Skates and Rays of Ireland.

Our oceans are teeming with life and holds about 95.5% of the world's’ water. In Ireland we are never too far from the coast however, we do not know how diverse our oceans are. We are incredibly lucky with our unique position along the gulf stream on the West of Ireland but more importantly we are fortunate to have waters rich in biodiversity.

Rays and skates have been on this plant for more than 400 hundred million years and were present 1 million years before the dinosaurs ever existed! Sharks, Rays and Chimeras are in the group known as Chondrichthyes . There is an estimated 500 skate and ray species in the world, with a whopping 28 of these species found in Ireland. They are found in almost every ocean and even at depths of 2000 meters. Irish waters are vital for many of these species with regards to food and nurseries.

So, what is the difference between a ray and a skate and what do they look like?

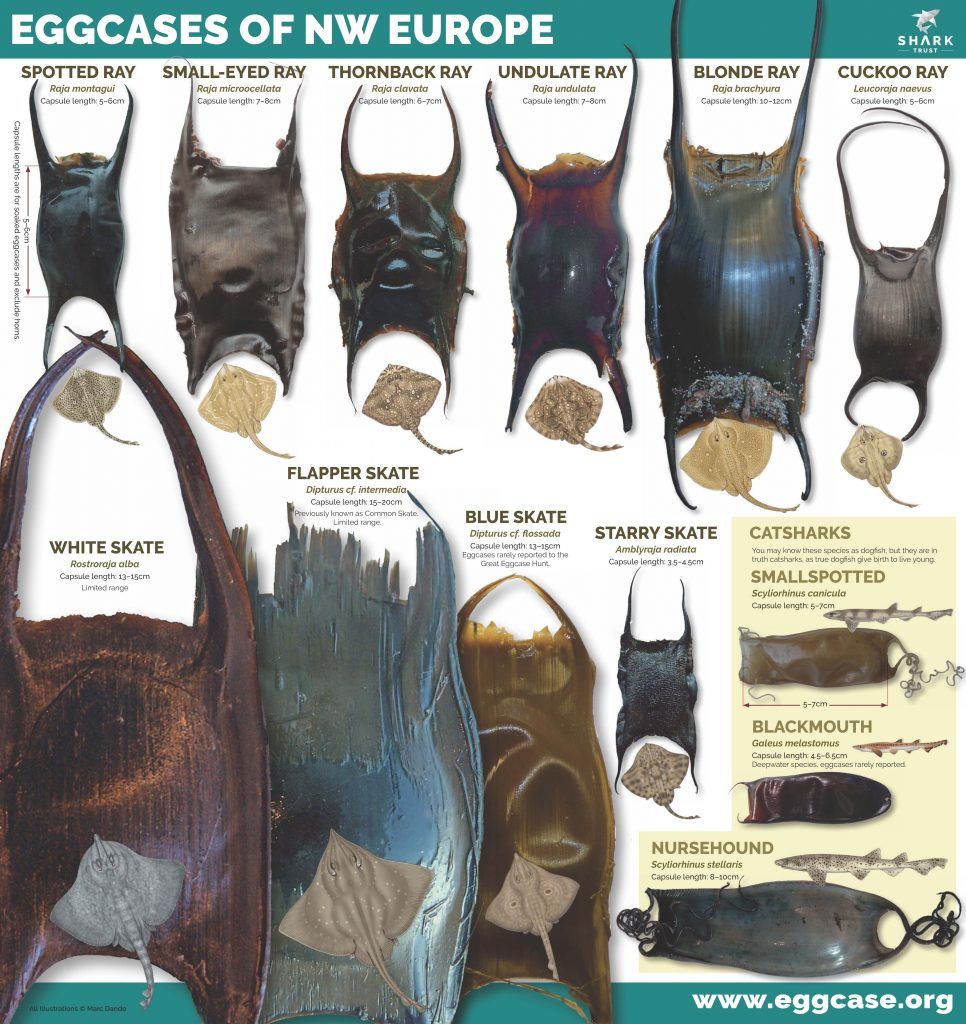

‘Rays’ is an overall term used when speaking of true rays and their closely related cousins’ skates. Rays and skates are a species of fish, closely related to sharks and are dorso-ventrally flattened. This gives them an added advantage to be able to glide along the sea-floor. Rays and skates are very similar in appearance however, there are differences. Rays give birth to live pups whilst skates produce egg cases (oviparous) that are distinctive to the species. The Shark Trust have excellent egg-case identification guides. Skates have a tail that is stockier and does not have a stinging spine. Rays have a thinner tail and sometimes have a stinging spine(SharkTrust, 2019). Skates and Rays bury themselves under sand on the sea-floor to protect themselves from predators. There are two breathing holes called spiracles located near their eyes which allow them to breath when covered in sand. The presence of these spiracles means that rays have the ability to rest on the sea-floor whereas most other sharks must keep swimming to keep water moving across their gills or else they will not be able to breath. Their mouth is on the underside of their body which enables them to feed on benthic animals.

What species of rays and skates are in Ireland?

The following is a description of some of the species of skates found in Ireland. You might have encountered the egg-cases of some of these animals.

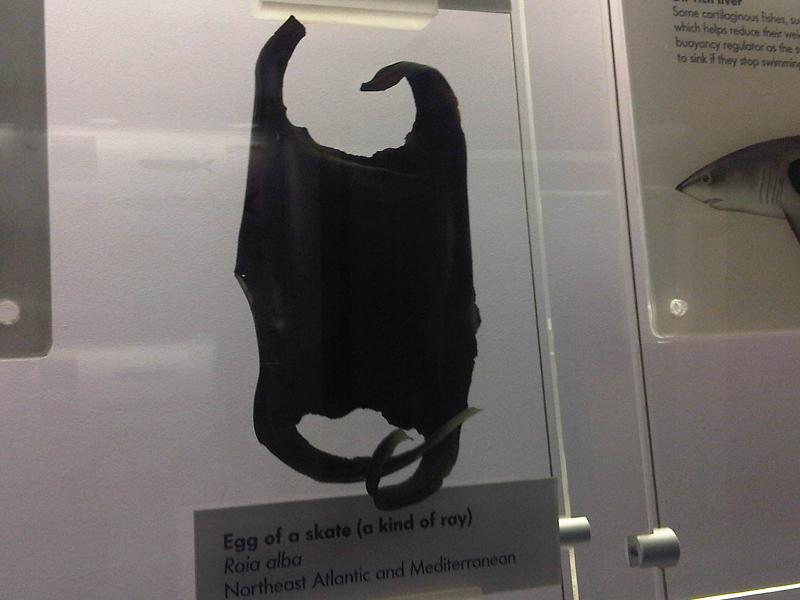

White Skate (Rostroraja alba)

This species of skate is classified as endangered globally (A2cd+4cd) according to the IUCN Red List with a decrease in population trend. In Ireland, the species is much more vulnerable with a status of critically endangered (A2bd)(Clarke, et al., 2016). It is a large species of skate that produces the largest egg case found in Ireland. It has a narrow snout and is typically a grey colour on top. The underside of the white skate is white with a black border sometimes fading to a grey border in adults(CentralFisheriesBoardIreland, 2003). People are prohibited from fishing this species of skate.

Flapper Skate/Common Skate (Dipturus batis)

Listed as critically endangered worldwide, the flapper or common skate was once common as its name suggests. However, overfishing has had a huge impact on the population as the number of catches in the 20th century dramatically declined. It was once targeted by fisheries but now is more commonly caught as by-catch(Clarke, et al., 2016). It is the largest living skate measuring to a length of 250cm (Dulvy, et al., 2006). The egg-case is large and resembles a piece of wood washed ashore.

Undulate Ray (Raja undulata)

The undulate Ray is a magnificent species of skate with its very distinctive markings and patterns on a(Clarke, et al., 2016) light tan coloured background. It grows to 3.5 feet and is most commonly found in Tralee Bay, Co. Kerry (CentralFisheriesBoardIreland, 2003). The egg-case does not have keels and is very similar to the spotted ray egg-case however, it is generally larger in size. It is a medium sized skate typically found inshore or in shallow waters. Data from catches in Tralee Bay show that the catches have decreased by 60-80% since the years 1981 (Coelho, et al., 2009). Tralee Bay is closed off from commercial fishing to protect species such as the Undulate Ray amongst others (ICES 2007) however, recreational fishing is still permitted.

Blonde Ray (Raja brachyura)

This is a beige to light brown coloured ray on its upper-side with many darker spots. It is white underneath. Its body is almost a diamond shape with a small snout. It can be found inshore and on coastal shelf waters. It is typically found on sandy shores(InlandFisheriesIreland, 2014)and feeds on benthic animals. The status for this species of skate in Ireland and Worldwide is near threatened (Ellis, et al., 2009). This is mainly due to the over exploitation by commercial fisheries. The female lays about 30 eggs between February and August after a gestation period of seven months(Stehmann & Bürkel, 1984). This species of skate is most commonly found in the South and South-West of Ireland however, it can be seen or caught anywhere along the entire coastline of Ireland.

Cuckoo Ray (Leucoraja naevus)

This ray produces one of the smallest egg-cases with long horns. The body is a tan colour with two distinctive black spots overlaid with yellow or white spots on both wings.(CentralFisheriesBoardIreland, 2003). It has a short tail and small snout. It is listed as vulnerable in Ireland though the global population status is of least concern. The cuckoo ray can be found offshore over gravel or sand substrate in the Irish sea(Clarke, et al., 2016).

Spotted Ray (Raja montagui)

This skate is considered of least concern globally according to the IUCN Red List which was last assessed in 2007. It is typically found in sandy coastal areas. The spotted ray egg-case is similar in appearance to the undulate ray. It has no keels but is typically smaller than the undulate ray egg-case. It is a small bodied skate, much smaller than other skate species which may make it less vulnerable to impacts of fishing(Clarke, et al., 2016). The upper-side of the body is covered in many darker spots that do not extend to the wing edge as in the blonde ray. It also has a pale spot surrounded by darker spots on each wing. They are known as eye spots(InlandFisheriesIreland, 2014).

Thornback Ray (Raja clavate)

The thornback ray is a medium sized skate with a long tail. It is distinctive from other skates due to the presence of spines along its dorsal surface and tail. Its dorsal surface is a dark brown or grey with varying patterns while the underside is a white colour with darker edges(SharkTrust, 2019). It is a nocturnal animal and can be found in a variety of habitats such as mud, sand and rocky areas to a depth of 300 meters (Wheeler 1969, Stehmann and Buerkel 1984 &(Wheeler, 1969). The egg-case of the thornback ray is very distinctive. There are keels along the edge of the egg-case. It is roughly 50-09 mm in length and can be confused with the blonde ray egg-case however, the thornback egg-case is smaller. The status for this species in Ireland is good and is listed as least concern whereas globally, the thornback is listed as near threatened (Ellis, 2016)

Painted/ Small-eyed Ray (Raja microocellata)

It's body is a diamond shape with a short nose and tail. On the upper-side it is a sandy colour with white markings. It has a white underside. It can be found in the south to south-west of Ireland such as Cork and Kerry. It is listed on the IUCN Red list as near threatened globally. It lays between 50 and 60 eggs each year from June to September(Ryland & Ajayi, 1984). Geographically this species is rare nevertheless, it can be abundant in some local areas such as the Bristol Channel. The egg-case capsule has keels and long filamentous horns.

Common Stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca)

This ray is considered endangered in Ireland with little information to assess the status of this species globally. Its distribution is patchy though there is an isolated population that occurs seasonally in Tralee Bay, Co. Kerry. Anglers catch this species however, they do release them after. There are no measure in place currently to protect the common stingray(Clarke, et al., 2016). It has a short snout and a long thin tail. There is a spine at the end of the tail and can measure up to 12 meters in length. The dorsal or upper surface of the stingray is a brown to olive in colour whilst the ventral surface is white but darker around the edges(SharkTrust, 2019).

Threats to skates and rays in Ireland

There is a major concern in relation to the stock of some chondrichthyans, rays included, that are being impacted by fishing(Stevens, et al., 2000). Many of our rays are caught as bycatch or become entangled in netting. There has notably been a drastic decline in the populations of rays such as the Common Skate which was at the “brink of extinction” by fishing activities for example, trawling in the Irish Sea (Brander, 1981; and Stevens, et al., 2000). Overfishing of prey species is another impact affecting our already vulnerable skates.

Demersal fishing or benthic fishing is one type of fishing carried out in Irish waters. It is the use of trawled gear on species such as monkfish, plaice, hake and gadoids. Ireland, the UK and France are some of the countries that carry out this type of fishing in Irish waters. Some ray species are caught(Clarke, et al., 2016)as by-catch.

The predecessors of the Inland Fisheries Ireland started a research programme in 1970 called ‘Tag-A-Ray’. Today this research still continues (Fitzmaurice et al. 2003a-f). It is essential for assimilating data of some of the rarer skates. The data helps to build a picture and highlights declines in skate populations when compared to catches from previous years. The Tag-A-Ray programme does not allow participants to harm any of the elasmobranch species caught. Some of skate species such as the white skate, flapper skate and blue skate “receive a high level of protection under the EU Common Fisheries Policy, though this is not an effective measure in every case”. These fish must not be fished or transhipped as they are on the prohibited species list. The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is the main body associated with management and conservation for cartilaginous fish in Ireland(Clarke, et al., 2016).

Factors such as long species, late maturation and the fact that the females may not breed every year means that it is very hard for populations to recover from destructive human activities. As said before, these species have been here longer than the dinosaurs and we as humans must start protecting our oceans. We can help by spreading awareness and by reducing our impacts on the ocean.

References

Brander, K., 1981. Disappearance of common skate Raia batis from Irish Sea. Nature, Volume 290, pp. 48-49.

CentralFisheriesBoardIreland, 2003. Irish Sport Fishes: A Guide to their Identification, Ireland: Central Fisheries Board.

Clarke, M. et al., 2016. Ireland Red List No. 11 : Cartilaginous fish (Sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras), Dublin, Ireland: National Parks and Wildlife Service & Department of Art, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht affairs..

Clarke, M. et al., 2016. Ireland Red List No. 11; Cartilaginous fish [Sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras], Dublin, Ireland: National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs..

InlandFisheriesIreland, 2014. Blonde Ray.

[Online]

Available at: https://www.fisheriesireland.ie/Tagging/blonde-ray.html

[Accessed 23 02 2019].

InlandFisheriesIreland, 2014. Spotted Ray.

[Online]

Available at: https://www.fisheriesireland.ie/Tagging/spotted-ray.html

[Accessed 01 03 2019].

Ryland, J. S. & Ajayi, T. O., 1984. Growth and population dynamics of three Raja species in Carmarthen Bay, British Isles.. Journal de Conseil Internationale de Exploration de la Mer, Volume 41, pp. 111-120.

SharkTrust, 2019. Skates and Rays.

[Online]

Available at: https://www.sharktrust.org/en/skates_and_rays

[Accessed 16 02 2019].

SharkTrust, 2019. Thornback ray distribution.

[Online]

Available at: https://www.sharktrust.org/en/thornback_ray_results

[Accessed 25 02 2019].

Stehmann, M. & Bürkel, D. L., 1984. Rajidae. In: Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean.. Volume 1.

Stevens, J. D., Bonfil, R., Dulvy, N. K. & Walker, P. A., 2000. The effects of fishing on Sharks, Rays and chimaeras (chondrichthyans) and the implications for marine ecosystems.. ICES Journal Of Marine Science, Volume 57, pp. 476-494.

Wheeler, A., 1969. The Fishes of the British Isles and North-West Europe.. Macmillan, London,UK.: s.n.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE