Endangered Sharks on the Menu in the U.K.

Sophie A. Maycock | 23rd July 2020.

The “elasmobranchs” (sharks, skates, and rays) are amongst the most threatened group of vertebrates globally, with declines of 70% on average across all species. Habitat loss and degradation, climate change, and mortality from beach nets are all implicated in the depletion of sharks, but over-fishing is the main driver of population declines world-wide. Sharks are extracted for their oils, jaws, and teeth, but predominantly for their fins and meat, which are sold for human consumption.

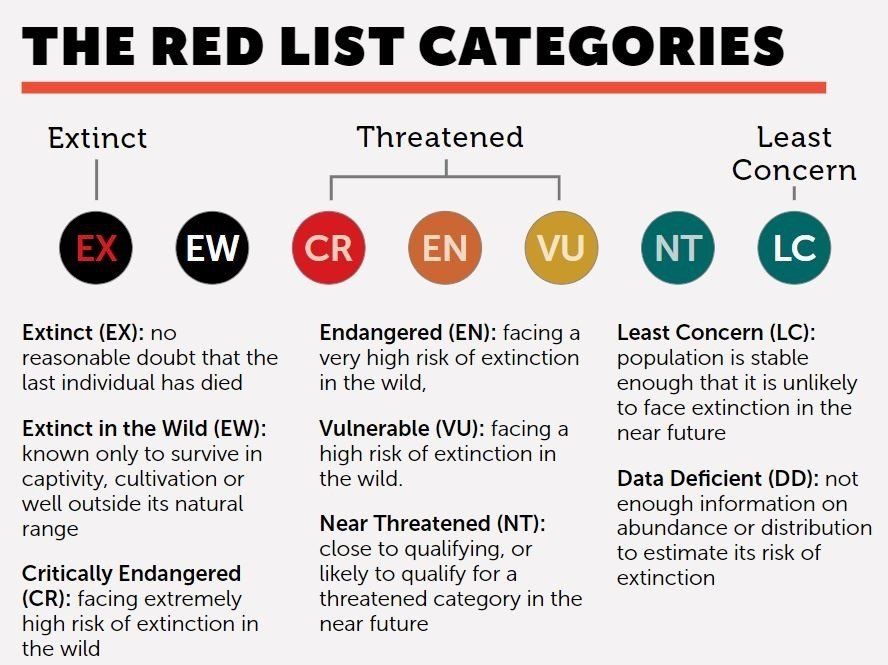

In order to assess the health of wild animal populations, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) categorises how threatened each species is on its ‘Red List’; from ‘least concern’ to ‘extinct’. When species are considered threatened, they may be subjected to legislation for their protection. For instance, in response to concerns over declines, several species of sharks have been listed on AppendixII of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES), which limits and monitors the international trade of endangered species. CITES seeks to ensure that trade will not be detrimental to populations on a global scale. On a more localised scale, in the EuropeanUnion, fisheries are also regulated by Total Allowable Catches (TAC) which can limit landings. For instance, the spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias ) EU catch limits have been reduced by TACs, in order to attempt to reverse their population declines. This shark was once one of the most abundant shark species worldwide, but is now estimated to have declined by as much as 95% from their natural population size. The spiny dogfish is categorised by the IUCN Red List as ‘vulnerable’ globally and the Northeast Atlantic sub-population is specifically listed as ‘critically endangered’.

In the EU there are also strict laws regarding food labelling; requiring that commercial and scientific names are displayed on fish packaging, so that even filleted fish can be identified accurately. This is critical to ensure that consumers know what fish they are buying; meaning people can make informed choices regarding allergens, ethics and toxin contents (such as mercury in certain species).

But are the measures working to ensure that endangered species do not turn up on the menu in the UK?

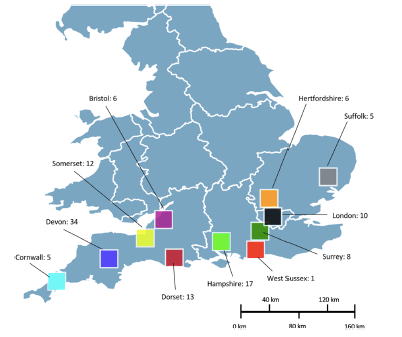

A recent study used DNA barcoding to identify exactly what species were on sale for human consumption at fishmongers and in takeaway restaurants. The researchers took DNA samples from 117 shark meat products and 36 shark fins which were on sale in 90 different retailers across the south of England.They compared a specific region of the genetic code (called a "barcode”) against a database of known species, which allows them to identify the exact species, even if the fish was filleted, frozen or processed to the point that it was not recognisable (Hobbs et al, 2019).

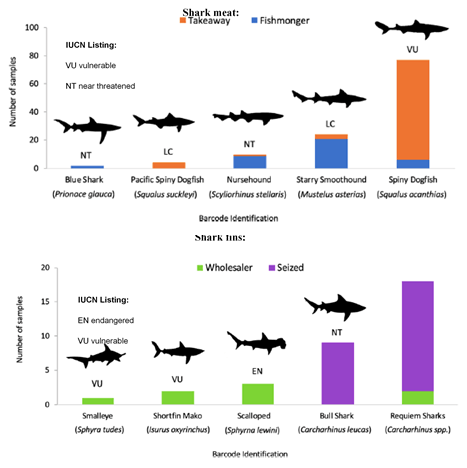

The study found that five shark species were on sale in the form of meat or fillets in takeaways and fishmongers around the UK: the spiny dogfish, the starry smooth-hound (Mustelus asterias ), the nurse-hound (Scyliorhinus stellaris), the Pacific spiny dogfish (Squalus suckleyi) and the blue shark (Prionace glauca).These species are native to British and EU waters. Alarmingly, both the nursehound and the blue shark are classified as ‘near threatened’ by the IUCN. Whats more, the ‘vulnerable’ spiny dogfish made up the vast majority of samples which were analysed (Hobbs

et al,

2019).

The researchers also found four specific different shark species for sale in the form of fins: the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas ), the scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrnalewini),the small eye hammerhead (Sphyrna tudes ) and the short-fin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus . The remaining fins were lumped into with the ‘

Carcharhinus species’, as they could not be identified to a species level.Both the small eye hammerhead and the short-fin mako are classified as ‘vulnerable’ by the IUCN and, the scalloped hammerhead is listed as ‘endangered’ and included on CITES Appendix II to limit its trade. All of these species of sharks are not found in waters of the UK and must have been imported into the country from international fisheries (Hobbs et al,2019).

This study also found that, whilst packaging was not technically incorrect, the details of what species was actually being sold were very vague. Many fresh and frozen meat products only used an ‘umbrella’ term to refer to a certain species, grouping many species into one category. Shark meat was commonly labelled as “Rock”, “Huss” and “Rock Salmon”, which is extremely misleading and does not conform to EU legislation for seafood labelling. The researchers stated this practice makes it very challenging for consumers to make informed decisions and removes the consumers’ right to avoid consuming endangered species (Hobbs

et al, 2019).

The researchers concluded that several species of threatened sharks are on sale in the UK and poor labelling is denying consumers the right to choose not to purchase these products. We often point the finger of blame towards Asian countries when discussing global shark declines, as these countries extract and/or import an enormous number of sharks annually for shark fin soup. However, this study shows that the UK and Europe also plays a role! Not only do UK fisheries extract sharks in unsustainable numbers in our own waters, but we also support international fisheries extracting sharks, by importing their products into the country (Hobbs et al,

2019).

If you want to avoid purchasing meat from endangered species of sharks in the UK you can:

• Only buy seafood with a logo on the packaging which shows it was sourced from a sustainable fishery

• Avoid buying any fish labelled as“Rock”, “Huss” or “Rock Salmon”,as this may be an umbrella term which actually refers to shark meat

References:

Hobbs

CAD, Potts RWA, Walsh MB, Usher J & Griffiths AM ( 2019

). Using DNA Barcoding to Investigate Patterns

of Species Utilisation in UK Shark Products Reveals Threatened Species on

Sale. Scientific Reports

, 9:1028. Access online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-38270-3

.

IUCN

( 2020

). Access online: www.iucnredlist.org