THE FIN-TASTIC GALAPAGOS MARINE RESERVE.

Sophie A. Maycock | 15th of June 2020.

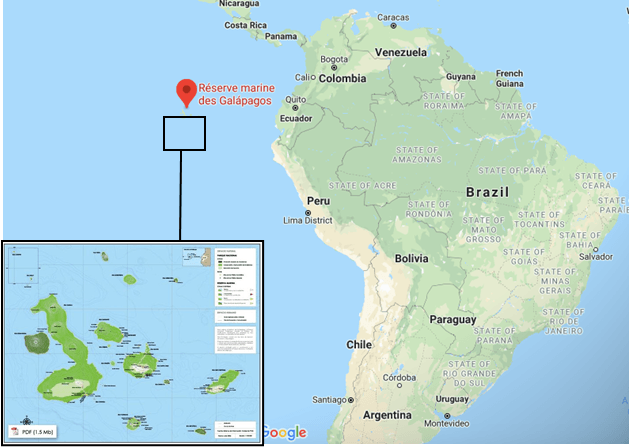

Imagine you are standing on a pristine beach…Glistening white sand slides into turquoise ocean, with gently lapping waves.Seal lions loll on the sand, marine iguanas bask on the rocks, and frigate birdsand boobies soar on thermals above. A UNESCO world-heritage site ofextraordinary natural beauty and remarkable biodiversity, protected as a marinereserve by the Organic Law of Special Regime for the Conservation andSustainable Development of the Galapagos (LOREG), 50,000 square miles ofpristine waters surround an archipelago of volcanic islands. You are in the Galápagos Marine Reserve, off the coast of Ecuador.

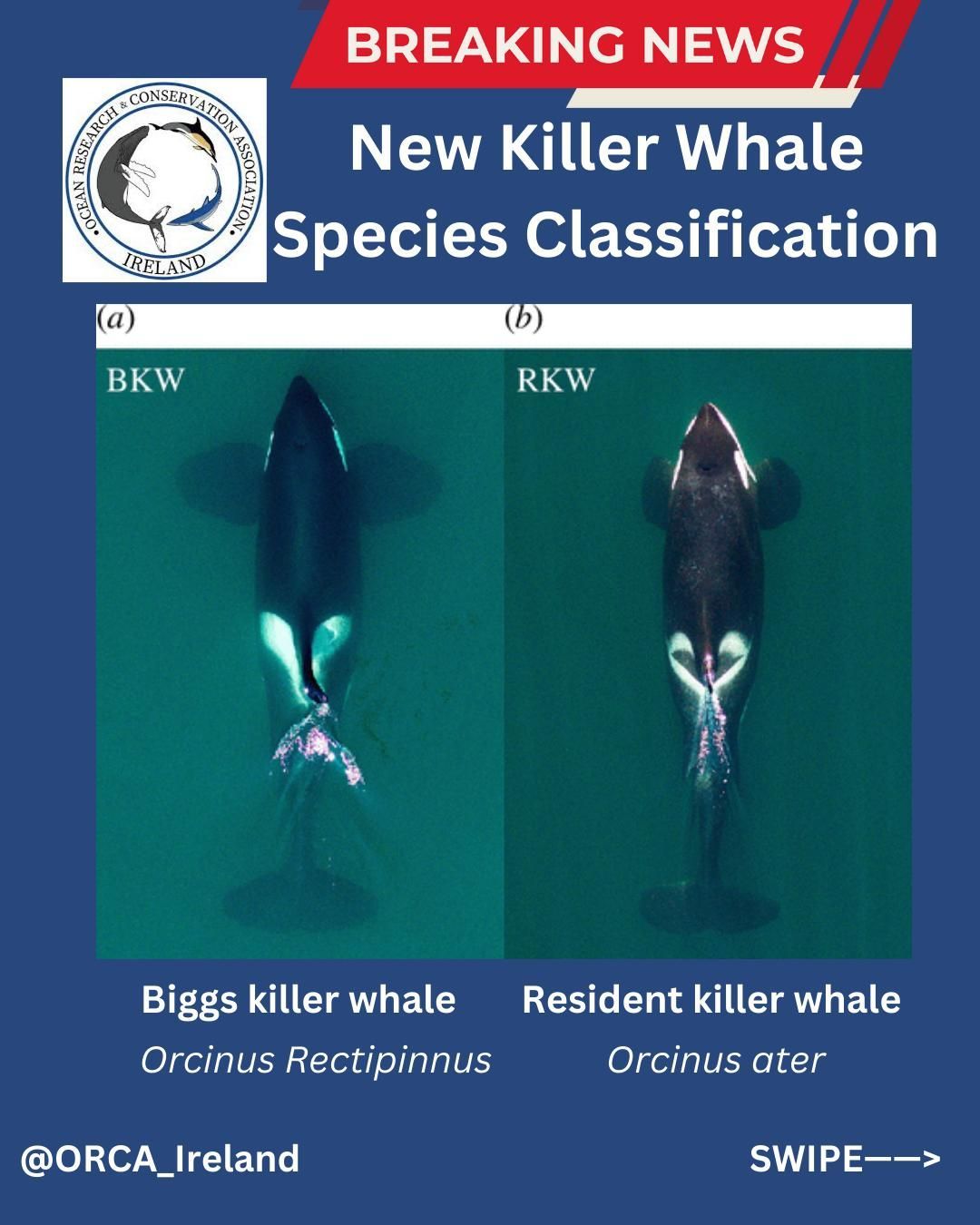

The Galápagos National Park has remarkable biodiversity, but it is particularly special to those of us who adore sharks.The region supports the highest concentration of sharks out of all the world’s oceans and is a critical habitat for several species of sharks which have conservation concerns. For the ‘critically endangered’ scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrnalewini ) the Galápagos is one of the last places where large schools can still be found. They use shallow waters in the reserve during their first few months of life to forage and grow, whilst being protected from predators (“

nursery habitats ”). The region is also an important habitat for ‘endangered’ whale sharks (Rhinocodon typus ) and ‘near-threatened’ black-tip reef sharks (Triaenodon obesus ), as it is thought they use the area to birth their pups (“

parturition habitats ”). The regional so supports ‘vulnerable’ silky sharks (

Carcharhinus falciformes ) (IUCN, 2020).

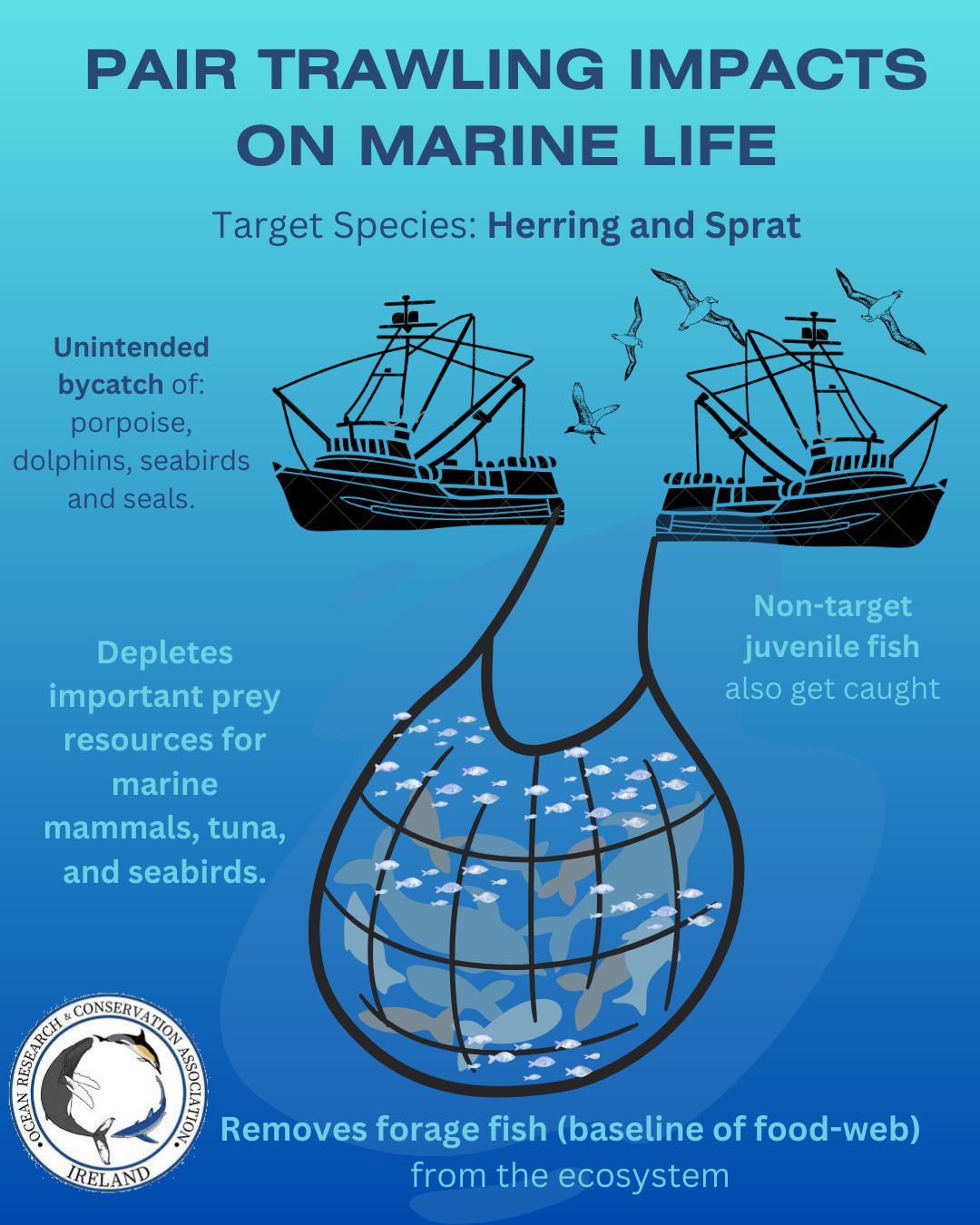

In order to keep this environment pristine, since 1998protection of the Galápagos has included blanket bans on industrial fishing. Only very small-scale artisanal fishing is allowed in certain areas and some areas are designated permanently as “

no-take zones ”,meaning any and all fishing (or “

extraction ”) is completely prohibited and punishable by law. No-take zones can be effective for conservation, as they can be placed to encompass critical habitats and provide refuges for threatened species.

However, the laws do not appear to stop some people…Sadly, there have been several incidents where fishing vessels have been seized within the boundaries of the marine reserve:

• In 2001 aCosta Rican fishing vessel was found with more than 1,000 shark fins onboard, which meant that at least 200 sharks had been fished from within the reserve.

• In 2011 anEcuadorian vessel was seized for fishing a total of 379 individuals from 7different species of sharks which were protected within the reserve.

• In 2017 300Chinese industrial vessels (some of which were long-line fishing vessels) were reported within the boundaries of the reserve.

• Later in 2017, the 300 strong Chinese fleet was once again detected in the vicinity of the protected area.

• Later in that same month, within the reserve, a Chinese vessel was seized with 300 tons of illegal catch of tuna (Thunnus spp.) and 6,000 finned IUCN- classified‘ threatened’ sharks (Alava, 2017).

If you are reading this and thinking, “But this is madness! How can they fish in a protected area!” or “They are breaking international laws, why do they do it!?”… then you and I are of one mind.However, it is important to understand that multiple factors come into play(political, social, cultural, economical, ethical, etc.) when trying to understand why people would choose not to respect the rules of a marine reserve. It is nuanced and complex. So why does it happen?

First, let’s consider the political aspect. Massive Chinese fleets can be found all over the world! Outside of Asia, they are also common in Africa, Central and South America, and they are responsible for depleting fish stocks in the waters of Senegal and several other African nations. This happens because China has depleted the fish stocks in their own oceans so severely, that the Chinese government expanded their fleet in order to increase fishing effort in distant-water fisheries. This is able to go on due to political corruption in regard to regulating fishing practices, which allows agreements between China and other nations to be granted (Alava, 2017).

Hand-in-hand with political effects come the economic impacts. China is responsible for approximately 60% of Ecuador’s government budget, which means Ecuador is often relatively indulgent in response toChinese rule-breaking, even in their own waters (Alava, 2017).

We must also consider the cultural pressures driving fishing within the Galápagos Marine Reserve. In several Asian countries, shark fin soup is considered a delicacy, which is often considered an impressive (and expensive) status symbol. The seizure of finned sharks in2017 represents at least 48,000 fins which can be sold on the Asian market.First grade fins (first dorsal fins, pectoral fins and lower caudal fins) are the most desirable, and therefore, the most pricey. The shark finning trade is driven by consumer desire for the product and the capitol that this generate scan sometimes overcome a person’s personal ethics and morality (Iloulian, 2017).

This all sounds quite overwhelming and hopeless, but that is NOT the case! Ecuador has made substantial efforts to limit illegal extraction within their waters, including deploying the coast guard and even the Navy; launching boats, and even helicopters, planes and submarines to track down law-breakers. If monitoring and surveillance efforts are continued and the area policed, it can be possible to protect this beautiful area for future generations.

If you would like to get involved or do your part to help, you can do so by:

• Choosing to eat only sustainably sourced fish. You can choose to only buy species of fish which are not threatened or choose to buy only from sustainable fisheries by looking for sustainability logos on packaging.

• Supporting ethical ecotourism companies when travelling in Ecuador, ensuring that the Galápagos Marine Reserve is valued for its live, rather than extracted wildlife resources.

• Choosing not to eat shark fin soup and to not buy dried shark fin products.

• Signing petitions towards banning shark finning globally, such as ORCA IRELAND'S "Stop Shark Finning" Petition

There are also many groups you can follow on social media in order to stay involved, such as our Shark Research Facebook Page and support our STOP SHARK FINNING Campaign.

• Donate to ORCA IRELAND working towards the protection of sharks in Ireland and around the globe!

Alava, J.J., Barragán-Paladines, M.J., , Denkinger, J., Muñoz-Abril, L., Jiménez, P.J., Paladines, F., Valle, C.A., Tirapé, A., Gaibor, N., Calle, M., Calle,

P., Reyes, H., Espinoza, E & Grove,

J.S. (2017). Massive Chinese feel jeopardizes threatened shark species around

the Galápagos marine reserve and waters of Ecuador: Implications for national

and international fisheries policy. I nternational Journal of Fisheries

Science and Research,

1

: 1001. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/55455441/Alava_et_al_2017-Massive_Chinese_Fleet_Jeopardizes_threatened_shark_species_in_the_GMR-Policy_Implications.pdf?1515180545=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DMassive_Chinese_Fleet_Jeopardizes_Threat.pdf&Expires=1591179635&Signature=b~7YDP803OwRb0rDO5RsE~7lakuaumXGu6gJnSnL38RlU3O715Wx~RnRQLyIgCR-zBCorTsnyHGG-EsVo548YN8xj~hn30vXy0zJ2XkbRlqvkv1SImdIg~lDRkrEb3QeAKbgg8Jr8MubCOXRvvRrPemMjQTURQEKJH1nW~~gMX~lzs7UR62BA5s2GlXjwvo9lwIVwI0F1bluX3RRG0UrRMIKRGjpuS2PvuCcLLBoOOFenUB2ADSceuEPUigvfLATEPMQIFPLePEFzn9Qy3BfGP-eqFT7-vL8N8qA8lDfPKtwrXlE5ziFh55cfnL8uiTqibiJ5cqmFe~dxtfbm5ZZqg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

Bland, L.M., Keith, D.A., Miller,

R.M., Murray, N.J., Rodríguez, J.P. (2017). Guidelines for the application

of IUCN Red List of Ecosystems categories and criteria.

IUCN Commission on

Ecosystem Management (CEM). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318849077_Guidelines_for_the_application_of_IUCN_Red_List_of_Ecosystems_Categories_and_Criteria_version_11

Iloulian

J. (2017). From shark finning to shark fishing: A strategy for the U.S. &

EU to combat shark finning in China & Hong Kong. Duke Environmental Law

and Policy Forum

27

: 345-364.

IUCN.

(2020) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-1. https://www.iucnredlist.org

. Accessed 3rd June 2020

13:50.