Saving whales to save ourselves; natures remedy to the climate crisis!

Protective measures for whales can help limit greenhouse gas emissions and fight global warming. One whale may be worth 1000 trees when it comes to saving our planet.

Earth is in a climate crises with biodiversity and our very own species at risk of extinction, but efforts to mitigate against climate change face a number of significant challenges.

The first challenge is to find ways to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and lower its impact on global temperatures. The second challenge is to finance the technologies needed to put preaching into practice. To date, proposed solutions to the global climate crises, such as capturing carbon directly from the air and burying it deep within the ground are complicated, not validated and costly. However, there is a "low-tech" model already available that could be effective and economical.

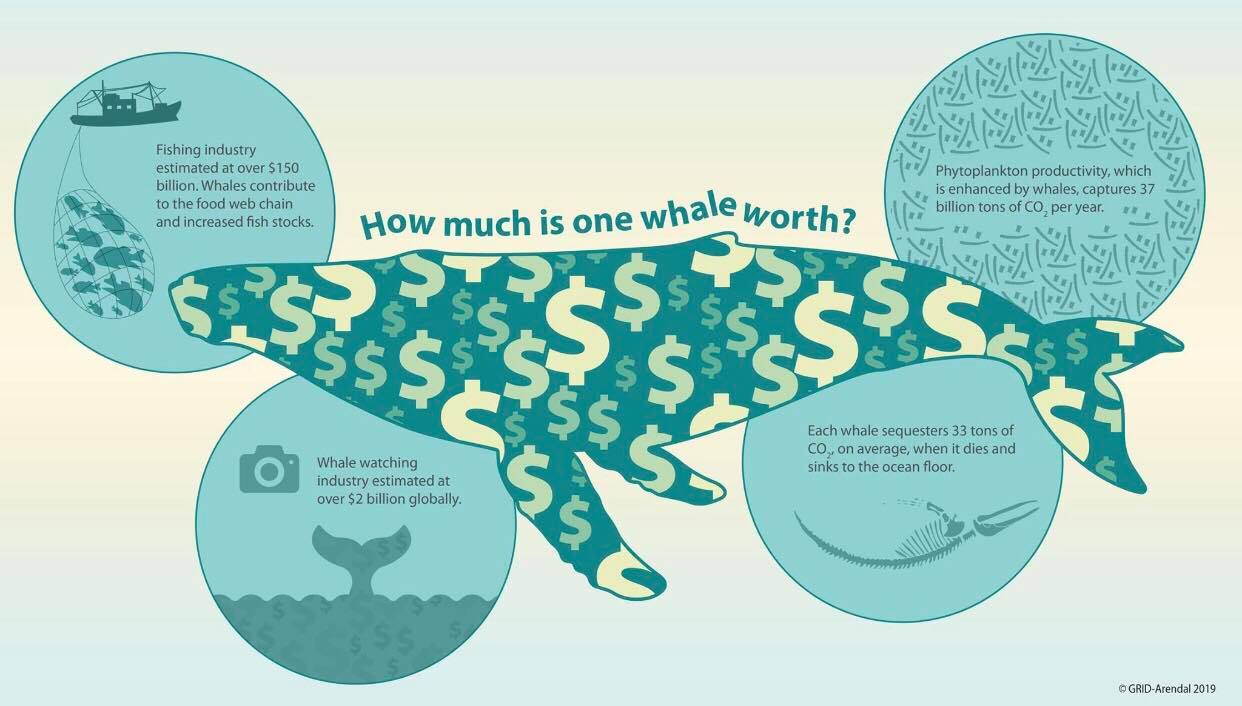

Such an opportunity presents itself in the protection of large whale species such as the blue, the fin and the humpback whale to capture more carbon from the atmosphere by increasing global whale populations! Recent studies have shown that the great whales or rorquals are particularly good at capturing carbon from the atmosphere (Ronan, 2014). Whales accumulate CO2 in their bodies during their long lives and when they die, their carcass falls to the oceans depths, sequestering 33 tons of C02 on average, removing this carbon from the atmosphere for centuries. A tree in comparison, only aborsbs 48 pounds of carbon/year.

As current population numbers of great whales are only a fraction of what they once were pre commercial whaling, (for example blue whales are reduced to only 3% of their previous abundance), protecting whales could provide significant carbon capture. Therefore, the benefits from the ecosystem services whales provide to us and our survival today is limited by their reduced population numbers.

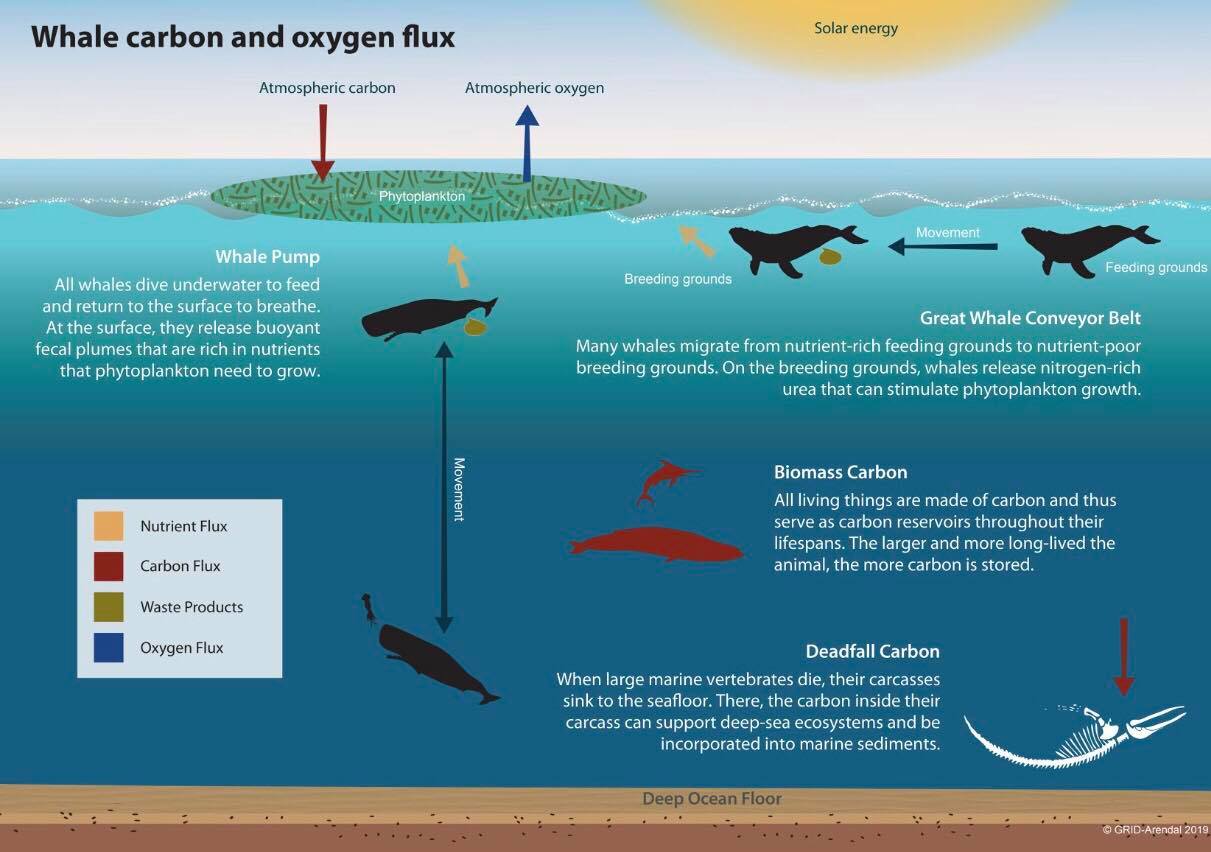

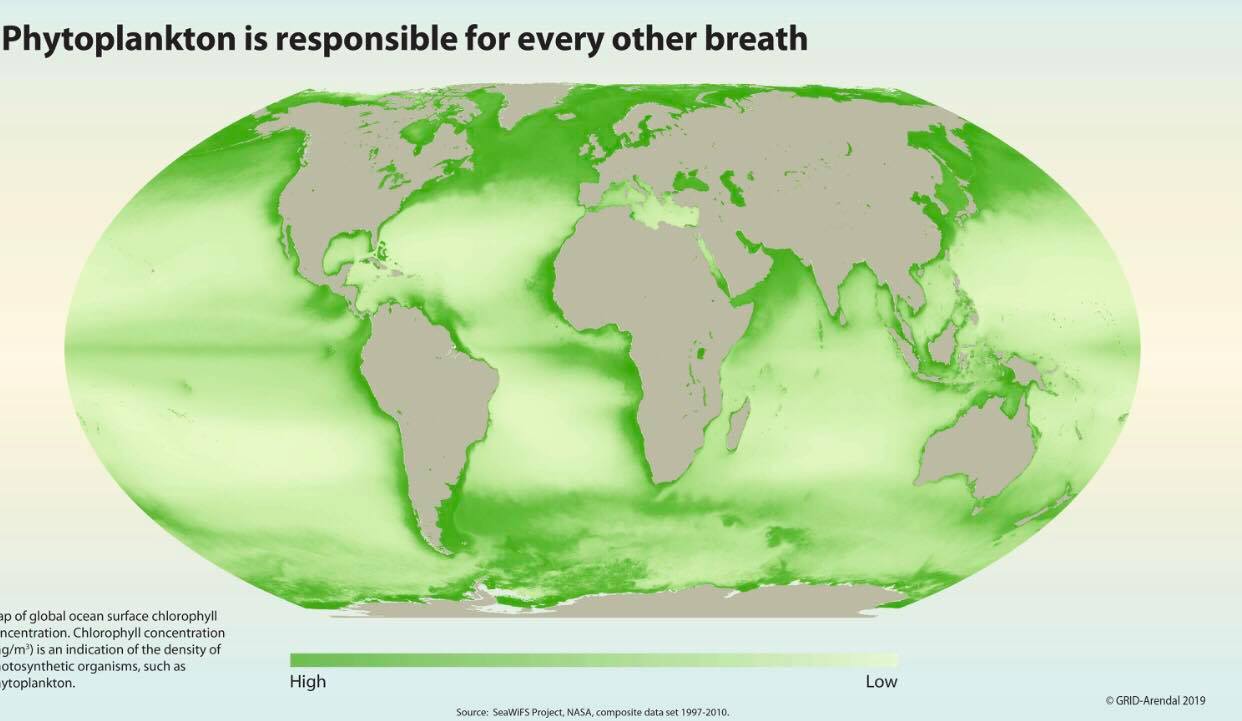

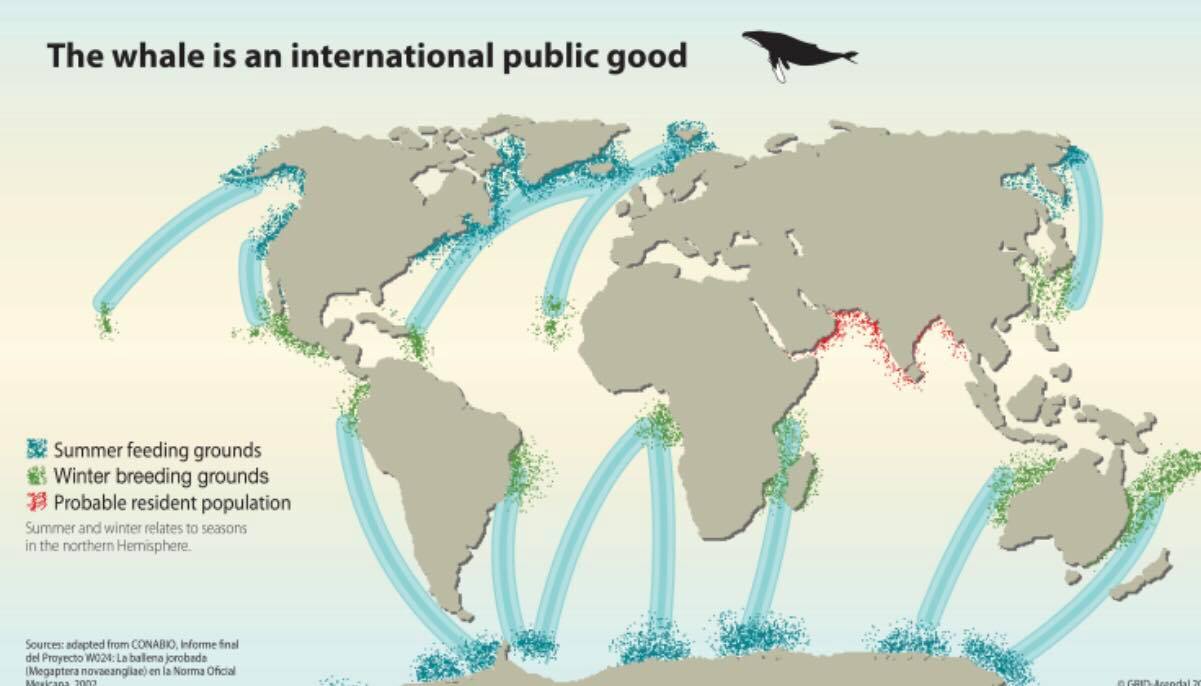

In addition, whales are fertilisers of the ocean and provide nutrients, namely iron and nitrogen for phytoplankton growth, tiny microscopic marine algae. Phytoplankton are responsible for at least 50% of all oxygen added to our atmosphere. In recent years scientists have discovered that whales help to promote phytoplankton growth through what is known as the "whale pump" Whales bring nutrients to surface waters through vertical movements and through their migration routes travelling across ocean basins, i.e. the "whale conveyor belt". Preliminary modelling has shown that this fertilising activity adds to phytoplankton growth rates in are where whales are frequent.

If whale populations were allowed to rebounded to pre whaling numbers it could add significantly to the amount of carbon that could be captured and phytoplankton produced in the oceans. Minimum estimates indicate that even a 1% increase in phytoplankton productivity thanks to the presence of whales could capture hundreds of millions of tons of additional CO2 every year, equivalent to the appearance of 2 billion mature trees. This could have a massive impact over the lifespan of a whale, which is over 60 years.

Despite the global ban on commercial whaling, some countries such as Iceland, Norway and Japan still hunt whales, and whales face many other threats from human activities including from ship strike, by-catch and entanglement in fishing gear, plastic and noise pollution. While some species such as humpback whales in the Southern Hemisphere are recovering, slowly, many others are not.

When we look at it from an economic perspective, protecting whales has a cost, but so too does not protecting them. Determining a whale's monetary value therefore becomes important for engaging business, governments and individuals around the world.

Whales provide eco-system services that benefits people all over the world, and can therefore be classed as a "public goods". In other words, whales are afflicted with the classic "tragedy of the commons", whereby no individual who benefits from them is sufficiently motivated to contribute to supporting their conservation. To solve this issue, we must address the monetary value of a whale, by showing business and interested stakeholders that the benefits of protecting whales far out-weigh the costs. The current stocks of great whales have been valued at over 1 trillion U.S. dollars, or 2 million/whale based on their sequestered carbon over a lifetime, using the market price for carbon dioxide, and adding their other economic contributions such as eco-tourism and fisheries.

As we are facing the climate crises here and now, it is important we take active measures to provide more adequate protection for the great whales, with no haste in identifying and implementing new methods to prevent or reverse harm to global marine ecosystems. This is of particular importance if we want our whale populations to grow more rapidly. Unless urgent action is taken now, it is estimated that it could take over 30 years for whale population numbers to double and several generations to return to their pre-whaling numbers. This is time we cannot afford to loose.

© Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and www.orcireland.ie , est. 2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland and www.orcireland.ie with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

References:

Lavery, T., B. Roudnew, P. Gill, J. Seymour, L. Seuront, G. Johnson, J. Mitchell, and V. Smetacek. 2010. “Iron Defecation by Sperm Whales Stimulates Carbon Export in the Southern Ocean.” Proceedings of the Royal Academy

127:3527–31.

Lutz, S., and A. Martin. 2014. “Fish Carbon: Exploring Marine Vertebrate Carbon Services.” Blue Climate Solutions report, The Ocean Foundation, Washington, DC.

Pershing, A., L. Christensen, N. Record, G. Sherwood, and P. Stetson. 2010. “The Impact of Whaling on the Ocean Carbon Cycle: Why Bigger Was Better.” PLoS One 5 (10): 1–9.

Roman, J., J. Estes, L. Morissette, C. Smith, D. Costa, J. McCarthy, J. B. Nation, S. Nicol, A. Pershing, and V. Smetacek. 2014. “Whales as Marine Ecosystem Engineers” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12 (2): 377–85.

Smith, C., J. Roman, and J. B. Nation. 2019. “A Metapopulation Model for Whale-Fall Specialists: The Largest Whales Are Essential to Prevent Species Extinctions—The Sea.” Under review.

www1: www.imf.org.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE