Mako sharks are an EU priority after populations decline up to 79% due to unregulated fishing.

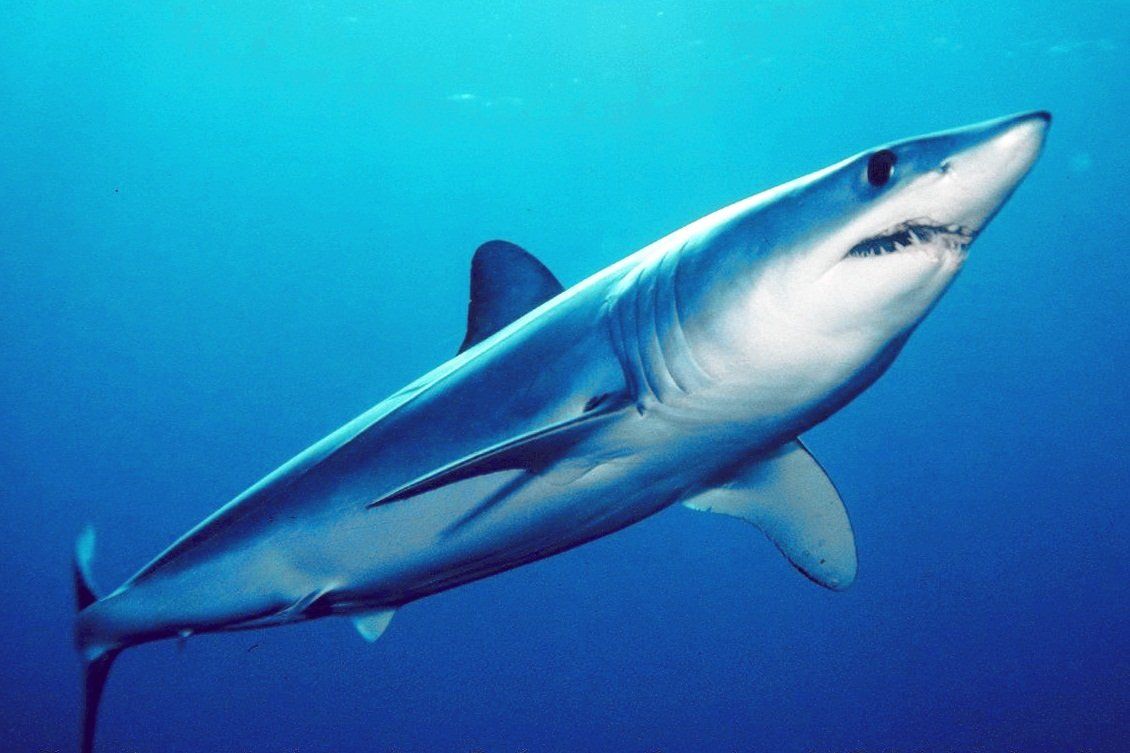

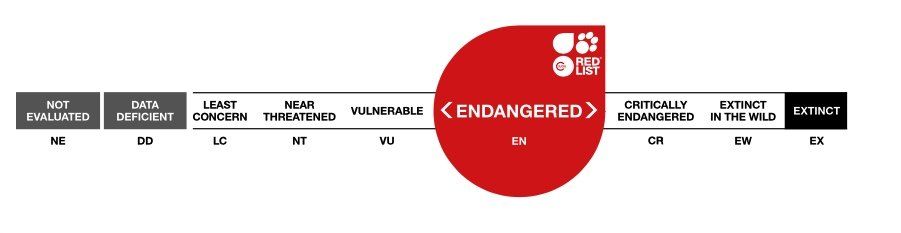

The Shortfin mako may be the world's fastest shark, but it is loosing in the race against extinction. Mako shark populations are declining at an alarming rate and they have now been declared "ENDANGERED" by the IUCN. Overfishing poses a serious threat to not only ocean biodiversity but the entire health of our planet. Shark species around the globe are among the most threatened marine megafauna from excessive and often, unregulated overfishing.

Isurus oxyrinchus by Mark Conlin. Wikicommons

A number of European countries with commercial fisheries for shark species, such as France, Portugal and Spain lack basic catch limits. This can be detrimental for shark populations and is a key driver in global shark declines.

Sharks are particularly vulnerable to fisheries over-exploitation and are slow to recover from depletion due to their long life history strategies. Blue sharks ( Prionace glauca

), mako sharks ( Isurus oxyrinchus

), hammerhead sharks ( Sphyrnidae

) and thresher sharks ( Alopias vulpins

) are among the species most threatened by EU long-liner fishing fleets. These species are considered threatened with extinction as a result of overfishing, with mako's having been updated to "endangered" according to the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red List. The overall estimated median reduction in populations was 46.6%, with the highest probability of 50–79% reduction over three generation lengths (72–75 years), and therefore the species is assessed as Endangered.

Despite the fact that EU waters are overfished, EU fish consumption is still on the rise. Many fishing vessels operate outside the framework of the EU Common Fisheries Policy, but even when vessels are operating under EU law, there are few restrictions on shark fisheries.

A total of 771,000 tons of elasmobranch (shark, skate and ray) catch worldwide was reported in 2005 by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). For the EU, catches up to 100,000 tons, made the European Union the second largest elasmobranch -catching state in the world, after Indonesia and ahead of India! As much as 40% of sharks were caught outside of EU waters, with vessels from Spain, France, Portugal, Lithuania, and Estonia shark fishing in the Pacific Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean and even the Southern Ocean.

Threats to sharks from overfishing has recently been addressed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Species listed as APPENDIX II, it is a requirement that all exported products are legally and sustainably sourced. Mako sharks have taken centre stage at a recent meeting in August 2019, when 28 EU member states voted to list them as Appendix II species, due to their recent population declines.

Over 18 species of mako sharks have been proposed to be protected. Mako's are the world's fastest sharks, and can reach speeds of 130 kph, but they are threatened by commercial fisheries, such as long lining for tuna. Mako sharks are long-lived, slow growing marine top predators and so are particularly vulnerable to overfishing pressures. They are late to become sexually mature, for example, female shortfin mako sharks do not reproduce until they are around 20 years old, after which they produce only around 12 pups, every other year. Although mako sharks are listed as "endangered" on the IUCN Red List, currently there are no quotas for the species.

Several fishing countries with large fishing fleets, including Japan, opposed the proposal to protect mako sharks. Scientists warn that although climate change threatens shark species also, overfishing and the demand for shark fin soup is driving many species to the brink of extinction.

The Pew Trust estimates that 63 - 273 million sharks are killed every year to feed the shark fin trade in Asia. Dried shark fin can sell for up to £1,000/ kilogram, often being made into shark fin soup a Chinese delicacy that symbolises 'good fortune' and whose recipe dates back to the 10th Century Song Dynasty.

Fresh shark fins drying on sidewalk at Hong Kong. Source: wikicommons

In the North Atlantic, mako shark overfishing has reached its limit. The high seas where mako sharks are fished is regulated by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICATT), a regional group composed of 52 fishing nations and the EU. This year, ICATT announced that in order to allow shortfin mako species populations in the North Atalntic to recover over a 25 year period, there is to be a zero catch tolerance.

It is now in the EU's interests to protect shortfin mako sharks, starting with an Atlantic retention ban. The EU should join in the ICATT ban and prohibit Atlantic vessels from keeping mako sharks and choose a more sustainable path. It is vital that we introduce catch limits for some of the Atlantic's most heavy fished species such as shortfin mako and blue shark species, and that we effectively translate into meaningful action to prevent overfishing.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE