Whales that Walked on Land - A new amphibious whale discovered in Egypt.

EMER KEAVENEY | 4th September 2021

A new discovery of an amphibious whale that walked on land has been named after the Egyptian god of death and mummification, - 'Anubis'. Scientists have discovered the skeleton of a whale that lived 43 million years ago in the Fayum region of Egypt, on both land and in the sea.

Cetacean Evolution:

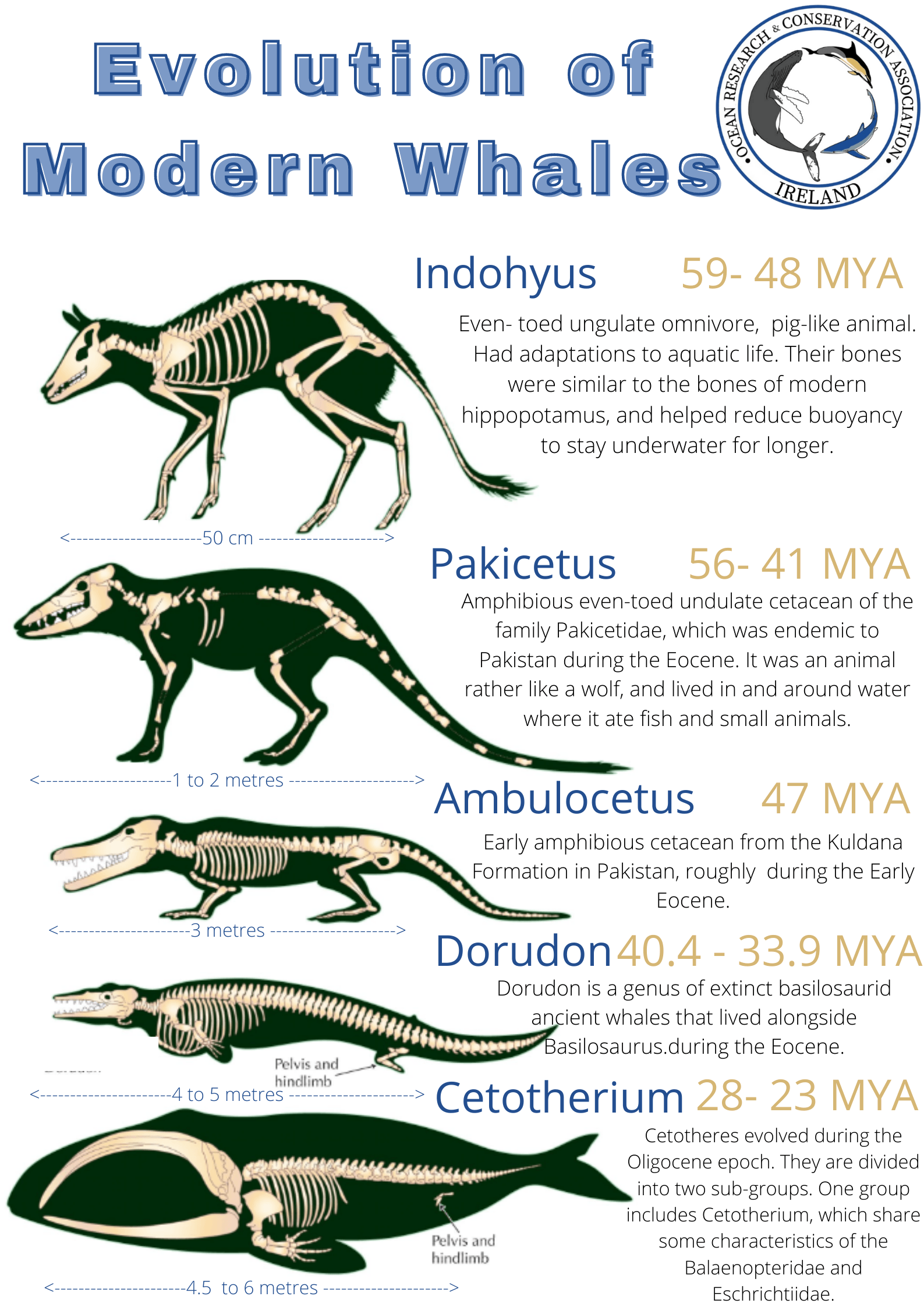

Fossil records of large marine mammals; dolphins and whales, of the monophyletic order Cetacea, date back to 45 million years ago (MYA), during the middle Eocene. While the majority of research on Cetacea to date, focus primarily on extant (living) species ecology, population dynamics and behaviour, much focus has also been given to evolutionary studies which extrapolate from modern Cetacea and interpret fossilised specimens.

Modern cetaceans are have morphological and physiological adaptations to allow them to live in fully aquatic environments. The body is streamlined with paddle-shaped forelimbs, no external hind-limbs, and they have horizontal tail flukes. Early primitive toothed Cetacea, the archaeocetes, arose from terrestrial mammals, which possibly exploited shallow marine food reserves. Archaeocetes had distinctive aquatic adaptations: including:

- Elongated jaws, associated with an active predatory habit;

- Typically the cetacean ear was coupled acoustically with seawater, and probably functioned in underwater intra-specific communication and possibly food detection.

- Underwater vision, in the inferred absence of sonar or underwater olfaction, probably was the prime sense used in hunting; the forelimbs are flat and paddle-like, and hind-limbs reduced.

- The tail could be flexed dorsoventrally.

However, some remnants of archaeocetes terrestrial heritage remained. For example, the olfactory system is well developed, and perhaps was important in aerial intraspecific communication, and archaeocetes body structure does not preclude (phocid) seal-like movement in shallows or on land. Unlike seals which give birth on land, cetaceans are fully aquatic and give birth in the sea. However, modern baleen and toothed whales differ greatly to extinct archaeocetes in many ways. One notable difference is in feeding ecology, which is reflected in skull structure.

New Whale Species:

A recent study published in the

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Publishing

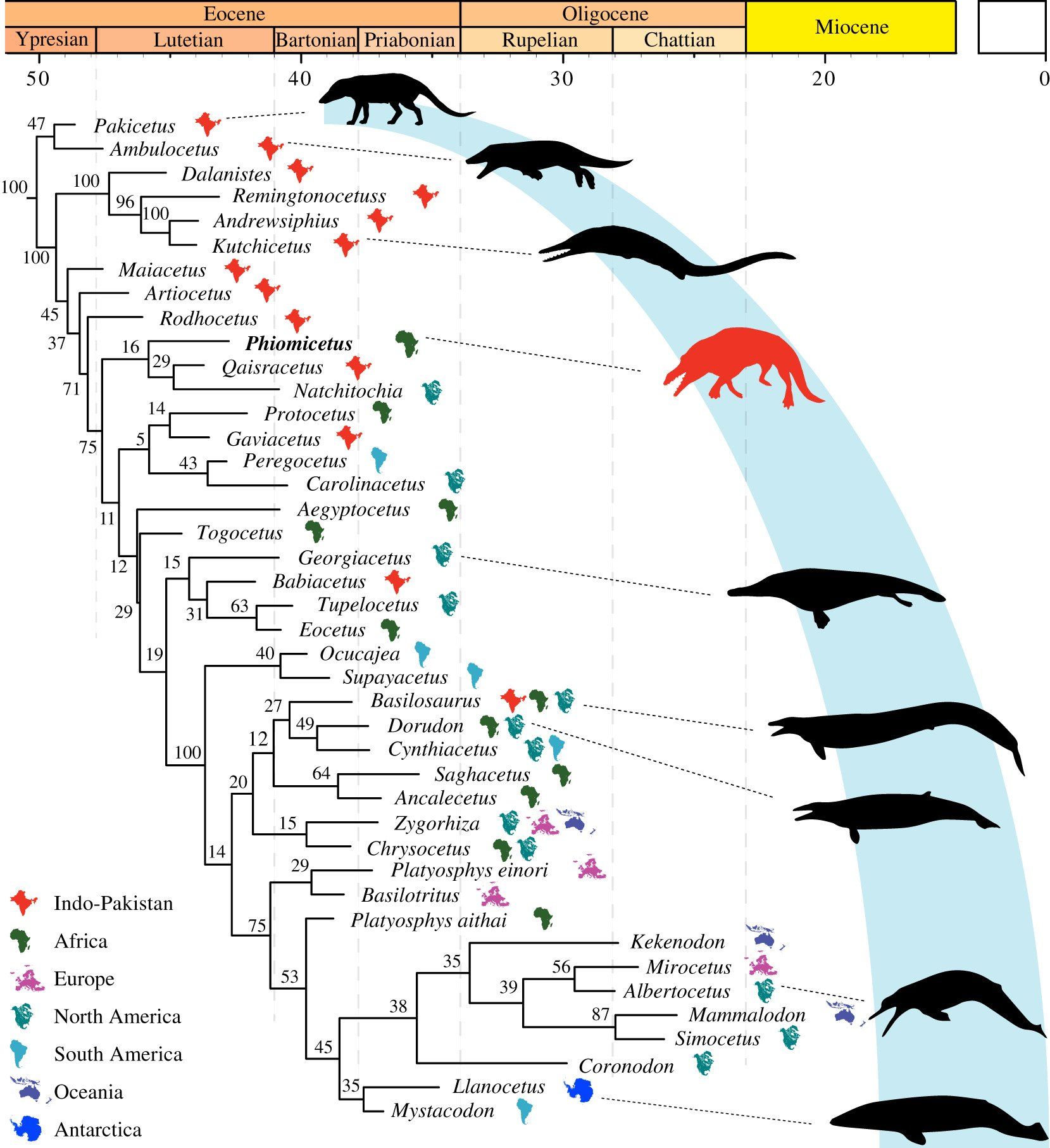

describes a newly discovered fossil of a previously unknown whale species — one that had four legs and a powerful, raptor-like jaw. Over a period of approx. 10 million years, the ancestors of whales evolved from herbivorous, deer-like, terrestrial mammals into carnivorous and fully aquatic cetaceans. Protocetids were early ancestors of modern whales from the Eocene that represent a unique semiaquatic stage in that dramatic evolutionary transformation.

The newly discovered medium-sized protocetid, (Phiomicetus anubis), consists of a partial skeleton from the middle Eocene, 43 million years ago (MYA), of the Fayum Depression of the Egyptian Western Desert. The Fayum area is not only famous for prehistoric whales; it is also an important region for Palaeogene fish, sharks, and land mammals.

Morphology:

Based on a comparison of cranial measurements for

P. anubis

with other protocetids, it was estimated to have been approx. 3 metres in length and weighed ca. 600 kg in life. Although it was a large semi-aquatic animal, the presence of high neural spines on the anterior thoracic vertebrae is a feature common in land mammals that is found in protocetids and distinguishes these species from basilosaurids.

Feeding Ecology:

The most notable anatomical features of

P. anubis

are associated with its foraging ecology. One of the key features seen in the cranium is the enlarged temporal fossa, occupied by relatively large muscles of mastication with larger cross-sectional areas and increased capacity for powerful bite force, presumably representing an adaptation for raptorial feeding on larger prey.

Dental wear, strongly resembles that of modern pinnipeds (seals) and to a lesser extent odontocetes, such as killer whales (Orcinus orca). Tooth wear of

P. anubis

suggests that it had both a piscivourous and carnivorous diet, with teeth being used for prey capture of large, armoured fish/sea turtles, sharks and smaller cetaceans. They further suggest that prey items were usually too large to be swallowed whole and had to be sheared into smaller parts.

P. anubis

used the same mechanism that modern crocodilians and sharks use in hunting large prey items (e.g. large fish or small cetaceans) by pulling them onto land or tearing them by seizing a part of the prey with powerful jaws then rolling and twisting the entire body.

Habitat:

Echinoids found in the middle part of the Midawara Formation, of the Fayum Depression, suggests a carbonate marine environment, indicating coastal marine waters with no freshwater influence, however

P. anubis

was discovered in the green shale, suggesting a more deep-water environment. This confirms quite a high degree of dispersal ability early in cetacean evolution, and raises new questions about early cetacean biogeography. it also highlights the prospect that further exploration in Egypt and in Africa, may uncover even more primitive archaeocetes and provide an important test of the hypothesis that basal archaeocetes were restricted to Indo-Pakistan.

REFERENCES:

Barnes, L. G. and Mitchell, E. D., (1978). Cetacea. In: V. J. Maglio and H. S. B. Cooke (Editors), Evolution of African Mammals. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp. 582--602.

Edinger, T., (1955). Hearing and smell in cetacean history. Monatsschr. Psychiatr. Neurol., 129: 37--58.

Fordyce, R. E. (1980). Whale evolution and Oligocene southern ocean environments. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 31, 319–336. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(80)90024-3.

Gohar AS, Antar MS, Boessenecker RW, Sabry DA, El-Sayed S, Seiffert ER, Zalmout IS, Sallam HM. (2021) A new protocetid whale offers clues to biogeography and feeding ecology in early cetacean evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 288: 20211368. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.1368.

Kellogg, A. R., (1936). A review of the Archaeoceti. Carnegie Inst. Wash., Publ., 482: 366 pp.

Norris, K. S., (1968). The evolution of acoustic mechanisms in odontocete cetaceans. In: E. T. Drake (Editor), Evolution and Environment. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., pp. 297--324.