Halloween Special: Evolution's ultimate predators - Top 10 Most Terrifying Extinct Sea Beasts.

Once upon a time, we feared the oceans and its nightmarish sea beasts which haunted the periphery of an unknown world, a perilous threat to daring sailors! Were our fears un-founded?, or did they stem from ancestral memory of a long forgotten world?

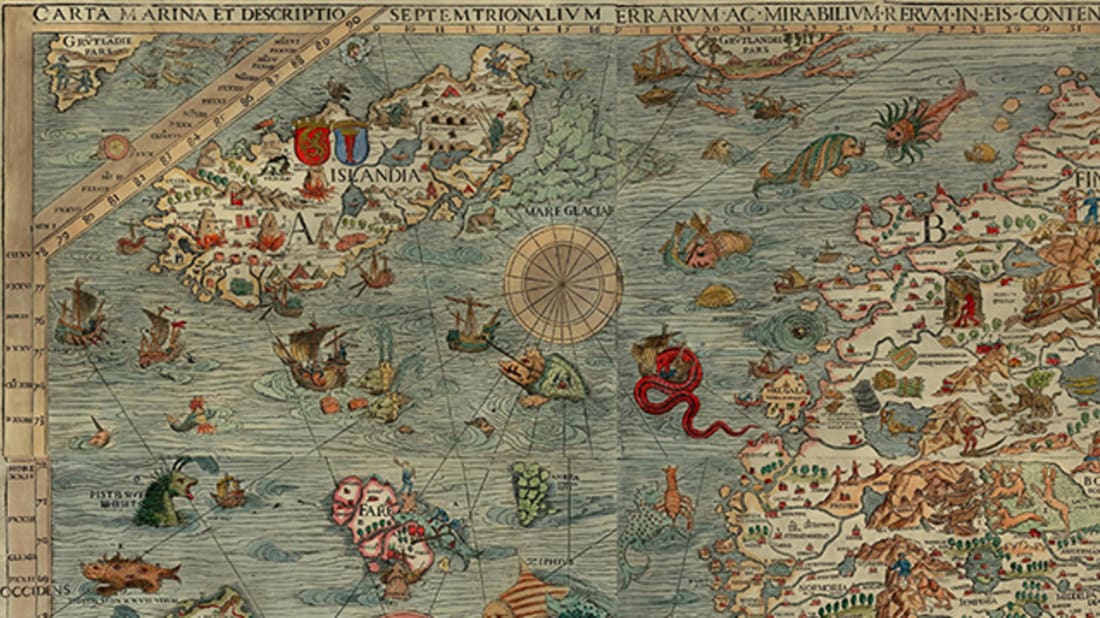

OLAUS MAGNUS (1539) VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS // PUBLIC DOMAIN

Ancient cartographers who created centuries old maps, didn't just create geographical maps, they were also supernatural illustrations. Medieval and Renaissance mapmakers sketched spirited drawings of mythical sea monsters off the coasts and around far reaching islands. What was it that made these illustrated seas so terrifying?

Among historians, the consensus is it was part decoration, part a declaration of ignorance. During the Medieval and Renaissance people didn't know what was out there, so influences from the bible and folklore filled the gaps in knowledge of un-chartered waters. Perhaps however there were tapping into some kind of ancestral memory - If we go back 40-50 million years before present (ybp), you could meet some horrifying marine top predators at sea.

It is well known that along the path of evolution, humans slithered from the oceans, but it is less common knowledge that some early mammals that left the oceans weren't too impressed with terrestrial living. These creatures emerged, took one look, said "MEH" and headed back into the depths of the "big ocean blue". This turnaround may have taken several million years of adaptation, however they became the granny and grandads of the cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoise). Some ancestors of modern day sharks, evolved their own uniquely spooky set of adaptations that allowed them to be some of the most ferocious predators to have ever existed, and will make you grateful you were born in 21st Century! Either way it is not hard to see where these medieval illustrations of sea beasts on navigational maps abounds from.

To celebrate Halloween 2019 we are counting down the Top 10 Most Terrifying Extinct Sea Beasts!

1. Pakicetus inaches

The only sounds along the quiet shoreline are the waves lapping between a few small rocks. Wait, are those rocks? Did they just blink? Suddenly a giant dog-rat with a snout like a crocodile rises up from the water, a fish clenched in its massive jaws! This, believe it or not is an ancient whale Pakicetus

inachus.

The fossils of this ancient whale species was first found in the 1980's by a team of palaeontologists who were examining rock formations in Northern Pakistan. Unlike modern whales, the scientists noted that it had a rather small Brian cavity relative to the size of the skull and it also had a tympanic bone which limited underwater hearing. These two features allowed the researchers to age the fossil to at least 50 million years.

2. Liopleurodon

A prehistoric marine reptile group known as Plesiosaurs, existed around the same time of the dinosaurs which often leads to confusion between the two groups. As you can imagine, Jurassic oceans were a pretty scary place to be, but one plesiosaur you would have needed to watch out for was the liopleurodon. This carnivorous sea monster weighed over 1500 kg and reached up to 10 meters in length. One terrifying adaptation that allowed liopleurodon to be such a successful predator was it's characteristically enormous jaws, equipped with several rows of razor-sharp teeth. Watch it in action....if you dare! https://youtu.be/3D4AA_l6c3w

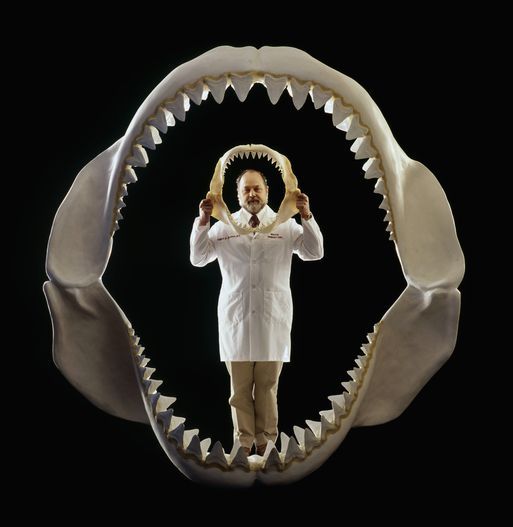

3. Megalodon

Actual megalodon tooth compared to teeth from a great white shark. Image Source: Wikipedia

The Megalodon is perhaps one of the most well known enormous extinct shark species thanks to it being the largest shark to have ever existed. In appearance, it is similar to a great white shark, however, in comparison to a great white which weighs 3,000 kg and can reach over 6 meters in length, the megalodon weighed anywhere from 50 to 100 metric tons and could reach lengths of 20 meters. Megalodon went extinct 2.6 millions years ago, meaning that this shark likely fed on animals which are still around today such as giant sea turtles, porpoises and the even great whales. Check this video out for more info: https://youtu.be/Spo8vkrJFRo

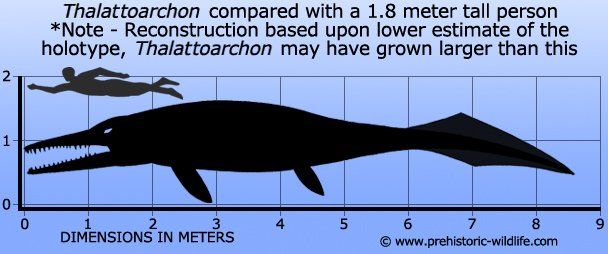

4. Thallatoarchon

A new species of sea monster - a bus sized ancient marine reptile which was the only species that evolved to take prey of it's own size, was only recently discovered in the U.S. The fossil of thallatoarchon was discovered in Nevada in 2010. Excavations at the site began in 1998, however it wasn't until palaeontologist, Nadia Fröbisch of Berlin's Museum of Natural History , returned to finish digging the site that they discovered the massive skill, jaws and teeth of this extinct marine reptile. This beast was beast was an early ichthyosaur, part of a group of reptiles that prowled the world's seas during the dinosaur era. Its full scientific name; Thalattoarchon saurophagis— translates to "lizard-eating sovereign of the sea"—it was at least 8.6 meters long and lived about 244 million years ago during the Triassic period. Thalattoarchon 's modern-day equivellants would be orcas and great white sharks , both of which will take on similar-size prey.

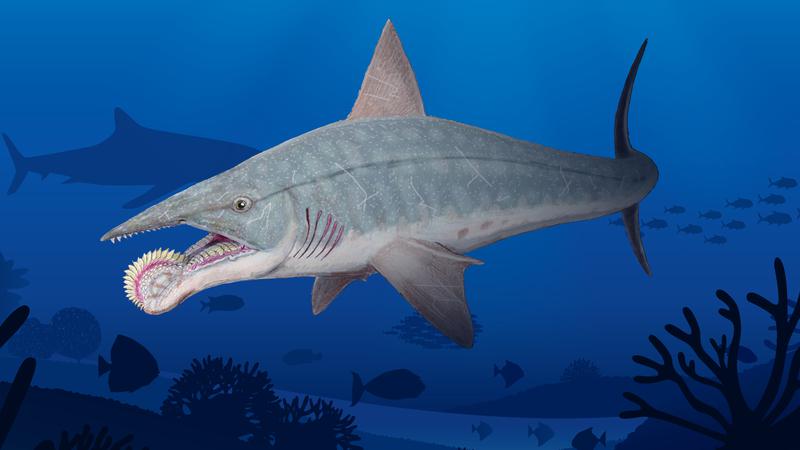

5. Helicoprion

Helicoprion shark reconstruction (public signage, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

The Helicoprion would have been downright freaky shark to encounter 250 million years ago, during the early Permian and early Triassic periods as it practically had a buzzsaw attached to its lower jaw! Some paleontologists have interpreted the tooth whorl of this fossil edestoid shark to be part of a coiled lower jaw that may have been whipped outward and back to capture fish prey. Although intriguing, this type of reconstruction (seen above) is likely incorrect. Instead, the tooth whorl was likely internal. This interpretation is based on well-preserved specimens with soft-part preservation from concretions in the Permian-aged Phosphoria Formation of southeastern Idaho, USA.

You may know that modern sharks have multiple rows of teeth , with rows in the back constantly pushing forward to replace the ones that have been lost in the front. Helicoprion was similar in this regard. In fact, that might have been one of the primary features of the tooth wheel — the ones at the very inside of the spiral of wheel would have slowly been pushing forward to replace the ones on the outside. So maybe the buzzsaw really did "buzz," just very, very, very slowly. Still, this is one monster we're glad we didn't share the planet with.

6. Pentecopterus decorahensis

Imagine a sea scorpion with a paddle-shaped body meant for swimming. Now imagine more than 1.5 meters in length. The Pentecopterus decorahensis, just discovered in 2015, swam around what is now roughly 460 million years ago in Iowa, USA. The discovery of this new species was published in an open access journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. It is now the oldest known species of eurypterid - ancient sea scorpions that are related to modern day spiders and ticks.

This is not a creature you would have wanted to encounter if in the sea for a swim, given its size and collection of forelimbs designed for capturing prey.

7. Anomalocaris

It's a shrimp! It's a squid! No, it's a hideous 6-ft. long carnivorous anomalocaridid, a family of animals thought to be closely related to ancestral arthropods, and it had tentacles with teeth on them. Their species name literally translates to "abnormal shrimp."

Long before killer whales and polar bears, sharks and tyrannosaurs, the world’s top predator was probably a bizarre animal called Anomalocaris. It was extant during Cambrian period, over half a billion years ago, when life was confined to the seas and animals took on bizarre shapes that haven’t been seen since.

Palaeontologists believe that Anomalocaris

ruled this primordial world as a top predator. Reaching up to a metre in length, it was the largest hunter of its time and chased after prey with undulating flaps on its sides and a large fan-shaped tail. It tracked its prey with excellent vision from its large stalked eyes. Using large spiked arms, it captured its prey to bring them to its square, tooth-lined mouth.

Here's a terrifying video

of what they would have looked like in action.

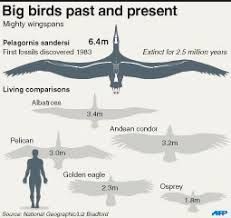

8. Pelagornis sandersi

The biggest bird ever to grace the skies, with a wingspan of up to 6.4 metres, Pelagornis sandersi

was nearly twice the width of a wandering albatross

, the living bird with the greatest wingspan, at 3.5 metres.

P. sandersi lived around 25 million years ago. The first fossils found were a skull plus some wing and leg bones, discovered in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1983. Now scientists from North Carolina State University in Raleigh who have formally described it, and worked out its size and how it flew, estimates its wingspan may have been as much as 7.4 metres.

The bird’s longer wings would have reduced the size of wingtip vortices , which otherwise produce drag. Therefore, P. sandersi was probably a consummate glider that soared for hundreds of kilometres over the open ocean with barely a flap of its wings, swooping down now and then to pluck fish or squid from the water.

Not great for anyone who has been traumatised by Stephen King's "Birds". Check out this interesting video about how the biggest bird to have ever lived stayed airborne. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iZkVBCgmZ_E.

9.Basilosaurus

About 37 million years ago, the ancient whale Basilosaurus isis ruled the seas as an apex predator, according to new research. (Credit: Asmoth/Wikimedia Commons)

The archaic whale Basilosaurus was extant in the late Eocene epoch, from about 38–34 million ybp,. It had a large range and broad marine distribution at a time when few modern whales existed. Two species have been described, Basilosaurus isis and its slightly younger sister taxon B. cetoides.

One thing paleontologists were puzzled over, was the animal’s feeding behaviour. While its sheer size and toothy grin might suggest apex predator, some researchers believe it was more likely a scavenger in the shallow late Eocene seas it called home.

A recent study published in PLoSONE show from stomach contents that it fed on smaller whales (juvenile Dorudon atrox ) and large fishes ( Pycnodus mokattamensis ). Evidence of whales preying on other whales is uncommon, both in the fossil record and among living species. But it does occur. Read our blog about it here.

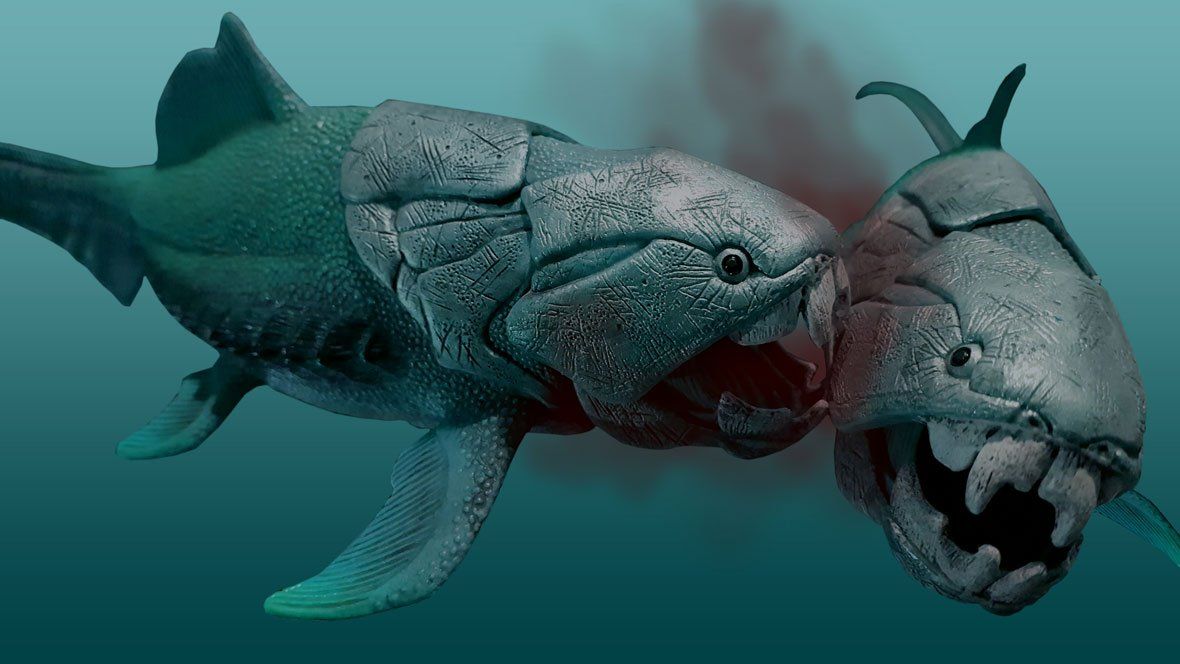

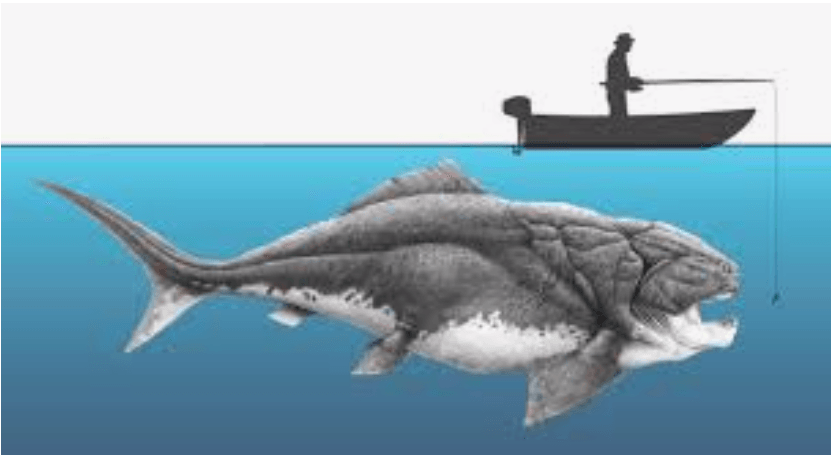

10. Dunkleosteus

This prehistoric fish lived 400 million years ago during the Devonian period, but its bite has stood the test of time. Scientists believe the Dunkleosteus had the strongest bite of any fish

ever discovered - one that could be compared to the bite of a Tyrannosaurus rex! Scientists have crunched the numbers and determined that, just at the tip of its fang, this fish’s bite could measure at 8,000 pounds per square inch. They were absolute apex predators, preying on sharks and basically anything it could catch which given its powerful body was pretty much everything!.

New fossil research presented at the Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology shows that, as full-grown adults, these top predators had jaws strong enough to take down just about anything in their habitat – even each other.

The Cleveland Museum's most famous skull of Dunkleosteus , nicknamed "Dunk".

Dunkleosteus

had no true teeth; instead, the skull's bony plates extended into sharpened "fangs" protruding from the mouth. These fangs scraped together, continuously sharpening each other as the fish opened and closed its jaws.

As the fish grew, the jaws gradually lengthened, while the fangs up front grew stronger. So, the jaws of an adult closed more slowly, but with a lot more power. Thus, the younger fish ate smaller, softer prey, while the adults were capable of punching through even other heavily armoured arthrodires.

Dunkleosteus was also 10 meters long from tooth to tail and covered in thick armor-like plating, making it one of the ocean’s first giant predators.

IF YOU LIKE OUR WORK AND WANT TO SEE READ MORE INTERESTING ORIGINAL ARTICLES ON TOPICS IN MARINE BIOLOGY PLEASE SUPPORT US BY VISITING OUR WEBSITE AND MAKING A DONATION TODAY!

- © Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and

www.orcireland.ie

, est. 2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland and

www.orcireland.ie

with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE