Climate change impacts on shark species across the Globe.

Climate change is one of the biggest threats facing biodiversity today. Among the elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays), freshwater/ estuarine and reef-associated species may be the most vulnerable.

Climate change or more specifically a rise in global sea temperatures will see many shark species shifting their distributions towards the poles, according to a technical report of the project; Pollution and Climate Impacts.

As a result of climate disruption, biodiversity, including marine, freshwater and terrestrial extinction rates are predicted to increase (Fischlin et al

.,2007). Sharks, which are Chondrichthyes or cartilaginous fish are long lived, slow growing species that are late to mature and have low reproduction and mortality rates (Field et al

., 2009). As such sharks are extremely vulnerable to over-exploitation.

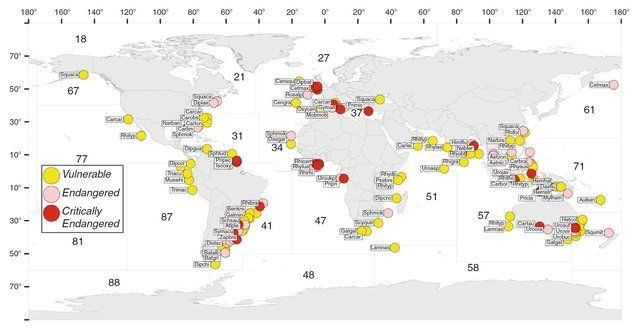

Increased fishing pressure, from targeted fisheries and by-catch, and illegal finning has resulted in several shark species becoming vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered on the IUCN Red List. Climate change is an additional stresses that threatens shark populations around the globe.

Global distribution of distribution of IUCN Red-listed threatened chondrichthyan species (Field et al. 2009; page 312) (see also www.iucnredlist.org ; www.fishbase.org) .

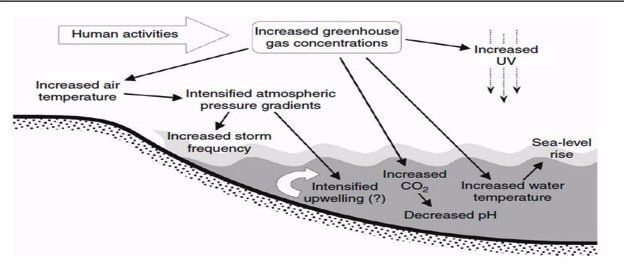

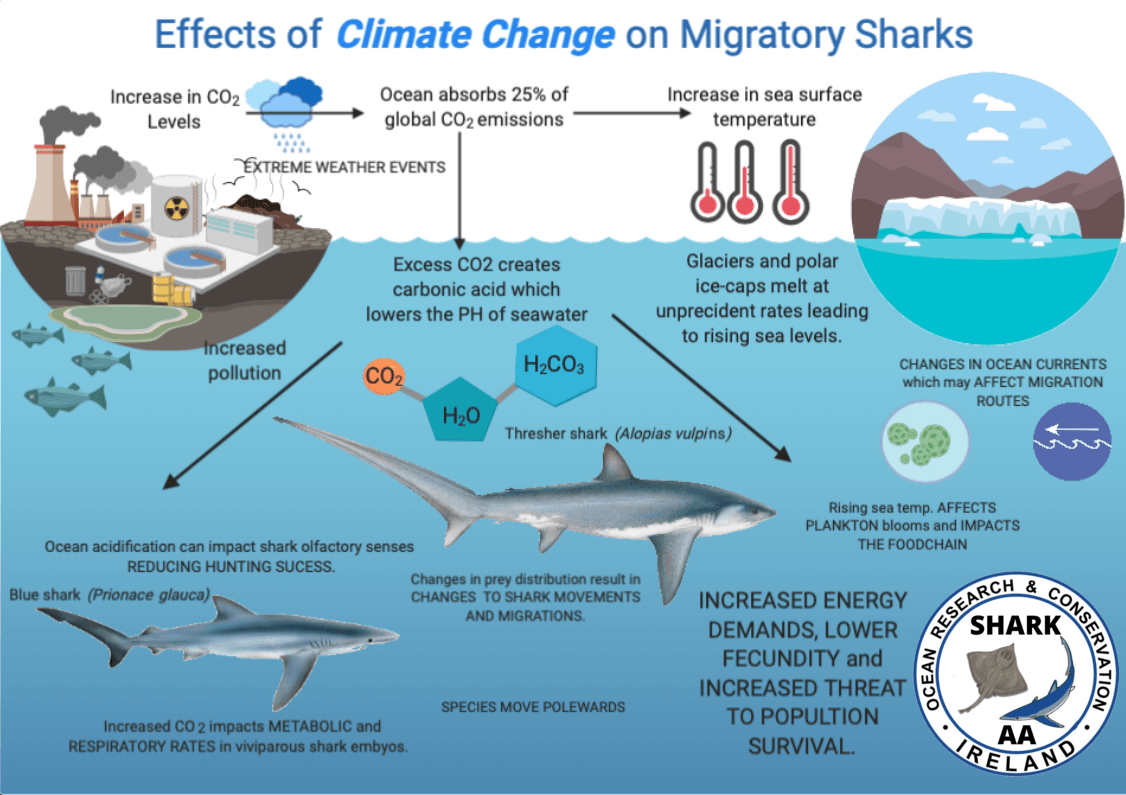

Abiotic changes to oceans predicted from climate change due to burning of fossil fuels and deforestation (Harley et al., 2006).

Climate change has direct and indirect effects on fish communities structure and distribution. Significant effects on marine fishes as a result of rise in sea temperatures, ocean acidification, sea level, and storm frequency/extreme weather events due to climate change can cause changes in movement, catch and growth, northward and deep water shift of species), fishing (increase in fishing costs due to change in fishing locations), corals (coral bleaching), pteropods, and krills (loss of shells), molluscs (reduced calcification, abundance, survival), echinoderms (reduced growth and development), marine mammals (reproduction of cetaceans, shifts in species ranges) (Jennings & Brander 2010; Kibria et al., 2017).

Compared to bony or teleosts fishes, the effect of climate change on elasmobranchs is little known (Graham and Harrod, 2009) however, it appears that temperature may cause major effects on sharks in comparison to other climate change factors such as, ocean acidification, sea-level rise and extreme events.

Sea Temperature:

Among the effects due to the rise in sea temperatures, a significant impact for both fishes and fisheries, is a northward and southward shift in distributions of sharks towards the poles; movement of sharks to deeper waters; alteration or degradation of suitable habitats for sharks ( i.e. seagrass beds, kelp forests, mangroves, coral reefs) and enhancement of bioaccumulation of pollutants.

Although some species such as estuarine and benthic sharks have been shown to have a tolerance for variations in sea temperature, increased temperatures may effect species with a smaller thermal niche, altering their metabolism, behaviour and movement patterns(Fangue & Bennet, 2003; Hoisington & Lowe, 2005; Tullis & Baillie, 2005). Furthermore, an increase in sea temperature would cause a decrease in available dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations in water as oxygen solubility in water is inversely related with temperature and decreased DO concentrations could increase the respiratory stress in sharks. Only few species have a high tolerance for hypoxic (low oxygen) conditions. One such astonishing species, the Epaulette shark, ( Hemiscyllium ocellatum ) is able to tolerate hypoxic (low oxygen) conditions through reducing it's metabolic activity and respiratory rate (Stebbing et al. , 2002; Carlson et al ., 2004).

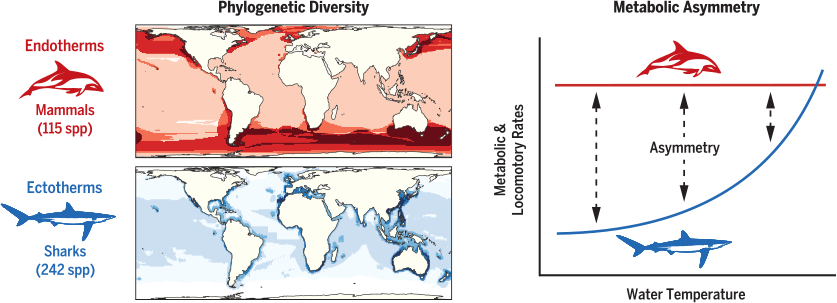

The shift in the many species distributions towards the poles in response to rising sea temperatures will challenge a once solid principal in ecology, that species diversity increases towards the equator. In contrast, for marine species, particularly mammal and bird species richness generally peaks in colder, temperate waters. Also unlike endothermic mammals, ectothermic sharks and fish peak in tropical or subtropical seas. This is linked to the differences in thermoregulatory capabilities between the taxa (Grady et al ., 2019).

Water temperature differences drive variations in metabolism and diversity in marine endotherms and ectotherms. (Grady et al ., 2019)

Ocean Acidification:

Ocean acidification has already had an impact on calcareous flora and fauna (e.g. coral bleaching) (Doney et al. , 2009; Turley et al ., 2010; Kibria et al ., 2016). Corals are important habitat for many reef fishes, which are important prey for several sharks, thus, a decline of reef fishes may limit prey availability and cause changes in species ranges.

Sea Level Rise:

Rising sea levels could damage or destroy many coastal ecosystems including mangroves, salt marshes, seagrasses, beaches, and estuaries. This may limit the availability of the aforementioned habitats to sharks and their prey.

Sea level rise may affect coastal sharks and rays breeding, pupping or feeding due to alteration of shallow water environments.

Extreme weather events:

Extended periods of drought can reduce freshwater inputs and increase the salinity in some intertidal and sub-tidal environments. Similarly, the increase of temperature and higher evaporation will cause a further increase in salinity. While in some parts of the world, heavy rainfall events and floods can reduce salinity in coastal waters. Although some sharks have a large salinity tolerance range, others may be more vulnerable and, the impacts of long-term salinity variations are little known.

The depletion of shark population, can and will cause irreversible alterations to marine ecosystems. As top predators, sharks are keystone species and their loss can contribute to trophic cascades, thus, risks the entire health of an ecosystem. For example, tiger sharks ( Galeocerdo cuvier ) presence has been linked to the quality of seagrass beds through extorting a top down pressure on their prey, dugongs ( Dugong dugon ) and green sea turtles ( Chelonia mydas ), which forage in these beds. Without tiger sharks tocontrol their prey’s foraging, an important habitat will be lost.

Elasmobranch species in Irish waters which may be more vulnerable to climate impacts include species with coastal and shelf ecology such as, mackerel sharks; Lamnidae e.g. the porbeagle shark ( Lamna nasus),

- © Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and www.orcireland.ie , est. 2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland and www.orcireland.ie with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE