The Implications of Climate Change for Manta Rays in The Maldives

Reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) are large zooplanktivorous elasmobranchs that are found throughout the tropical waters of the Indo-West Pacific Ocean. These warm waters are largely oligotrophic (devoid of nutrients) and so reef manta rays rely on hot-spots, where upwellings bring nutrient rich water to the surface and productivity is enhanced.

The largest sub-population of reef manta rays is found in the Maldives, with over 4,000 individuals identified through their unique ventral spot pattern. The Maldives is made up of 26 coral atolls and contains 67 cleaning stations and 104 feeding areas used by manta rays. Hanifaru Bay is known worldwide for the largest aggregation of manta rays on the planet, with hundreds of manta rays seen in the bay at a time.

Unfortunately, reef manta rays are listed as Vulnerable to Extinction on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and face many challenges. Targeted fisheries exist due to the demand of gill plates which are used in traditional Chinese medicine as a treatment for illnesses such as smallpox and chickenpox, despite no scientific evidence that they provide a cure. This is a very wasteful practise as few communities enjoy the taste of fresh manta meat. The rest of the animal is usually sold as low-quality fish meat or is ground up for animal feed. Thankfully, in the Maldives manta rays are protected from targeted fisheries. However they are still vulnerable to by-catch, habitat destruction and disruption from tourist activities. New evidence has also come to light that human induced climate change may be altering their environment.

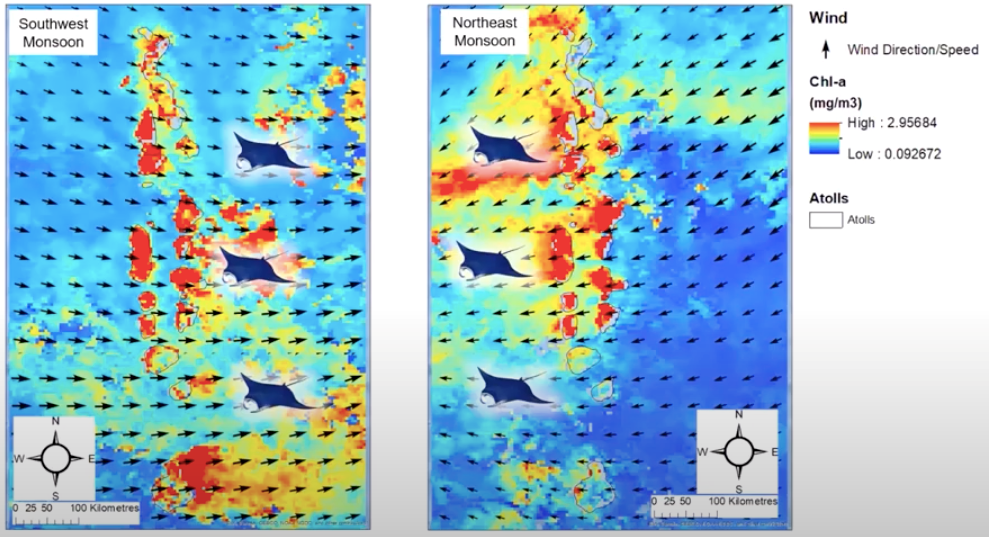

Manta rays migrate biannually within the Maldives and this migration is dependent on the South Asian Monsoon (SAM) which has 2 components: the southwest (SW) monsoon which occurs from May to October, and the northeast (NE) monsoon which occurs from December to March.

During the SW monsoon, wind drives ocean currents to the east, causing upwellings that bring zooplankton to the surface and consequently more sightings of manta rays on the east side of the coral atolls. This productivity is detected by satellite imagery which can detect levels of chlorophyll-a; the higher the level of Chl-a, the higher the productivity. During the NE monsoon the opposite occurs - wind drives currents to the west and there is greater productivity and more manta sightings on the west side of the atolls.

The SW monsoon is the dominant component. Its longer duration results in a longer period of enhanced productivity. There is also a greater food availability during the SW monsoon as an inflow of low salinity surface waters from the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal can suppress the productivity in the NE monsoon. The timing of the NE monsoon is determined by the onset and retreat of the SW monsoon.

Worryingly, there is increasing evidence that as global temperatures rise due to climate change, the monsoon seasons are being affected. This warming is thought to be shifting the timings of the onset and retreat of the SW monsoon, as well as weakening it. This weakening will cause intensified stratification, inhibiting zooplankton from reaching the surface waters and reducing the food supply for the manta rays. An increase in stratification over the last 60 years has caused a decrease in marine zooplankton by an estimated 20%. If this warming continues, the productivity of the ocean around the Maldives is likely to decline, further reducing the manta rays only food source which could have catastrophic effects for the population.

One way of protecting this species from human induced climate change is to expand and enforce marine protected areas (MPA’s) in the region. Although MPA’s cannot prevent changes in the SW monsoon dynamics, they can increase resilience to the impacts of climate change. Manta rays are able to adapt to these changes, but if they are simultaneously being threatened by another factor there can be a synergic effect. This is where the combined effect of both threats is greater than the sum of their separate effects. Therefore, by removing disturbance through MPA’s, the manta rays have a better chance of being able to adapt to the effects of climate change.

There are currently 42 small MPA’s throughout the Maldives, however they are fragmented and cover less than 1% of the total reef area. Additionally, only one of these MPA’s (Hanifaru Bay) has a management plan and active enforcement. The remaining 41 potentially existing as just “paper-parks” (MPA’s that exist on paper but in reality have no protection). Through the expansion of current MPA’s or the merging together of those that are close to each other, as well as proper enforcement, these protected areas can help to protect manta rays by increasing their resilience to climate change.

Reference:

Harris, J.L., McGregor, P.K., Oates, Y. and Stevens, G.M., 2020. Gone with the wind: Seasonal distribution and habitat use by the reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi) in the Maldives, implications for conservation. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE