OVER 300 SPECIES OF SHARKS ARE THREATENED WITH EXTINCTION!

Sophie A. MayCock | 6th of February 2021.

New assessments by the IUCN show 316 (shark, skate, ray, and chimera) species are now threatened with extinction (WWF, 2020).

‘Endangered’ is a term we hear often on nature documentaries or in the news. Even if you don't understand the details about how a population is assessed, you are probably aware that there is a very serious situation when scientists consider a species to be endangered. In the past few months, extremely alarming headlines have made the news regarding how many species of sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras (collectively known as ‘chondrichthyans’) are considered to be endangered. A report by

The International Union for the Conservation ofNature (IUCN) has shown that more than 300 species ofchondrichthyans should be re-classified as endangered. Scientists now say that the chondrichthyans are at substantially higher risk of extinction compared together groups of animals, like mammals or birds. But what does this mean for sharks? And is there any hope? Will we lose all of these wonderful species forever or can we turn it around?

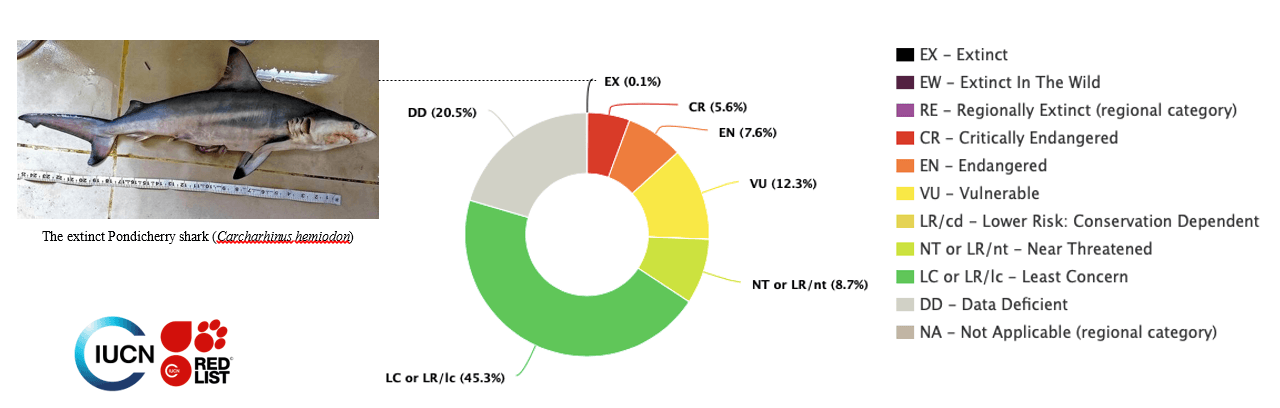

The IUCN produces

The Red List of Threatened Species , which categorises plant and animal species into different tiers of concern based upon how great their risk of extinction is:

‘vulnerable’ (VU),

‘endangered’ (EN) or

‘critically endangered’ (CE) being the most alarming classifications for an extant species. Some species are considered

‘data deficient’ (DD) or

‘not evaluated’ (NE). This means that there has not yet been enough work to determine the status of the population in the wild and the IUCN will strive to prioritise their assessment. When a species is considered

‘extinct in the wild’ (EW),this means that there are only some individuals left in captivity, and

‘extinct’ (EX) means there are none left alive at all and the species is considered lost forever.

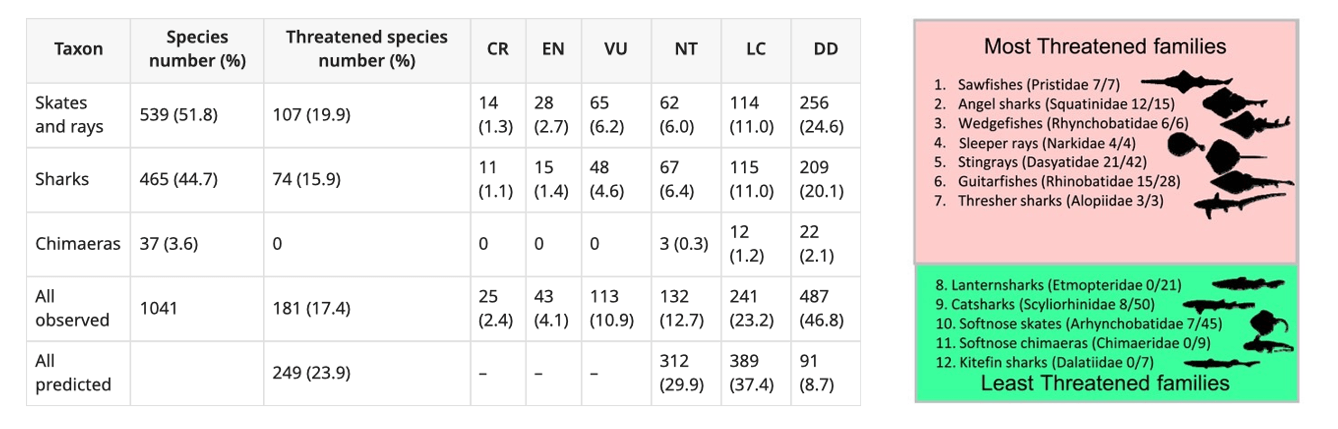

In 2014, a landmark paper produced for the IUCN assessed the populations of more species of chondrichthyans than had ever been achieved before. A remarkable effort, but with dire findings. The scientists discovered that 25% of the 1,041 known species of chondrichthyans should be considered threatened according to the criteria of the IUCNRed List. Scientists had found that around 20% were at risk of extinction, with at least 14 species of sharks, skates and rays falling into the critically endangered category.

That was horrifying… but the most recent report produced by the IUCN (at the end of 2020), has gone even further.In 420 assessments covering 1,134 species of chondrichthyans, the IUCN has now managed to sufficiently evaluate many

‘data deficient’ species, to determine their level of threat. Once again, this is a remarkable achievement, but again, we were met with alarming findings. Today, 154 species of chondrichthyan fishes are considered to be at risk of extinction. Of these, 37had never been assessed by the IUCN before. This means that species are at risk of dying out before scientists have even had an opportunity to study them properly! Sadly, the IUCN also concluded that several species of sharks and rays should already be considered extinct, including the Pondicherry shark (Carcharhinus hemiodon).

“

Sharks and their relatives are facing an alarmingly elevated risk of extinction

”

- Dr Nick Dulvy, IUCNShark Specialist Group Co-Chair

The report also reclassified several species; amping up their extinction risk. For example, the tope shark(Galeorhinus galeus) was reclassified up from vulnerable to critically endangered (skipping the endangered category altogether). This species is now at the highest level of extinction risk, as populations of tope are considered to have declined by as much as 88% globally, in just 80 years.

Furthermore, the report also documented that certain taxonomic groups within the chondrichthyans were worse off than others: rays like the guitarfish (Family

Rhinobatidae ) and wedge fish (Family

Rhinidae ) were found to be significantly more threatened than sharks. Yet, certain groups of closely related sharks were also considered to be particularly at risk: the angel sharks (Family

Squatinidae ) and hammerheads (Family

Sphyrnidae )now have a disproportionate number of their members listed by the IUCN, so they are considered to be the most threatened families of sharks (IUCN, 2020).

It all sounds pretty dire, doesn't it? Yet, we must refuse to give up on these animals!

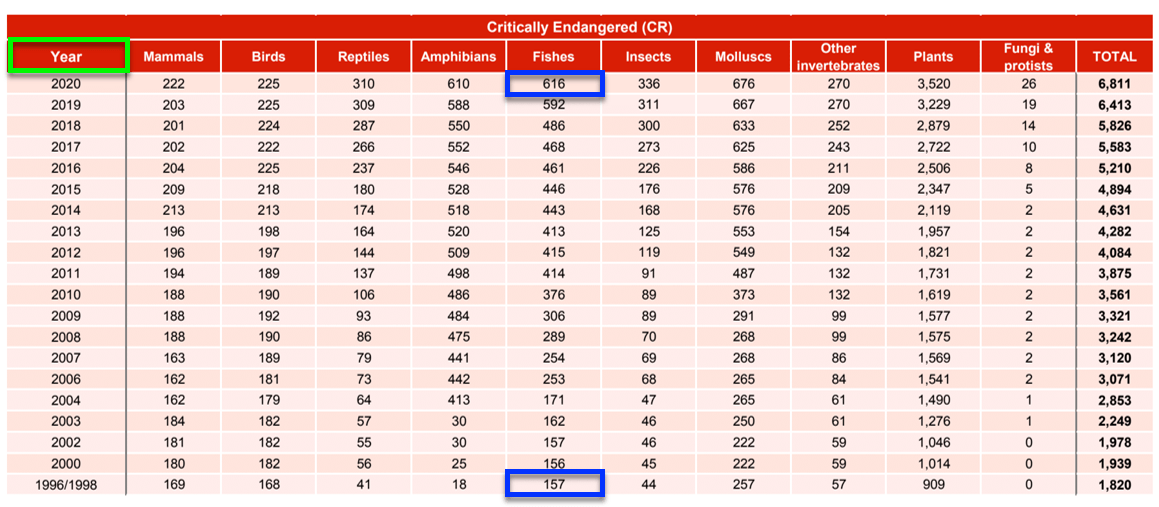

One glimmer of hope comes in knowing that, as the IUCN continues to do its incredible work, and classifies more and more species, inevitably we will see more species added to the Red List (I know that sounds backwards, but bear with me!). If you study the IUCN report’s table detailing how many species of different animals are classified as critically endangered throughout time(below), you will see 616 fishes in 2020, where there were only 157 species in1996. This is not necessarily because as time marches on more species are actually becoming threatened with extinction, but because we have reduced the number of species which are data deficient and have not been assessed. In fact, these species could potentially have been threatened for some time, but we just didn’t know about it (this is known as a “sampling bias”).

Another ray of light comes with how much work is now being carried out to protect sharks and rays. The IUCN has formed an expert panel called the Shark Specialist Group (SSG), devoted to assessing global population trends and making conservation recommendations to decision-makers. And there are many, many other groups around the world working on scientific research and fighting to improve shark and ray management. The plight of these animals is far better understood now, even compared to just a few years ago and the general public is also rallying be hind the cause.

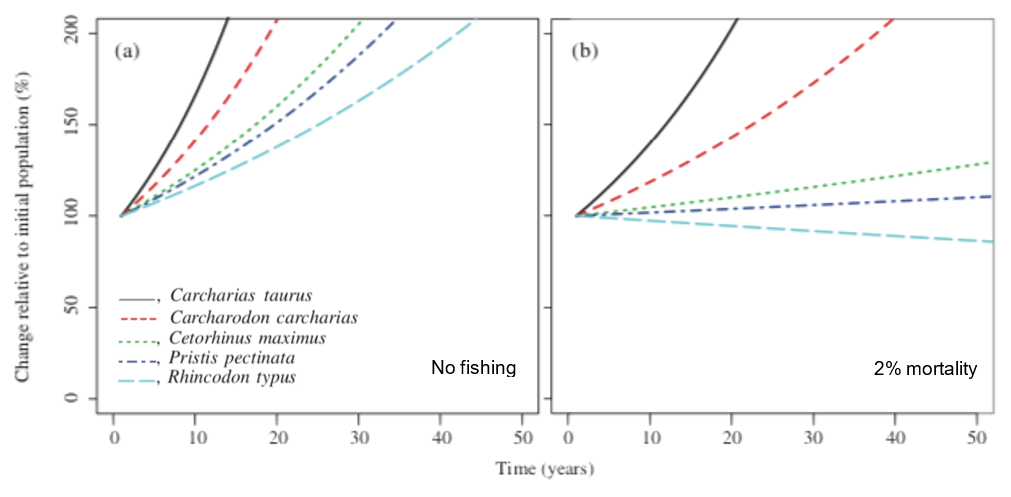

Because conservation initiatives for sharks and rays CAN be successful! For instance, one scientific paper predicted that populations of several different species of sharks could certainly begin to rise if strict conservation measures were introduced to protect them. Using advanced statistical models, they showed that four of the five shark populations they assessed would begin to increase within just 10 years of protective measures being introduced. Yet, they also emphasised that a one-size-fits-all-strategy would be likely to fail, as each species has a different rate of recovery. This is because different species grow andreproduce at different rates. For instance, the ragged tooth sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus) showed great promise of rapid recovery, whilst whale shark (Rhinocodon typus) populations would require tighter controls and would be slower to increase after protection (more than 50 years!).

They concluded that a multi-facetted approach would be necessary to ensure that conservation measures for sharks would be affective. They advised that simultaneously reducing the amount of shark fishing that is allowed, creating shark sanctuaries (where no fishing is allowed to take place at all) and restoring critical habitats (like nursery and feeding grounds) would give sharks a fighting chance.

“Recovery of elasmobranchs is certainly possible

but requires time and a combination of strong and dedicated management actions to be successful”

- Ward-Paige

et al. (2012)

The scientists also emphasised that public education would be critical to ensuring success. It is the passion (or outrage) from the public that forces governments and industry into making difficult (and potentially expensive) decisions. If more people voice their concern for endangered sharks and push for better conservation, then together, we will be able to put pressure on decision-makers! And this starts with each and every one of us!

To add your voice to the fight for shark conservation, you can join: ORCAIreland and support our

Shark Research ! Visit orcaireland.org to help us to encourage best practices for shark angling in Ireland and to promote citizen science among the angling and diving community to help us monitor these important key stone species that are now threatened with extinction! You can also wear an Exclusive ORCAIreland Shark T-shirt and support our work by visiting

orcashop.teemill.com.

References:

Dulvy, N.K., Fowler, SL., Musick, J.A., Cavanagh, R.D.,Kyne, P.M., Harrison, L.R., Carlson, J.K., Davidson, L.N.K., Fordham, S.V., Francis, M.P, Pollock, C.M., Simpfendorfer, C.A., Burgess, G.T.H., Carpenter, K.E., Compagno, L.J.V., Ebert, D.A., Gibson, C., Heupel, M.R., Livingstone, S.R., Sanciangco, J.C., Stevens, J.D., Valenti, S., White, W.T. (2014). Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks andrays.

eLife , 3:e00590, DOI:

10.7554/eLife.00590

. Access online:

https://elifesciences.org/articles/00590

.

IUCN. ( 2020 ).The International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red list of ThreatenedSpecies Annual Report.

Ward-Paige, C.A., Keith, D.M., Worm, B., Lotze, H.K. ( 2012 ). Recovery potential and conservationoptions for elasmobranchs.

Journal of Fish Biology ,

80 , 1844–1869. Access online:

https://whitesharkconservationtrust.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Recovery-potential-and-conservation-options-for-elasmobranchs.-2012.-C.-A.-Ward-Paige-D.-M.-Keith-B.-Worm-H.-K.-Lotze.pdf .

#GlobalSharkTrends