How do Marine Protected Areas Help Marine Mammals?

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) can create a false sense of security to the public without actually fulfilling their conservation role. There are numerous risks with the designation of MPAs including their location,size, tension with other marine users and lack of management practices and monitoring. MPAs have the potential to be effective in protecting migrant marine mammals but currently many of them do not cover the entire range of such species. There is a lack of understanding of marine mammals’ behaviour, distribution and life history which has contributed to uninformed establishments of MPAs which are not protecting the target species they were implemented for. Continued research along with the involvement of local stakeholders, is critical for effective marine spatial planning.

How effective are Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)? Oceans cover 70% of the earth’s surface, yet only 5% of the world’s seas are designated as MPAs. Even the established of MPAs are not always as successful as they may seem in protecting marine biodiversity. While it can be argued that MPAs are a critical tool in combatting marine resource exploitation and habitat degradation, there is a bias towards coastal habitats such as rocky shores in temperate zones and coral reefs in the tropics. As a result, pelagic habitats remain largely unrepresented in MPAs.

Many species of marine mammals are highly mobile, embarking on vast annual migrations to foraging grounds. Migration patterns are not uniform due to the highly dynamic nature of the marine environment, with oceanographic processes driving the distribution of prey. What’s more is that marine mammals’ cross multiple jurisdictional boundaries but MPAs often are fixed to geographical boundaries that do not cover the full range of a certain species. For example, a study carried out in the Bay of Biscay identified important aggregation sites of fin whales Balaenoptera physalus during late summer which were not accounted for by the existing protected areas (García‐Barón et al ., 2018). A transboundary MPA that considers the dynamic marine system would be a more effective approach to protecting this species.

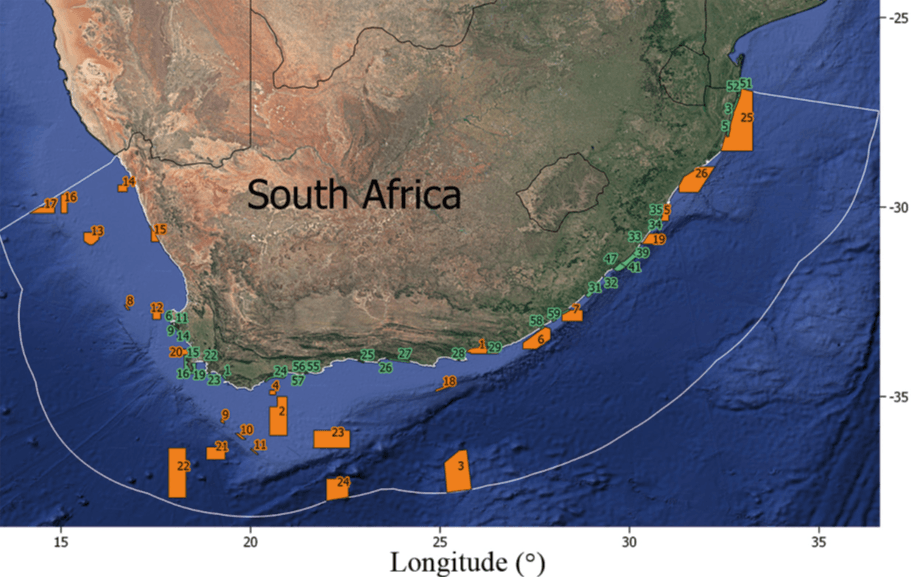

Similarly, on the east coast of South Africa, high occurrences of southern bottlenose whales Hyperoodon planifrons , killer whales Orcinus orca , false killer whales Pseudorca crassidens and Risso’s dolphins Grampus griseus occur , but until recently there were no MPAs protecting this offshore region. Thankfully, three newly approved MPAs have been approved for this location.

MPAs have not been designed for the accelerated changes marine environments are experiencing due to climate and human impacts. It is not enough to define MPAs as stationary single units but instead they should be considered as adaptive networks. Steps towards this approach have occurred. For instance, the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary established a sister sanctuary program in 2006 to protect North Atlantic humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae . This species migrates long distances between the Caribbean and North Atlantic waters. This program aimed to provide sufficient protection for humpback whales at both ends of its range and stands as the first and largest MPA network to protect a transboundary population of humpback whales.

The establishment of MPAs, while in some cases have proven to be effective, can be misleading and provide a false sense of hope to the public. For instance, EU member states are required to follow guidelines set out by the European Union’s Habitat & Species Directive. Under this, member states must designate Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) to species listed under Annex II of this directive. However, marine mammals are underrepresented on this list with only two cetacean species; harbour porpoises Phocoena phocoena and bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus and two pinnipeds; harbour seal Phoca vitulina and grey seal Halichoerus grypus . In addition to this, there are no set protective measures implemented across the network.

What’s more is that EU member states are hesitant to establish SACs, as tension often arises between conservation interests and other marine stakeholders. Local communities adjacent to MPAs often perceive this protective measure as a policing attempt. Communication is lacking between MPA managers and local communities. MPAs are more likely to fail in their conservation goal without the support of local stakeholders. It is critical for effective MPA management that stakeholders are involved in the early planning of MPAs and that locals are educated about the benefits of marine protection and how it can benefit different marine users. Livelihoods rely on resources from our oceans. However, these are depleting rapidly due to overexploitation which is not only unsustainable for marine biodiversity but also for us. How can we continue fishing activities in the sea if there are no fish left? The establishment of effective MPAs will allow marine environments to replenish and restore ecosystem health so that it is beneficial to marine mammals and humans.

In order to make MPAs more effective, they need to be considered on a larger strategic scale with sufficient and informed planning efforts. Marine spatial planning emphasizes that areas should be prioritised based on existing information and data of endangered species including their behaviour, life history, full distribution, abundance and human activities that threaten populations. This approach has been described as a practical way to utilise marine environments while balancing the needs for development and species conservation. There have been significant advances in habitat mapping and surveying of marine mammals in recent years, however information on human impacts remains insufficient. For instance, AIS automatic identification system and VMS vessel monitoring system are useful technologies for mapping shipping traffic but small fishing boats and recreational boats are not always equipped with transmitters required for this technology. What’s more is that anthropogenic pressures on marine mammals are predominantly studied in isolation. How these stressors interact with one another and collectively impact marine mammals is not well understood. Continued research on marine mammals and on human activities is paramount for the establishment of adaptive MPA networks. Additionally, further emphasis needs to be put on long-term monitoring and management of MPAs to ensure that they are protecting species as expected.

References:

Agardy, T., Di Sciara, G.N. and Christie, P. (2011). Mind the gap: addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Marine Policy , 35(2), pp.226-232.

Evans, P.G. (2018). Marine Protected Areas and marine spatial planning for the benefit of marine mammals. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom , 98(5) , pp.973-976.

García‐Barón, I., Authier, M., Caballero, A., Vázquez, J.A., Santos, M.B., Murcia, J.L. and Louzao, M. (2019). Modelling the spatial abundance of a migratory predator: A call for transboundary marine protected areas. Diversity and Distributions , 25(3) , pp.346-360.

Hooker, S.K., Cañadas, A., Hyrenbach, K.D., Corrigan, C., Polovina, J.J. and Reeves, R.R. (2011). Making protected area networks effective for marine top predators. Endangered Species Research , 13(3) , pp.203-218.

Purdon, J., Shabangu, F., Pienaar, M., Somers, M.J. and Findlay, K.P. (2020). South Africa’s newly approved marine protected areas have increased the protected modelled habitat of nine odontocete species. Marine Ecology Progress Series , 633 , pp.1-21.

Wenzel, L., Cid, G., Haskell, B., Clark, A., Quiocho, K., Kiene, W., Causey, B. and Ward, N. (2019). You can choose your relatives: Building marine protected area networks from sister sites. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems , 29 , pp.152-161.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE