MAKO IT HAPPEN!

Sophie A. Maycock | 17th of July 2020.

The short-fin mako shark is a shark of many amazing factoids. It is the worlds fastest shark, clocking in at 60 miles per hour! It jumps higher than any other shark, breaching up to 9 metres out of the water! It has the largest brain to body mass ratio of any shark species, giving them remarkable cognitive skills and incredible sensory capabilities.

But… a mako fact which is not quite so enjoyable, is that they are one of the most threatened shark species in the world.

Shark populations are declining globally due to multiple anthropogenic threats: we overfish them, overfish their prey, degrade their habitats through pollution, run off, dredging and climate change…

Confounding this problem, is a lack of baseline data on shark populations, which can be used to track declines. Today, it is thought that mako shark populations have declined by as much as 79%.

Sharks are particularly vulnerable to extinction, as they have a “K-selected lifehistory strategy”. This means that sharks grow slowly to a large size, become sexually mature relatively late in their lives and live to a ripe old age. They have few offspring, and must invest a lot of resources into reproduction. This compares to what is known as an “R-selected life-history strategy”, we see in animals such as rabbits, mice or locusts. These animals are small, short-lived and, well… “breed like rabbits”, meaning that, even if their population is decimated by human activity, they have a high capacity to bounce back, even from the verge of extinction. Sharks cannot rebound in this way and that is why their protection is so critical.

Mako sharks are struggling especially, due to high mortality of juveniles and females of breeding age in fisheries. Short-fin makos are very commonly fished for their fins and meat, with catches in the North Atlantic currently hitting 3,300 tons annually, which equates to approximately 130,000 individual mako sharks every year.

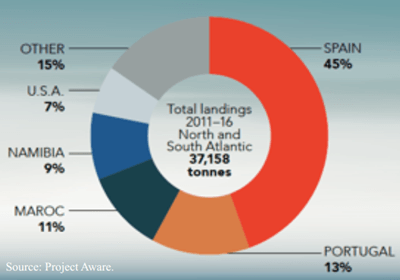

As mako sharks live in the “pelagic” environment (meaning they are commonly found in certain coastal regions, but can also venture offshore into deeper waters), they cross jurisdictional borders and can be fished in “international waters”. Several countries in particular are responsible for landing mako sharks in thousands of tons every year, namely Spain, Portugal and Morocco. The United States, Canada, and Japan also have substantial mako fishing industries.

A stock assessment by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) in 2017, found that the mako shark is overfished in the North Atlantic. The mako has now been listed as endangered by the IUCN (Rigby, 2019) and controls have been enforced, limiting the trade of mako shark products (CITES, 2019). ICCAT recommended that the annual landings of mako sharks must be limited to 500 tons or less in the North Atlantic, but it is predicted that this will mean that the probability of mako shark stocks rebuilding by 2040 is a woeful 35%. In fact, modelling shows that if catches were reduced to zero, there would still only be a 54% probability that the stocks would be restored to a healthy level! What this means, is that if ICCAT advice is adhered to, there is a 65% chance that mako shark populations will not be able to recover over the next 20 years (Sims

et al, 2018).

“Short-fin makos are among the most vulnerable and valuable sharks taken on the high seas, and yet fishery managers have continually put populations at outrageously high risk, allowing serious overfishing year after year. The dire state of North Atlantic makos represents a conservation emergency that calls for immediate retention bans.” - Sonja Fordham, President of Shark Advocates International ICCAT members (48 Parties: from every continent, including the USA, UK and Morocco) have been unable to agree on a quota for the short-fin mako, so, ICCAT compromised with a recommendation that if these sharks are caught alive, they must be released. The thought being that, as 60-80% of sharks are thought to survive after release, optimistically, this would mean that 2,517 tons of mako shark could not be landed annually. But this would still equate to 3-times the upper limit advised by scientists being fished.

No. You did read that right…Your maths is correct… and this does not add up. The action taken by ICCAT will not be effective to protect mako sharks. We need better legislation, we need stricter guidelines and we need them right now.

You can take action!

You can keep yourself up to date on the plight of threatened sharks by following ORCA IRELAND's Shark Research and logging records of sharks to the OBSERVERS APP! Become a citizen scientist today!

Remember, if a lot of us all whisper together, we will become a shout.

Mako it happen!

References:

CITES (2019).

http://checklist.cites.org/#/en/search/

output_layout=alphabetical&level_of_listing=0&show_synonyms=1&show_author=1&show_engli

sh=1&show_spanish=1&show_french=1&scientific_name=Isurus+oxyrinchus&page=1&per_page

=20. Accessed 12.06.2020, 10:25h.

Rigby, C.L., Barreto, R., Carlson, J., Fernando, D., Fordham, S., Francis, M.P., Jabado, R.W., Liu, K.M., Marshall, A., Pacoureau, N., Romanov, E., Sherley, R.B. & Winker, H. (2019). Isurus oxyrinchus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T39341A2903170.

Sims, D.W., Mucientes, G.R., & Queiroz, N. (2018). Shortfin mako sharks threatened by inaction.

Science 359:1342. doi: 10.1126/science.aat0315.

https://www.globalsharkmovement.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/03/Sims-etal_NoMakoRecovery_Science2018.p...