Solving the world's Plastic Pollution Problem!

In order to solve the world's plastic pollution crises we need to better understand the extent of the problem. Last year, many strides were taken to quantify the abundance and distribution of plastics in our oceans, but 2020 will be an important year that could see the tide turning on the petrochemical industry, if public pressure on governments overrides corporate influences. Read more about the current state of plastics in our oceans and take our "Plastic-Free-Pledge" for 2020.

For most of the world, 2019 was the year the petrochemical industry and mega food, drink and beauty companies locked the world even further into fossil fuels, creating mountains of plastic for communities and future generations to deal with and making it almost impossible to keep global temperatures in check.

Cheap shale gas from US fracking boom since 2010, has driven a surge of billion-dollar investments in new industrial plants for plastics production that separate ethane from gas to produce ethylene. Over the last decade, the petrochemical industry has invested $200 billion, and with $100 billion more planned to be invested to help plastic production is grow to 40% by 2030.

The link between plastic production and climate change and the implications it has on the natural environment are only now being understood. Twenty years ago, the effects of plastic on our climate were little known, now the production and disposal of plastic uses 14% of all the world's oil and gas. Plastic production is expected to continue to grow by 2050, by which time the plastic production industries emissions could rise to 2.75 billion tonnes a year, which plastic driving half of all oil demand growth.

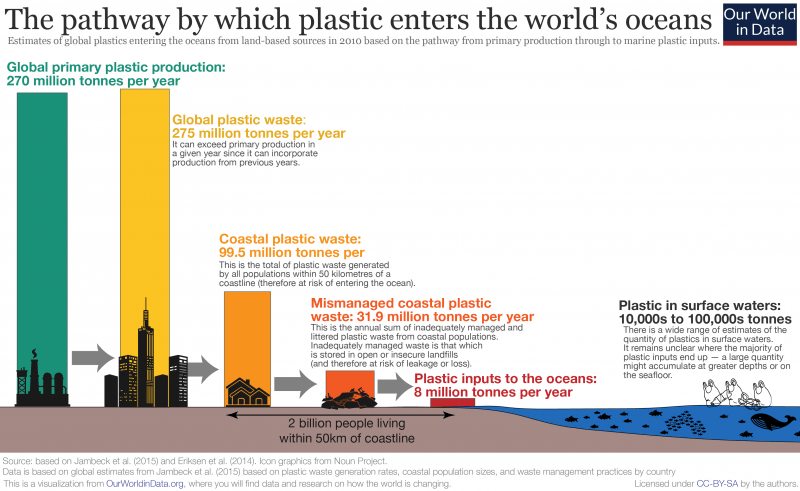

Despite attempts rom the United Nations to have corporations pledge to reduce plastic production, the demand for plastics grew a further 3.5% in 2019, and maybe as much as 16% in Asia. The latest statistics suggest 359 million tonnes of plastics were produced in 2018, with nearly one third going to single-use plastic packaging and less than 10% recycled. The remaining plastics ended up in landfills, were burned in incinerators (adding to emissions and air pollution), or was left uncollected, with approx. 8 million tonnes making its way to our oceans via rivers.

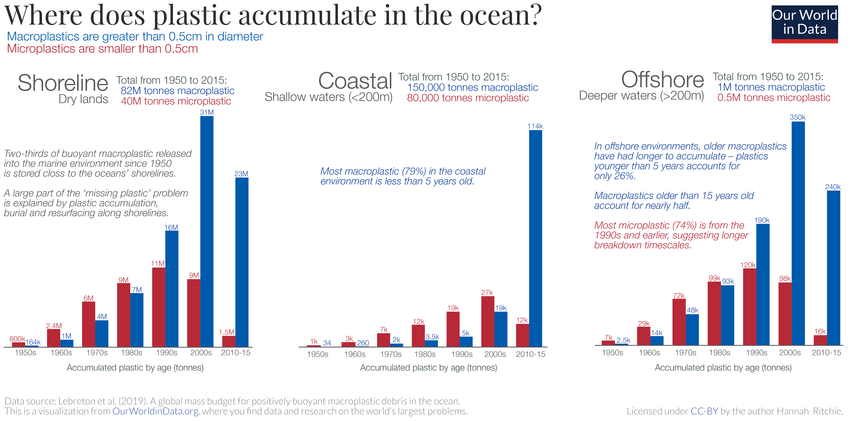

To gain a better understanding of what happens to plastic waste when it enters the ocean, Lebreton, Egger and Slat (2019) created a global model of ocean plastics from 1950 to 2015. This model uses data on global plastic production, emissions into the ocean by plastic type and age, and transport and degradation rates to map not only the amount of plastic in different environments in the ocean, but also its age.

The authors aimed to quantify where plastic accumulates in the ocean across three environments: the shoreline (defined as dry land bordering the ocean), coastal areas (defined as waters with a depth less than 200 meters) and offshore (waters with a depth greater than 200 meters). They wanted to understand where plastic accumulates, and how old it is: a few years old, ten years or decades?

Two categories of plastics are shown in the infographic above; blue are ‘macroplastics’ (larger plastic materials greater than 0.5 centimeters in diameter) and shown in red microplastics (smaller particles less than 0.5 centimeters broken down over time).

There are some key points we can take away from these graphs:

- The vast majority – 82 million tonnes of macro-plastics and 40 million tonnes of micro-plastics – is washed up, buried or resurfaced along the world’s shorelines.

- Much of the macro-plastics in our shorelines is from the past 15 years, but still a significant amount is older suggesting it can persist for several decades without breaking down.

- In coastal regions most macro-plastics (79%) are recent – less than 5 years old.

- In offshore environments, older microplastics have had longer to accumulate than in coastal regions. There macroplastics from several decades ago – even as far back as the 1950s and 1960s – persist.

- Most micro-plastics (three-quarters) in offshore environments are from the 1990s and earlier, suggesting it can take several decades for plastics to break down.

Whilst we try to tally ocean inputs with the amount floating in gyres at the centre of our oceans, most plastics may be accumulating around the edges of the oceans. This would explain why we find much less in surface waters than we’d expect.

Accumulated plastics are much older than previously thought; macro-plastics appear to persist in the surface of the ocean for decades before breaking down. Offshore we find large plastic objects dating as far back as the 1950s and 1960s. This goes against previous hypotheses of the ‘missing plastic’ problem which suggested that UV light and wave action degrade and remove them from the surface in only a few years.

2019, was also the year the world revolted against climate change and plastic production, when going "plastic-free" became trendy in Europe, when governments introduced new laws regarding plastics, and hundreds of potential solutions were initiated.

Public beach cleans were at an all time high last year across Britain and Ireland, but the extent of the problem was highlighted in November 2019 when a sperm whale washed up with 100 kg of plastics in its stomach. Read more here.

Such stranding were frequent in 2019, with plastic-filled cetaceans beaching themselves in Wales, the Philippines, Indonesia, Italy and the U.S.

These events helped to create positive steps towards the global commitment on plastic, introduced in late 2018, which managed to get 400 of the world's biggest corporations to pledge to use less and recycle more. Combined these companies contributed to more than 20% of all plastic packaging produced. Companies such as, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Morrisons and Waitrose raced to ditch hard-to-recycle “black” plastic from their ranges and to accelerate the amount of recycled material they use.

Novel ways to collect plastic from rivers and oceans were introduced. The Ocean Cleanup project, for example, launched the Interceptor, a barge-like vessel theoretically able to remove 100,000 kg of plastic waste per day from heavily polluted rivers. In Amsterdam, Waternet, which manages the city canals introduced a "bubble barrier" to catch floating debris.

By the end of 2019, the war between the petrochemical companies and those who would turn their back on plastic was fully engaged, but was still being largely won by the petrochemical industry.

2020 is a critically important year. In June 2020, the UN will host an oceans conference in Portugal at which worldwide progress on plastic pollution will be assessed, and countries will pledge to prevent more plastic pollution. Many proposed government bans should also come into force and hundreds of smaller initiatives to recycle more and reduce pollution should start to grow and make a difference.

What is certain is that calls for a reduction in plastic use will grow louder and the industry will resist. But unless ways are found to use less, most of the efforts to stop the flood of plastic entering the environment are likely to prove temporary and insufficient.

We need your help this year, every individual in the world can consciously decide to not use plastic or at least reduce your use of plastic. Instead look for alternatives and sign up to our "Plastic-Free-Pledge" for 2020, especially if you run your own business - "Go Blue" this year and help solve the worlds plastic pollution problem.

Click here to TAKE THE PLEDGE!

SHARE THIS ARTICLE