Shark Nets Causing More Harm than Good.

Shark nets are strung across the east coast of Australia to protect those swimming at popular beaches from sharks, but what about the other marine animals getting tangled in the gillnets? New research identifies which animals are being compromised and the mortality rates of animals caught in these nets.

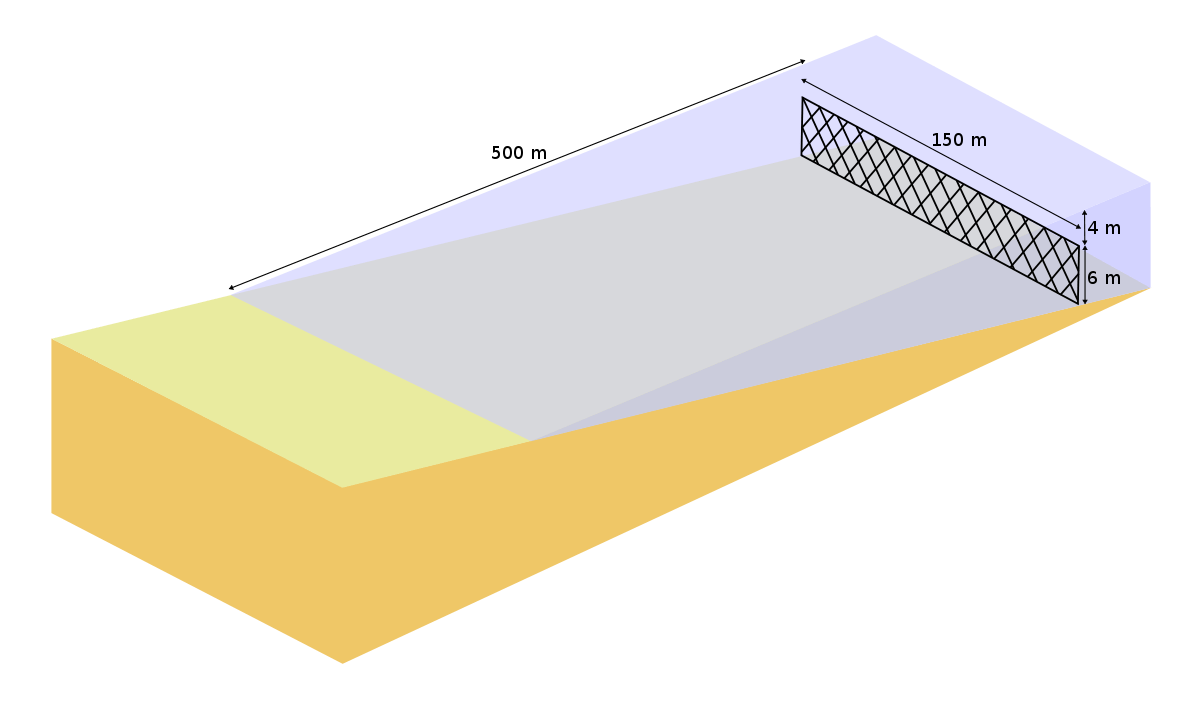

Many beaches around Australia and South Africa have implemented shark nets as a response to high cases shark attacks or sightings. They are heavily predominant in Australia with 136 nets strung along the east coast. By having these nets at popular beaches, local governments aim to protect beach goers from seemingly aggressive shark species in the area. Most Australian shark nets comprise of gillnets that range from 150 to 200 meters long and tend to be 6 meters deep. Gillnets are effective in catching animals as they are designed to restrict the head and consequently suffocate most animals.

These gillnets tend to have excessive bycatch of non-targeted species which is particularly worrisome to a number of threatened marine megafauna species that reside in Australia. This has become quite a conservation concern as of the thousand species of sharks and rays globally, at least a quarter are thought to be at risk of extinction by the IUCN red list. Overexploitation of fisheries is the key anthropogenic threat to these animals. It is notoriously difficult to quantify the mortality of sharks and rays. However, the most recent studies in 2013 estimated a global annual shark harvest of roughly 500 000 tonne with an additional 940 000 tonne discarded dead as either bycatch or a result of being finned. This equates to a total mortality of roughly 100 million individuals. However, gaps in research mean that this number is probably much higher. Sharks and rays are targeted by various active and passive fishing gears, much of which includes longlines and gillnets, like that used for shark nets.

Gillnets are favoured in many coastal areas due to their low operational costs and ability to be used for a wide variety of species. Despite the increasing conservation concerns in regards to many shark species, gillnets have been deployed off swimming beaches across both Queensland and New South Wales to catch large, potentially dangerous sharks. Historically the target species have been white sharks and most sharks greater than 2meters in size. The nature of these nets means they are likely to catch non target species as well, including small sharks and rays as well as charismatic megafauna like turtles, whales, and dolphins. Many of the species threatened by bycatch are listed as ‘Near Threatened’ or an even higher category of concern by the IUCN. However, it is important to note that the fate of the animals caught in these nets is heavily influenced by biological, environmental, and technical factors.

A study by Broadhurst and Cullis was conducted involving the catches from shark nets deployed off five beaches in northern New South Wales across two six month periods during Australia’s summer. All gillnets were 150 meters wide and 6 meters tall, they were deployed at depths between 0.5 and 2 meters from the surface. These nets were all equipped with acoustic deterrents that aim to minimise the number of dolphins and whales caught. In addition to assessing whether the animals caught were dead or alive, the data collected from this study analysed how severely they were entangled.

The results from this study showed that 420 individuals across 22 different species were caught, most of which were mildly or moderately entangled. The greatest mortalities were recorded for common blacktip sharks and great hammerheads. The total mortality rate of the animals caught in the shark net were 49%. More specifically, the mortality rates for specific groups of animals are as follows, 86% for sharks, 36% for rays, 100% for fish, 45% for turtles and 100% for dolphins. This is of particular interest as all eight dolphins were caught on nets that were rigged with the types of acoustic deterrents that are meant to stop that exact situation from happening. The total of immediate mortality observed in this study is comparable to the estimated global average which sits at 40% for gillnets. If this research continues, this data can be utilised to guide recommendations for future gillnet deployments. In order to protect threatened species, further research should be conducted to mitigate non target species being caught by shark nets.

Reference:

Broadhurst MCullis B (2020) Mitigating the Discard Mortality Of Non-Target, Threatened Elasmobranchs In Bather-Protection Gillnets. Fisheries Research 222:105435.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE