, shaped like a banana. They are attached at several locations across the net and emit intermittent sounds ranging between 10 and 140 kHz in frequency. These sound frequencies repel the marine mammals, whilst at the same time attracting fish to the fishing nets (Omeyer et al., 2020).

Now that we know what pingers are, what makes them so effective? Firstly, pingers are low in cost and require little change in fishing gear or practices. This makes them an attractive prospect for fishermen as they have relatively little effect on their traditional fishing practices. In addition, pingers are localised, short-lived and have no long-term effects on cetacean behaviour.

It is evident that pingers are responsible for a huge reduction in cetacean bycatch. One study showed that cetacean incidental catch was up to 50% lower in nets with pingers than those without. In addition, there was a reduced detection of harbour porpoises near fisheries where pingers were deployed (Omeyer, 2020). A reduced occurrence of porpoises is fundamental for limiting negative interactions between fisheries and porpoises.

Although there has been concern that pingers may cause habituation or habitat displacement in some populations of marine mammals, a recent study on harbour porpoises showed no evidence of this (Omeyer et al., 2020). Porpoises have been shown to return to their habitat relatively soon after the fisheries have left. In fact, adverse effects of pingers on marine mammals are predominantly as a result of misuse of equipment or poor compliance. A startling statistic showed that up to 64% of pingers were inactive due to nets not containing the correct number, which is about as useful as having none at all (Omeyer et al., 2020). It is, therefore, the responsibility of fisheries to ensure that pingers are used and maintained correctly.

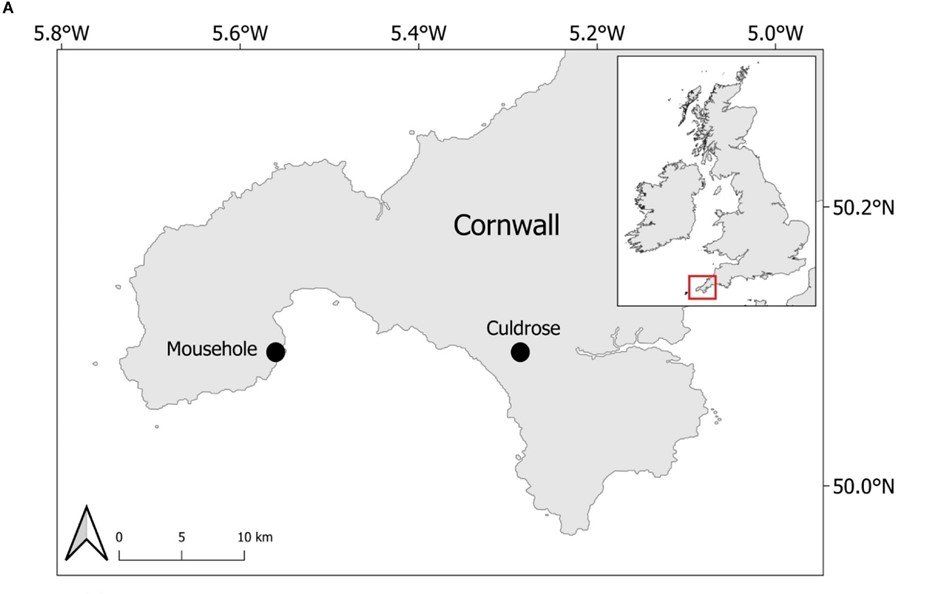

Let us end with a happy story about how pingers have resulted in a major reduction in the capture of harbour porpoise off the coast of Cornwall, United Kingdom. Before pingers were implemented, between 1000-2000 harbour porpoises were killed every winter and between 24 to 36 porpoises per week by just one fishing fleet. Two years ago, pingers were introduced to the fleet after major concern for the status of harbour porpoises. Astonishingly, there has since been no recorded captures of porpoises or dolphins in the area (Omeyer et al., 2020). This story shows how once used correctly, devices such as pingers can play a tremendous role in cetacean conservation.

References:

Clear, N., Hawtrey-Collier, A., and Williams, R. (2018 ). Marine Strandings in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly Annual Report. 1–22.

Das, K., Drouguet, O., Fontaine, M. C., Joiris, C. (2007). Viability of the Northeast Atlantic Harbour Porpoise and Seal Population (Genetic and Ecological Study). Université de Liège: Belgian Science Policy.

Davies, R. W. D., Cripps, S. J., Nickson, A., and Porter, G. (2009). Defining and estimating global marine fisheries bycatch. Marine Policy, 33, 661–672.

Jefferson, T. A., & Curry, B. E. (1994). A global review of porpoise (Cetacea: Phocoenidae) mortality in gillnets. Biological Conservation , 67(2), 167–183.

Omeyer, L., Doherty, P., Dolman, S., Enever, R., Reese, A., Tregenza, N., Williams, R. and Godley, B. (2020). Assessing the Effects of Banana Pingers as a Bycatch Mitigation Device for Harbour Porpoises (Phocoena phocoena). Frontiers in Marine Science , 285(7), 1-10.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE