ORCAS IN IRISH OCEANS!

ORCAs in Irish Oceans

ORCA Sci-Comm Team | August 22nd, 2018.

Éire is a an island situated in the north-east Atlantic Ocean, with a marine territory ten times the size of the lands, surrounded by cool temperate waters, from shallow continental shelf slopes to deep abyssal waters, such as the Rockall Trough. The oceans of Éire play an important role in the overall healthy functioning of the Atlantic Ocean, and a diverse range of marine top-predators or keystone species, such as cetacean’s, elasmobranchs, pinnipeds and seabirds, use Irish waters as important foraging and reproductive habitat.

Of late, 25 species of cetaceans have been observed in the oceans of Éire. A diverse array of cetacean species have been recorded, some residents, such as the bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus ) in the Shannon Estuary, Co. Clare, and others are migratory/seasonally occurring species, such as the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeanglia ) which during the autumn can be seen in Irish waters and undergoes large scale movements in distribution, using the south and west coasts as important “stop off’s”, in times when their preferred prey, herring (Herrangus herrangus) and sprat (Sprattus sprattus) are abundant. Other cetacean species such as the killer whale (Orcinus orca) can also be seen in Irish waters occasionally.

The latin name Orcinus translates as "belonging to Orcus", who was the Roman god of the netherworld. Orca translates to "large-bellied pot" but orc - also refers to a whale.

Killer whales or “orcas” are a world-wide recognisable odontocete species, with which we often associate with waters of the west coast of Canada, B.C or the shores of New Zealand. In fact, orcas are closer to home than we may think, in more ways than one.

Orcas are extremely intelligent, have tight-knit familial social bonds, and have the largest distribution of all marine mammals. This cosmopolitan dolphin’s range expands to all temperate and tropical waters, however, the greatest abundances in the north-east Atlantic can be found in colder waters in the Arctic, such as Norway and Iceland. Orca whales have nomadic life strategies, their distribution is determined by that of their prey and some have home ranges as large as 1000 km2. They generally travel at speeds of 5 knot, covering up to 2 km a day.

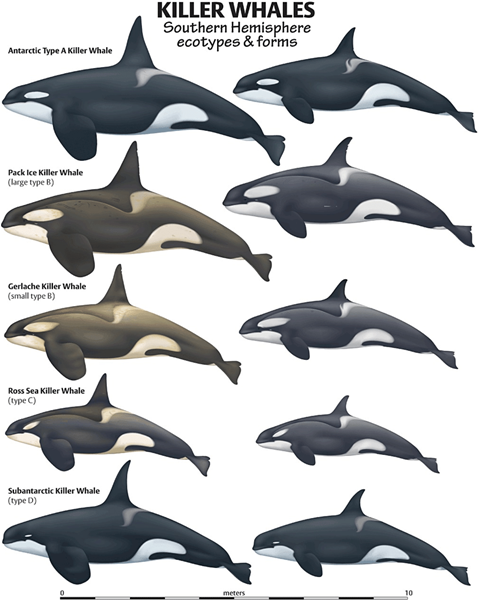

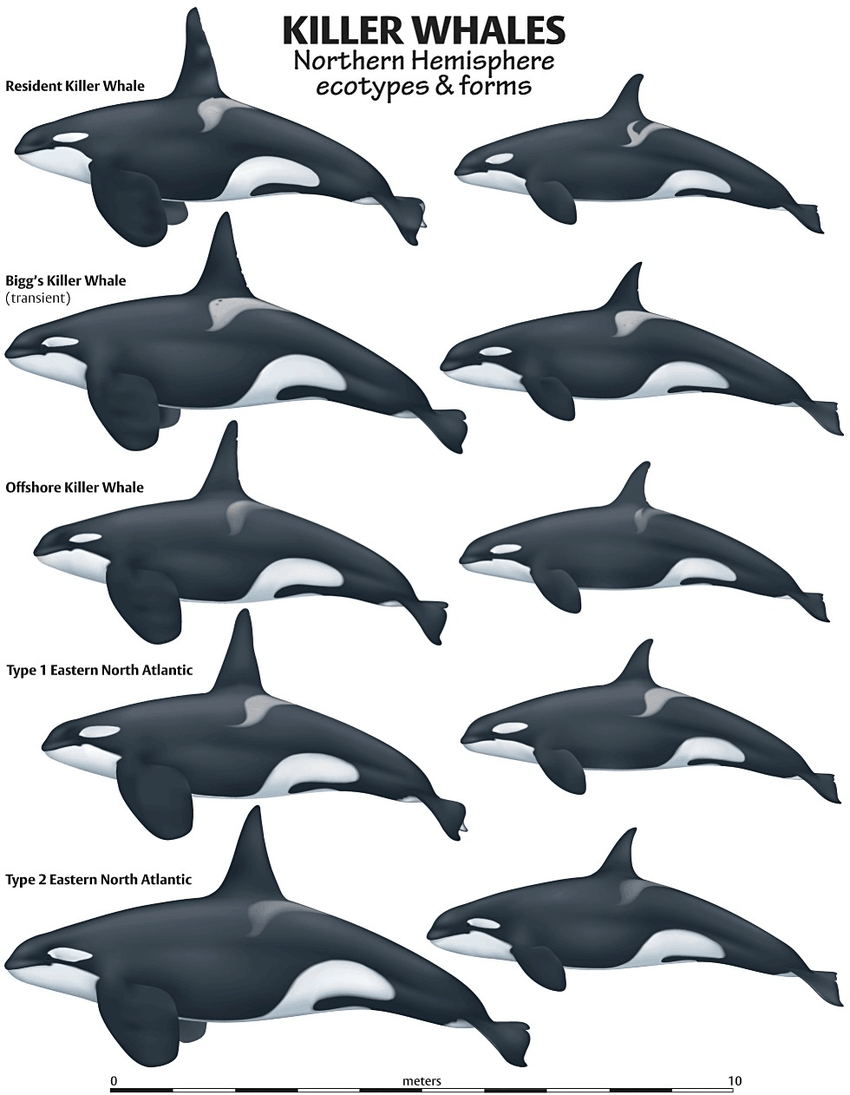

Recent research has revealed five ecotypes of killer whales in the Northern Hemisphere and five more from the southern hemisphere, based on the evolutionary mechanisms of the horizontal and vertical transmission of culture through learned behaviour such as foraging strategies and acoustic communication, that have resulted in reproductive isolation, even in sympatry and led to speciation as a result of dietary specializations.

TYPE A- Antarctic

Large pelagic orcas (up to 9.5m) found in the Southern Ocean and primarily hunt minke whales, ( Balaenoptera acutorostarta ), following their migration in and out of Antarctic waters.

TYPE B - Pack Ice

Large orcas that hunt seals along loose pack ice in the Antarctic. Renowned for their cooperative wave-washing hunting technique, where they use their tails and bodies to create waves to wash seals off ice sheets.

TYPE B- Gerlache

Named for the Gerlache Strait of the Antarctic Peninsula where they are most frequently observed, thse orca are smaller than Type A and Pack Ice orcas. Their diet preferences are unknown, but they have been seen feeding on penguins and are usually spotted around penguin colonies.

TYPE C- Ross Sea

Ross Sea orcas are the smallest ecotype of killer whale at 6m long. Previous sightings have been off Eastern Antarctica in thick pack ice. Ross Sea orcas have been seen eating Antarctic toothfish, however, it is still unknown if they specialize only on fish.

TYPE D- Sub-Antarctic

The most recently discovered ecotype was found in the 1950's in a mass stranding event in New Zealand. Subantarctic killer whales share the black-and-white coloring and saddle patch patterns of other orcas, however have shorter dorsal fins, rounder heads, and the smallest eye patches of any ecotype, giving them a very distinctive appearance. Since their discovery there have only been a handful of sightings of this rare ecotype. They have been seen consuming Patagonian toothfish, but like the Ross Sea orcas, it is still unknown if they are fish specialists.

In December 2017, Scientist Dr. Conor Ryan, originally from Cork, was part of a research team on-board the National Geographic's Linblad Expeditions, and were the first to capture underwater footage of type D killer whales;

Northern Hemisphere Killer whales

RESIDENT

Resident orcas are fish-specialists, and have small home ranges around areas of large fish populations. Residents are found on both sides of the North Pacific; the Northern and Southern communities almost exclusively hunt salmon, while Residents in Alaska appear to be more generalist in their fish preference, eating multiple fish species including salmon, mackerel, halibut, and cod.

BIGG’S

Bigg’s, or transient, orcas are also found in the North Pacific. These are mammal-eating whales, and like Residents, different communities of Bigg’s orcas specialize on different prey – from harbor seals ( Phoca vitulina ) to minke whales to gray whale calves. They live in small groups and travel frequently over large home ranges, from Southern California up to the Arctic circle.

OFFSHORE

Little is known about the offshore ecotype found in the North Pacific as sightings of them are rare due to their distribution being mainly over the outer continental shelf. Their large range stretches from Southern California to the Bering Sea, and their social structure and prey preferences are still unknown.

TYPE 1

Type 1 Noth Atlantic orcas are generalist foragers. relatively small and live in closely related pods. They are known to feed on large runs of herring and mackerel around Norway, Iceland, and Scotland; and some have been seen hunting seals as well. Like other orca ecotypes, different communities have different prey preferences and have different home ranges. Type 1 orcas off Norway have been observed using a carousel feeding technique, herding herring into dense balls, then slapping with their tails to stun the fish. Research on Type 1 orcas is ongoing, and photo-identification studies are gradually revealing the size and population structure of these orcas; they may be more divided into separate populations than previously thought ( https://www.norwegianorca-id.no/ ).

TYPE 2

Type 2 North Atlantic orcas prey primarily on other whales and dolphins, particularly minke whales. They are large orcas with distinctive back-sloping eye patches. Similar to the different ecotypes in the Pacific, the prey specializations of Type 1 and Type 2 orcas are reflected in their teeth – Type 1 orcas have very worn teeth from feeding on fish, while Type 2s have larger and sharper teeth for hunting other mammals.

In Ireland, larger groups of orca have been spotted offshore in deep waters over the continental shelf and have been seen by offshore islands, such as the Blasket Islands, Co. Kerry, Cape Clear, Co. Cork, the Saltee Islands, Co. Wexford, Achill Island, Co. Mayo and the Inishowen Peninsula, Co. Donegal which offer an excellent opportunity for sightings of cetaceans from the shore.

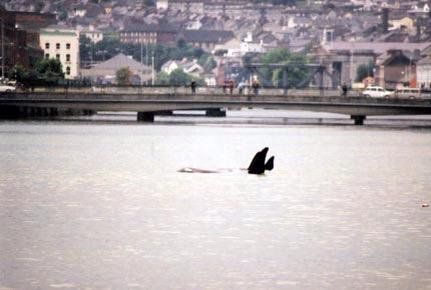

The first reported sighting of an orca in inshore Irish waters was in 1977, in Lough Foyle, Co. Derry, during the end of the salmon ( salmo salar ) run. The killer whale stayed foraging in the lough for two days and was reported to travel west along the coast of Donegal.

Between June and September 2001, a group of killer whales took up summer/autumn residence in Cork harbour, feeding on salmon and mullet, and were reported swimming up the River Lee, into the city centre.

From 2009 onwards, there was an increase in sighting reports of this apex predator in Irish waters, but the recent trends suggest sightings have decreased again since 2013. Photo identification analysis carried out by the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group indicates that the majority of sightings are of individuals from the Scottish West Coast Community, a group of eight adults which generally reside in the Scottish Hebridean Islands. In recent years, individual bull males and groups have been reported along the west coast. Since 2004, re-sightings of well-marked individuals such as “John Coe” (#001) and “Floppy Fin” (#002) have also been reported.

At the end of June 2010, two orca were sighted, 10 miles south-west of Skellig Michael. In July 2012, just east of the Wild Bank, in Dingle Bay, “John Coe” and his mother “Nicola” were spotted. In September 2014, a pod of seven killer whales were spotted from the deck of the Marine Institutes, R.V Celtic Explorer off the south-west coasts of Ireland. “John Coe” was last spotted off Clogher Head, Co Kerry in June 2016 and most recently, on the morning of the 5th of March 2018, with another large male bull “Aquarius” in the same area travelling south.

After a cold spell of extreme weather with "Storm Emma", Nick Massett, along with other whale enthusiasts Simon Crompton and Britta Wilkins out on the first sign of ideal whale-watching conditions in the hopes of catching a glimpse of some cetaceans. Nothing could have prepared them for this magnificent encounter!

Just one week beforehand, these whales were seen off the north coast of the Isle of Mull ( https://hwdt.org/news/2018/2/26/killer-whale-alert-john-coe-and-friend-spotted-off-north-coast-of-mull ). UCC Researcher and PhD candidate Róisín Pinfield estimated that the pair travelled a distnace of 338nm or 625 km in 7 days ( https://www.facebook.com/KillerWhaleResearchIreland/photos/pcb.2048251232119133/2048247538786169/?type=3&theater ).

“John Coe” was first photographed off the Scottish Hebridean Islands in 1983 by Peter Evans. With more regular occurrence of killer whales in Irish waters concerns exist over orcas prey availability and the fact that the group have not reproduced in over two decades.

Orcas feed on a diverse array of prey species from fish to marine mammals, pinnipeds and small cetaceans such as the harbour porpoise ( Phocoena phocoena ) and elasmobranchs. Killer whales in Irish waters are predominantly fish eaters and have been found to follow herring and mackerel trawlers offshore ( https://www.facebook.com/KillerWhaleResearchIreland/ ). However, the trend in re-sightings of individuals from the west coast community at the Blasket Islands, Ireland’s largest grey seal ( Halichoerus grypus ) breeding colony may indicate these whales may be hunting seals in Irish waters. Furthermore, killer whales from the Scottish West Coast have been shown to also harass and kill harbour porpoise and minke whale ( Balaenoptera acutorostrata ).

The Scottish west Coast Community of Killer whales face a number of threats, particularly due to the critically small population size. Previous studies have found a high pollutant burden in Killer whales stranded on Irish shoes and 10% of whales and dolphins were found to have plastcs in their stomachs (Lusher et al ., 2017) and it is thought this may be a significant contributor to the lack of juvenile recruitment, as being apex predators, bioaccumulation of toxic compounds may have led to infertility in the small population. Bioaccumulation of radioactive isotopes from radioactive waste by power stations dumped at sea has been shown in a number of marine top predators such as shark, blue-fin tuna and swordfish. Pollution from plastics such as PCB's can also bioaccumulate up the food chain.

On a Global scale, killer whales are showing speciation into two separate species, where isolated populations have evolved separately, in comparison to gradual co-evolution of a species and the clue is in their teeth!

Killer whales stranded on Irish shores have flat worn teeth, typical of herring and sprat-eating whales, who use these spade-like teeth to crunch fish bones. Marine Mammal eating killer whales have large sharp teeth with serrated edges for cutting through tough meat, blubber, and sea mammal bone.

The best time to see killer whales in Irish waters, based off the above data is off the coast of Kerry in mid June- mid July, and any time after that until the end of October.

Now you can become a citizen scientist and Download the “ORCA Ireland Observers App for Free on Google Play for Android or make a report directly on our website in "Home" -> "Make a report".

Sign up for FREE via the member's tab and access all our social media from one place, browse our gallery and videos, and report sightings of whales, dolphins, octopus and sharks caught angling. Check out the free education tab powered by Khan Academy- search "biodiversity" and enhance your knowledge.

©Ocean Research & Conservation Association Ireland (ORCAIreland) and www.orcaireland.ie , est. 2017. Un-authorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to ORCAIreland and www.orcaireland.ie with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE