New Branch on the Tree of Life Discovered by Canadian Scientists

Researchers in Canada have made the discovery of a lifetime- a new kind of organism that is unlike any other recorded before. It is so different that it does not fit into the plant kingdom, the animal kingdom, or any other kingdom which scientists use to classify known organisms.

A new report this week in the journal Nature has revealed through genetic analysis, newly discovered microbes that represent a completely new branch on the tree of life. The discovery was made by graduate student Yana Eglit, of Dalhousie University, in an opportunistic sample of soil collected while on a hike in Nova Scotia, Canada.

"They represent a major branch… that we didn't know we were missing," said Dalhousie biology professor Alastair Simpson, Eglit's supervisor and co-author of the new study.

"There's nothing we know that's closely related to them."

In fact, he estimates you'd have to go back a billion years — about 500 million years before the first animals arose — before you could find a common ancestor of hemimastigotes and any other known living things.

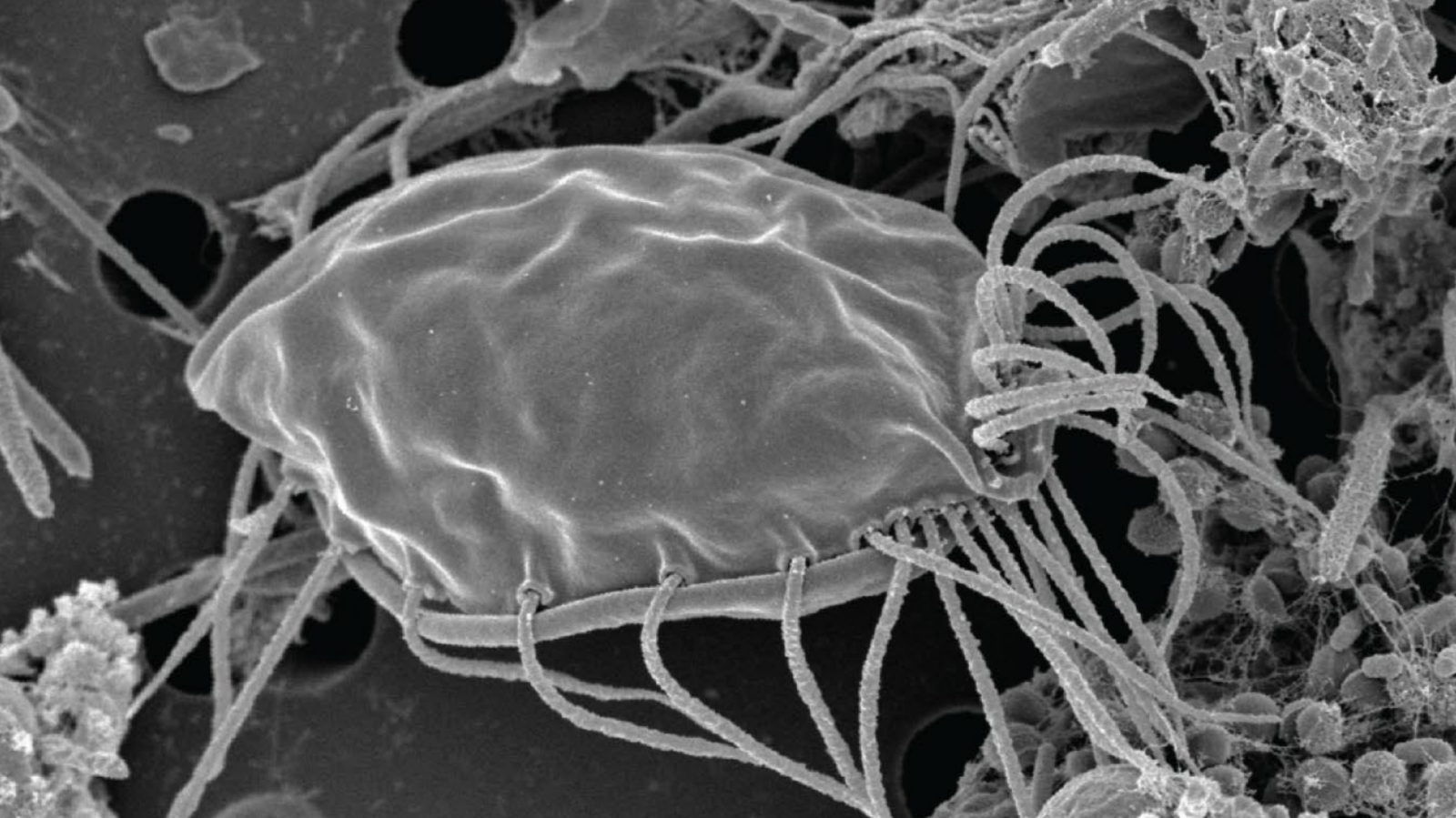

The microbes were discovered along the Bluff Wilderness Trail outside Halifax a couple of years ago. After three weeks during analysis of the soil sample, Eglit noticed something unusual-something shaped like the partially opened shell of a pistachio. It had lots of hairs, called flagella, sticking out. Most known microbes with lots of flagella move them in co-ordinated waves, but not this one, which waved them in a more random fashion.

Hemimastigotes were first seen and described in the 19th century. However, at that time, no one could figure out how they fit into the evolutionary tree of life. Consequently, they've been "a tantalizing mystery" to microbiologists for quite a long time.

Similar to animals, plants, fungi and amoebas — but unlike bacteria — hemimastigotes have complex cells with mini-organs called organelles, making them part of the "domain" of organisms called eukaryotes rather than bacteria or archaea.

Over the last century, 10 species of hemimastigotes have been described but up until now, no one had been able to do a genetic analysis to see how they were related to other living things.

To the researchers surprise, two species of this rare microbe ended up in the same petri dish and it turned out one of these species was also newly described. They named it Hemimastix kukwesjijk after Kukwes, a greedy, hairy ogre from the mythology of the local Mi'kmaq people. (The suffix "jijk" means "little."

H. kukwesjijk is a predatory microbe and shoots little harpoons called extrusomes to capture prey such as Spumella, a relative of aquatic microbes called diatoms. It grasps its prey by curling its flagella around it, bringing it to a "mouth" on one end of the cell called a capitulum "as it presumably sucks its cytoplasm out," Eglit said.

The team is continuing genetic analysis of Hemimastix, having successfully "domesticated" the microbe, breeding it under laboratory conditions, relieving the issue of it's rarity. Further analysis is expected to turn up new data that will help scientists piece together the evolutionary history of life on Earth with more detail and more accuracy.

This new discovery of an organism unlike any other known lifeform on Earth, exacerbates how little we still know and how important it is that we protect natural habitats for future discoveries.

© Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and www.orcireland.ie , est. 2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland and www.orcireland.ie with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE