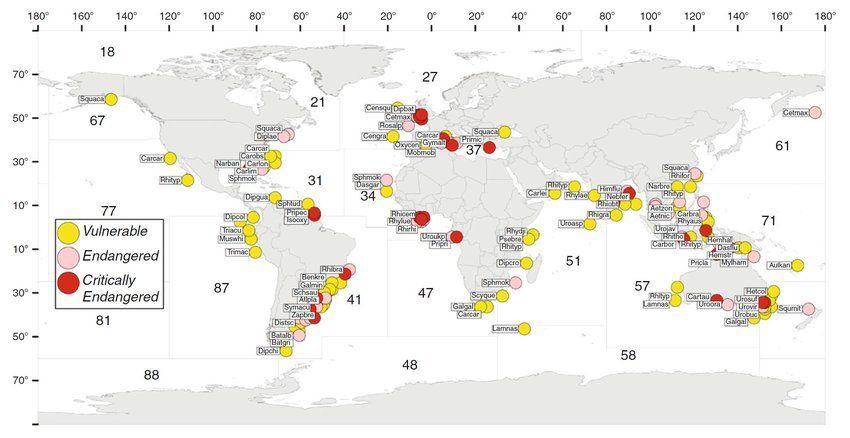

Global threats to shark populations.

An essential and complex balance exists between marine ecosystems and their inhabitants. Elasmobranchs, which include sharks, skates and rays, are estimated to have a quarter of their species threatened with extinction and are one of the most threatened groups of vertebrates (Hobbs et al. 2019).

As an apex predator, sharks are particularly important to functioning marine ecosystems as they directly influence the population size of prey communities, prey behaviour and space utilization (Heithaus et al . 2008). Research has found sharks possess larger brains than other ectothermic vertebrates (Northcutt 1977), they have slow growth rates, late sexual maturation, long gestation periods and low fecundity (birth rate). As a result, these life characteristics make them vulnerable to overexploitation and could be the dominant driver behind population declines (Hobbs et al. 2019, Sims 2015, Cailliet and Goodman, 2004). Other key factors which pose serious threats to elasmobranchs are mislabelling of shark meat by final sellers, persecution and climate change.

Fisheries and Overexploitation of sharks

The consumption of shark meat has been part of the human diet for centuries from the eastern to western world and in both developed and developing countries. However, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization only 15% of shark catches are identified and reported at the species level while many sharks are simply not recorded or identified in fisheries statistics, ( Dulvy et al. 2008 ). In developing countries where communities aren’t as financially stable as developed countries, it can be an important source of protein for coastal communities, particularly those supported by small-scale artisanal fishing. Shark fisheries and shark fin trade has seen a considerable increase worldwide since the 1980’s. This increase demand for shark meat and fins has raised concern about shark extinction risks and population declines. This has led to 12 shark species being listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES) (Hobbs et al . 2019). In some developed countries where there are cultural barriers associated with the consumption of shark meat, these barriers are breached by re-labelling of shark meat (Bornatowski et al. 2014, Hobbs et al. 2019). Studies in the UK have found that Shark can be purchased battered and deep fried in fish and chip shops under the alias of “flake” or “rock salmon”. Advanced methods of DNA analysis known as DNA barcoding can be applied to these “mysterious” fish to identify which species of sharks are being consumed. DNA barcoding involves sequencing a partial region of the cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene, and this allows for species identification (Hobbs et al ., 2019).

Shark bycatch

Bycatch refers to any species caught accidentally while fishing for other commercially important species. According to the FAO , approximately half of the sharks that are caught and sold were caught as bycatch in the high seas longline fisheries. Estimates suggest tens of millions of sharks are caught as bycatch every year.

There is a high demand for shark fins on the Asian food market, driving down the chance of bycaught sharks survival, and up the likelihood they will be finned first, thus blurring the line between accidental bycatch and targeted fisheries. Some of the most notorious fishing gear for bycatch is longlines, trawls and gillnets.

Longline fishing uses thousands of baited hooks hanging from a single line, often miles long. Swordfish, tuna, mackerel and sharks are commonly targeted by these fisheries. Longlines catch a large amount of bycatch because the baited hooks provide an easy meal for any indiscriminate predator, including sharks. They are often set in the water for extended periods of time, and by the time they are removed from the water, the hooked sharks are often dead.

A trawl is a large net that is pulled through the water column or along the seabed. This fishing gear is typically used to catch fish or shrimp. Catching unwanted species, such as sharks, is a problem for trawlers because it is a non-target form of fishing. Trawling can occur with one boat pulling a net or cooperatively by two boats, each pulling an end of a much larger trawl net, known as pair trawling.

Gillnets are long walls of netting hung in the water to trap and hold fish. A fish swims into the invisible netting and as it swims in reverse to try to dislodge, its gills become caught in the net. Sharks, like other fish, often become entangled in the netting even if they are not the targeted species. If the trapped sharks are still alive when the net is retrieved, they are often injured and stressed.

Persecution of sharks

Despite the low numbers of shark attacks that occur worldwide each year, shark encounters attract a high level of public and media attention which can have serious and fatal consequences for both parties (West 2010). To remedy shark attacks operations such as shark control programs are put in place with the aim of reducing contact between both species by fixing a physical barrier in water bodies and areas frequented by the general public. Although these barriers are effective at protecting humans from encountering sharks they are detrimental to other marine life frequenting the areas and often lead to increased mortality of small elasmobranchs that are not dangerous, in addition to fish, marine turtles, whales, dolphins, and other important marine life (Dudley & Cliff 2003; 2010 ). Data analysed from the Australian Shark Attack File has shown that the rise In Australian shark attacks from 6.5 incidents per year during 1990-2000 to 15 incidents per year over the past decade corresponds with an increasing human population resulting in more people visiting beaches and participating in water-based fitness and recreational activities. There is no evidence in increasing shark numbers that would influence the rise of attacks in Australian waters. However, over the past two decades the increase in number of shark attacks is consistent with international statistics of shark attacks increasing annually as a result of greater numbers of people in the water (West 2010).

Climate Change

Globally climate change is regarded as one of the principal threats to biodiversity. In aquatic habitats species of shark that are associated with freshwater/estuarine and reef could be most vulnerable to climate changes (Field et al . 2009). Climate change will impact greatly on shark species who have restricted ranges and species that depend on special nearshore habitats such as mangroves or coral reefs. The rise in sea temperatures as a result of climate change can cause a shift in the distribution of shark species either towards north or south poles or to deeper waters and an enhancement of bioaccumulation of pollutants (metals, DDTs, PCBs) (Kibria et al . 2017).

By removing top predators (sharks), from an ecosystem the problems stemming from this loss are devastating and complex and as a result, negative implications have been reported for entire marine ecosystems (Baum & Myers 2004, Myers et al. 2007). An increase in the population of their main prey (meso-consumers which are predatory or herbivorous species) and a collapse in primary producers at lower trophic levels (resource species) is a direct result from removing an apex predator (Heithaus et al. 2008). To protect and conserve our sharks, more research is needed to help estimate population trends. The development and promotion of citizen science programmes for elasmobranch and shark research can have major benefits and contribution to scientific research worldwide. In Queensland Australia, Grey Nurse Shark Watch (GNS Watch) was established in 2011. It is a citizen science research and monitoring program that aims to use the data obtained citizen scientists to improve the conservation management of the GNS in Australia and to help the Critically Endangered east coast population to recover. The research team and project officers use this data to re-sight and identify individual sharks, study their movement patterns, site fidelities and estimate its population. It also allows monitors foul hooking of individual sharks and promotes the removal of foul hooks ( www.1).

In Ireland, Inland Fisheries Ireland (IFI) promotes citizen science by way of marine sport fish tagging programme. This programme was established in 1970 and it is one of the longest tagging programmes of its kind in the world. Tags are provided to sport fishermen for the deployment on elasmobranchs caught while sport angling. The biometrics of the animal are also recorded and give a good indication of the population of elasmobranchs and sharks occurring in Irish waters. Recapture data is recorded and verified before publishing ( www.2).

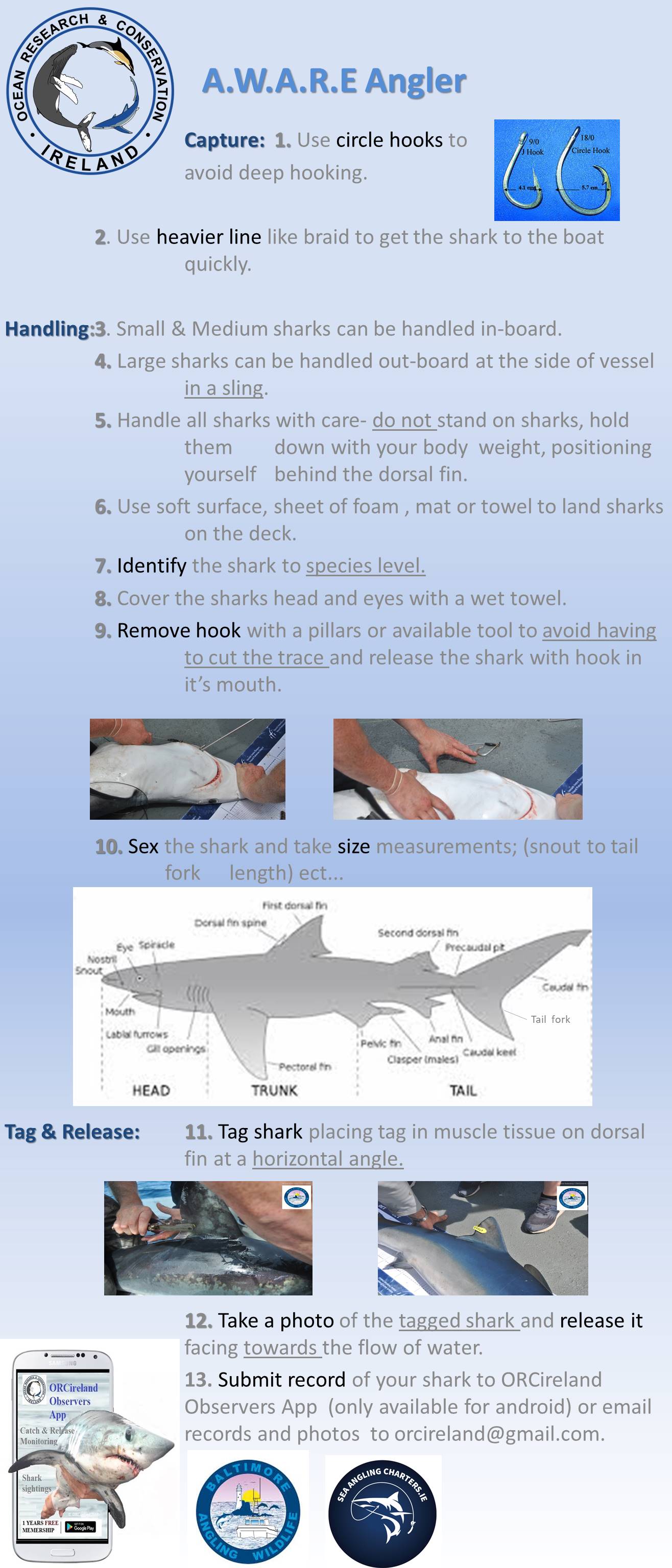

Anglers all around Ireland are also invited to contribute to citizen science by submitting records of sharks species they catch and release from land or boat, through the "O.R.C.Ireland Observers" App available to download free on our website homepage www.orcireland.ie and are encouraged to follow our best practices below;

Recent studies have proven that there is a growing recognition of the sensory nervous system in fish can respond to certain harmful or potentially harmful stimuli. On the contrary to most people’s beliefs, fish and sharks have some capacity to experience pain and fear. By introducing angling welfare standards and analysing the data from existing catch and release research new strategies are developed and could be adopted by anglers to minimize harmful effects on the catch through changes in either gear (e.g., type of hook, line, bait, or net) or angling practices (e.g., duration of fight and air exposure, fishing during extreme environmental conditions, fishing during the reproductive period). Although consideration of fish/shark welfare is somewhat abstract to most fisheries managers and anglers, ultimately it benefits the individual fish, while simultaneously benefiting the population and fishery (Cooke & Sneedon 2007). As key predators, the depletion of sharks has risks for the health of entire ocean ecosystems.

References

·Baum, J. K., Myers, R. A., 2004, Shifting baselines and the decline of pelagic sharks in the Gulf of Mexico, Ecology Letters , 7 (2).

· Bornatowski , H., RennóBraga , R., SimõesVitule, J. R., 2014, Threats to sharks in a developing country: The need for effective simple conservation measures, Natureza & Conservação , 12 (1 ), 11-18.

·Cooke, S. J, Sneedon, L. U., 2007, Animal Welfare Perspectives on Recreational Angling, Applied Animal Behaviour Science , 104 (3), 176-198.

·Dulvy, N. K., Baum, J. K., Clarke, S., Compagno, L. J. V., Corte’Se , E., Domingof, A. S., Fordham,S., Fowler, S., Francis, M. P., Gibson, C., Marti’Nez, J., Musick, J. A., Soldoi, A., Steven, J. D., Valenti, S., 2008, You can swim but you can’t hide: the global status and conservation of oceanic pelagic sharks and rays, Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst , 18 : 459–482.

·Field, I. C., Meekan, M. G., Buckworth, R. C., Bradshaw, C. J. A., 2009, Susceptibility of Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras to Global Extinction, Advances in Marine Biology , 56 , 275-363.

·Heithaus, M. R., Freid, A., Wirsing, A. J., Worm, B., 2008, Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines, Trends Ecol Evol , 23 (10):537.

·Hobbs, C. A. D., Potts, R. W. A., Walsh, M. B., Usher, J., Griffiths, A. M., 2019, Using DNA Barcoding to Investigate Patterns of Species Utilisation in UK Shark Products Reveals Threatened Species on Sale, Scientific Reports, 9 (1028).

·Kibria, G., Yousuf Haroon, A. K., Nugegoda, D., 2017, Climate change and its effects on global shark fisheries, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15363.8144

·Myers, R. A., Baum, J.K., Shepherd, T. D., Powers, S. P., Peterson, C. H., 2007, Cascading effects of the loss of apex predatory sharks from a coastal ocean, Science , 315 (5820):1846-50.

·Northcutt, R. G., 1977, Elasmobranch Central Nervous System Organization and Its Possible Evolutionary Significance, AMER. ZOOL ., 17 :411-429.

·Sims, D. W., 2015, Introduction to the symposium the biology, ecology and conservation of elasmobranchs: recent advances and new frontiers, Journal of Fish Biology , 87 , 1265-1270.

·West, J. G., 2010, Changing patterns of shark attacks in Australian waters, Marine and Freshwater Research 62 (6) 744-754.

Websites

·www. 1 https://www.reefcheckaustralia.org/grey_nurse_shark_watch

·www.2 https://www.fisheriesireland.ie/Tagging/marine-sport-fish-tagging-programme.html

Images

· https://www.google.com/search?q=school+of+hammerheads&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=... :

· https://www.google.com/search?q=jaws&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj2tuSYvbvg... :

· https://www.google.com/search?tbm=isch&sa=1&ei=wIFlXOWwLviE1fAPpOGZuA8&q=shark+nets&... :

SHARE THIS ARTICLE