HOW CAN WE USE SEABIRD TO MEASURE MARINE LITTER?

Lottie Glover | 10th June 2020.

Plastic may be consumed by marine animals because they may mistake it for food. It then accumulates in the animals’ stomach as it cannot break down and it is difficult to either regurgitate or to pass through the body. This can cause a range of problems including a reduced food in take, digestion problems and reduced breeding success.

The Northern Fulmar is known to commonly ingest plastic and can be found in the North Atlantic and North Pacific. They are particularly susceptible to plastic ingestion because unlike most other seabirds, they do not regurgitate hard prey remains such as bones, or in this case, plastic. Fulmars feed on a variety of food ranging from zooplankton to small fish to discards from commercial fishing. Although their appearance is similar to a gull, it is a member of the Procellariidae family, which also includes petrels and shearwaters. They are part of the order Procellardiiformes, also known as tubenoses, which includes albatrosses.

Fulmars have various morphs ranging from light to dark, and different plumages in-between. The light morph is grey on the upper parts of the body, and white on the underside, with a white head. The dark morphs, also known as ‘Blue Fulmars’, are dark on the upper parts of the body, and pale grey below. This morph is more common in the species northern range. All morphs have a black spot next to their eye.

As a defence against predators, fulmars produce a stomach oil which they can ‘spray’ to mat the feathers of avian predators which may even lead to their death. This oil can also be used as energy-rich food for chicks or for adults during their long foraging journeys.

OSPAR have created a system of EcologicalQuality Objectives (EcoQOs) for the North Sea, providing objectives and indicators to support assessments of ecosystem health and to help inform management actions. Most of the EcoQOs are for specific human activities including litter, fishing, and chemical pollution. Where EcoQOs are not met, it indicates that appropriate measures are needed to regulate the specific human activity, or further investigations may be needed to find out why the EcoQOs are not being met.

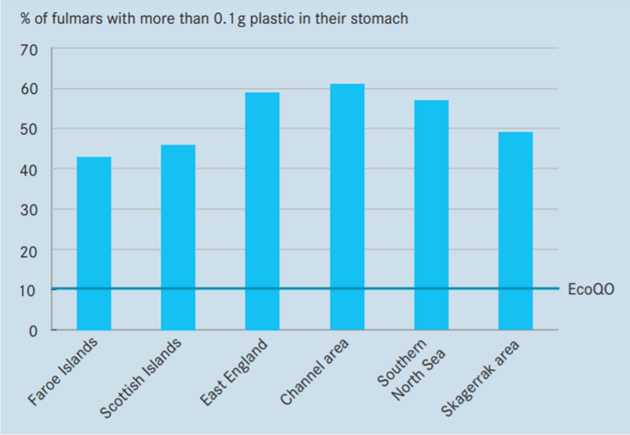

An EcoQO for marine litter was created in the early 2000s, known as the Seabird-Plastic-EcoQO, using the Northern Fulmars in their definition. The preliminary target for acceptable ecological conditions is defined as: “There should be less than 10% of northern fulmars having 0.1 g or more plastic in the stomach in samples of 50-100 beached fulmars from each of 5 different regions of the North Sea over a period of at least 5 years”. The EcoQO was originally used in a pilot study in theNetherlands, investigating the use of beached fulmars as an indicator of the effectiveness of Dutch shipping and harbour policies regarding waste disposal at sea. This is now used as an indicator for Good Environmental Status in EuropeanMarine Strategy Framework Directive.

A study by van Franeker

et al ., (2011)looked at the levels of plastic ingestion in beached fulmars from 1980s-2011from various locations in the North Sea, and the Faroe Islands. Once data such as breeding status, sex, age and probably cause of death were assessed, each bird was dissected to investigate the stomach contents to see if any plastic was present. Any plastic found was split into industrial and user plastics, then the number of items and their combined mass were measured.

The study found that a percentage of beached fulmars that had ingested plastic was 91% in the 1980s, 98% in 2000 and95% in the period of 2003-2007. The average mass of plastic ingested was 0.34gin the 1980s, 0.64g in 2000 and 0.28g in 2003-2007. Between 2003 and 2007, an average of 58% of fulmars examined exceed the target described above for thisEcoQO in the North Sea. This suggests there needs to be further investigations and improved measures/policies to prevent marine litter in the North Sea.

Between 2013 and 2017, 46% of fulmars studied contained more than 0.1g of plastic, with an average mass of 0.26g of plastic found in each bird (van Franeker and Kuhn, 2018). However, it is still not possible to pinpoint why these changes have occurred. It is predicted that the EcoQO target of 10% of fulmars containing more than 0.1g of plastic may beach by around 2060.

The EcoQO for marine litter has been used in other studies, altered for the specific species and their weight. For example, if the EcoQO of the fulmars was adapted to the Flesh-footedShearwater, no more than 10% of the bird studied should contain 0.12g of plastic. Lavers et al., (2014) found that over 60% of Flesh-footed Shearwater fledglings exceeded the target that was adapted to this species, with 16% of fledglings exceeding the target after a single feeding.

Lavers, J. L., Bond, A. L. and Hutton. I.

2014. Plastic ingestion by Flesh-footed Shearwater fledglings ( Puffinus

carneipes

): Implications for fledgling body condition and the accumulation

of plastic-derived chemicals. Environmental Pollution.

187

, pp.

124-129.

van Franeker, J. A., Blaize, C., Danielsen,

J., Fairclough, K., Gollan, J., Guse, N., Hansen, P. L., Heubeck, M., Jensen,

J. K., Le Guillou, G., Olsen, B., Olsen, K. O., Pedersen, J., Stienen, E. W. M.

and Turner, D. M. 2011. Monitoring plastic ingestion by the northern fulmar

Fulmarus glacialis in the North Sea. Environmental Pollution

. 159

,

pp. 2609-2615.

van Franeker J. A. and Kuhn, S. 2018.

Fulmar Litter EcoQO monitoring in the Netherlands- Update 2017. Wageningen

Marine Research Report C060/18 & RWS Centrale Informatievoorziening BM

18.20.