Climate Change: The Final Blow For Whales?

A recent study forecasts a grim and uncertain future for the population of baleen whales in the Southern Ocean. Researchers have developed a coupled ecosystem-climate model to investigate the impact of historical commercial whaling combined with climate change on the recovery of these whale populations. The results are extremely concerning, predicting that climate change could lead to the local extinction of different whale species as early as 2100.

Before the banning of commercial whaling by the International Whaling Commission in 1986, baleen whale species were subject to intensive overexploitation during the 19th and 20th century, which almost led to their extinction. It seemed the protective measures were helping their population to recover, but with climate change, they are now facing the next worrisome peril. Baleen whales rely on stable environmental conditions and food resource availability in polar waters (such as krill or copepods) for their survival. Their slow growth rates and dependence on lower trophic prey makes them highly sensitive to climate change.

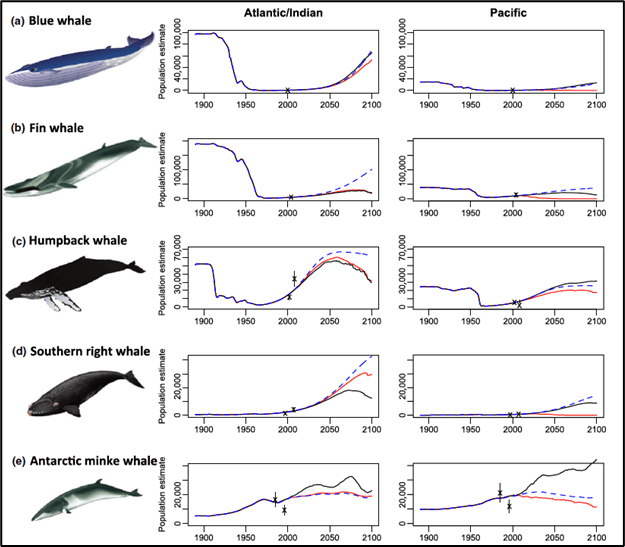

Prior to this study, the researchers developed a model to quantify the impact of historical whaling on the populations of baleen whales (blue, fin, humpback, Antarctic minke and southern right). Their predictions indicated that all the populations of the Southern hemisphere whales were slowly recovering after the ban on whaling. Nonetheless, the recovery rate varied across species. For instance, the humpback whales would reach a full recovery by 2050, whereas the number of blue, fin and southern right whales were projected to only reach half their pre-exploitation numbers by 2100.

The scientists took a step further, and used this model as a baseline to include climate change as a stressor on the whales’ populations. In order to do this, they linked predator-prey interactions between whales and krill/copepods with physical climate drivers such as sea surface temperature (SST) and chlorophyll. The results from this model cast a dark future for the whales. In comparison with their previous model, climate change clearly puts a strong hamper on the recovery of the whale population in the Southern hemisphere. Projections even lead to the local extinction of Pacific populations of blue, fin and southern right whales and the Atlantic/Indian fin and humpback whales by the year 2100. The scientists argue this is directly related with the decline in prey (krill and copepods) and the increase in interspecific competition within whale species.

The model also shows that the decline of krill is more significant in the Pacific Southern Ocean than in the Atlantic or Indian Southern Ocean. This explains the fact that there were more local extinctions observed in the Pacific. In terms of latitudes, the loss of krill biomass was higher in mid-latitudes compared to high latitudes around Antarctica. As a result, the southern right, fin and humpback whales were more impacted as they mainly feed in mid-latitudes, whereas ice-associated whales like the blue whale and the Antarctic minke, preferring to feed in high latitudes, less so.

Finally, the researchers also ran an alternative model to investigate the whale migratory pattern adaptation to future changes in the sea-ice in the Antarctic. For doing this, they included in the model both sea-ice (an additional physical climate driver) and the distribution ranges of whales as variables. This third scenario predicts that the warmer waters and larger ice-free habitat that come with climate change might just keep the head of some whale populations above water, especially ice-associated ones. Due to the warmer polar waters, the distribution of these populations shifted towards the higher altitudes, where there was an increased amount of prey biomass (krill) as a result of a higher abundance of phytoplankton. Nonetheless, the Atlantic/Indian southern right whale population did not seem to benefit from changes in sea-ice, because their distribution remained in the mid-latitudes where the largest prey declines were observed.

Though models are very important tools for conservation efforts and management, we have to remember that they are still a simplified representation of an ecosystem and there is always room for improvements and refinement. For example, the scientists discuss that loss of sea ice could have an effect on juvenile survival (warmer waters means higher survival) and an increased energy expenditure (longer distances to find prey) during migration, though this was not accounted for in the model. In addition to this, the model considered whales to be the only predators of krill, but we know that also seals, penguins, fish, squids, seagulls and humans (commercial catches) consume krill. This could mean that there will not only be competition between whale species, but also with other non-whale species, possibly jeopardizing the whale populations even more. Finally, the researchers consider it an important next step in the future to also incorporate the ice-krill dynamics into their model. Other studies have learned that some krill depend on ice algae for their survival, and it would be ideal to be able to include this interaction.

The prospects for whale populations in the Southern Ocean seem discouraging. So the question remains, what can we do to prevent this outcome? There is no one right answer for this question, and there are different actions that we can do to aid these whales’ recovery. First and most importantly, emissions must be reduced to prevent the effects of climate change. Secondly, non-climate stressors on whales, such as whaling, fishing, pollution and ship strikes, must be kept under control. Thirdly, restrictions on krill catches must be considered to keep their numbers sustainable in the future. By doing so, the resilience of whales under the pressure of climate change could be improved. A joint effort is required by everyone to not let the prediction of the models become a reality, and to help these majestic creatures survive.

References:

Tulloch, V. J., Plagányi, É. E., Matear, R., Brown, C. J., & Richardson, A. J. (2018). Ecosystem modelling to quantify the impact of historical whaling on Southern Hemisphere baleen whales. Fish and Fisheries , 19 (1), 117-137.

Tulloch, V. J., Plagányi, É. E., Brown, C., Richardson, A. J., & Matear, R. (2019). Future recovery of baleen whales is imperiled by climate change. Global change biology , 25 (4), 1263-1281

SHARE THIS ARTICLE