Beaked Whales Dive in Synchrony and Silence to Avoid Predators.

Whales that use echolocation for foraging run a greater risk of being detected by eavesdropping predators. New evidence from the North Atlantic and the Ligurian Sea suggests that some species of beaked whales have evolved a unique deep-diving behaviour to hide from their top predators, the Killer whale.

Toothed-whales are experts in using echolocation for communication, navigation and hunting. This allows the animal to create an extremely detailed picture of the world and elegantly exploit their food resources. However, it simultaneously reveals their position to avid and hungry predators. This has led to the evolution of a variety of defences in prey species such as large group sizes in dolphins, or greater social cohesion in sperm whales, or even some species disguising their vocalizations altogether.

Smaller species of the allusive beaked whales, including the Cuvier ( Ziphius cavirostris ) and Blainville whale (Mesoplodon densirostris ), seemingly lacked any predator defence, until now. Beaked whales, belonging to the Ziphiidae family, are one of the least studied mammals on earth due to their deep diving habits, reaching depths of over 500 meters. Unlike other deep diving species, the Cuvier and Blainville beaked whales only make noise during the deepest parts of their dive and ascend horizontally along a low angle rather than straight up to the surface. This has long puzzled researchers as it is unique to these species and is an extremely costly diving style. It was thought that this could potentially lessen the effects of returning to the surface but no physiological evidence for this has been found and other species of beaked whales do not exhibit this behaviour. For instance, the pilot whale ( Globicephala macrorhynchus ) ascend nearly vertically, while the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) calls to its young to help find them at the surface.

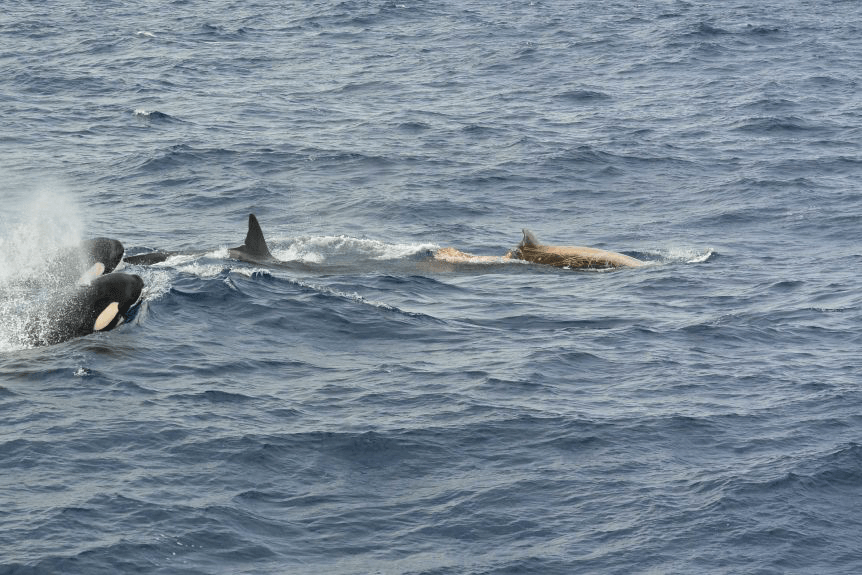

However, due to new research it is thought this bizarre behaviour has evolved to hide from the killer whale (Orcinus orca) . Scientists working off the coast of Italy, the Canary Islands and Terceira tagged a total of twenty-six whales to record information of the depths, movements and sounds of an individual during their dives.

Killer whales tend to hang out at a depth of less than twenty meters and have a limited diving capacity. Therefore, deep waters tend to serve as a refuge for the Cuvier and Blainville beaked whales, allowing for safer foraging via echolocation. Individuals belonging to the same social group showed extreme synchrony in their diving patterns, and only vocally communicating to one another during the deepest points of their dive. On average, 99% of all vocalizations overlapped between whales within their groups and lasted around 26 minutes.

The Cuvier and Blainville whale’s collective during deep dives allow them to make a silent ascent to the surface to breath. However, there is still a small chance predators will be awaiting their arrival at the surface based off their previous vocalizations. The characteristic low angled ascent of these two species allows them to travel distances of over 1km away from the original starting point of the dive. This massively reduces the likelihood of bumping into any killer whales that could have been listening in. Furthermore, killer whales will now have a larger area to search. To make things worse, the killer whale can only do this visually rather than employing echolocation to avoid alerting any potential prey of their presence. Adding in the time-constrains, average swimming speeds and visual acuity, an individual killer whale will only be able to search 1.2% of the total potential surfacing area of the beaked whales.

Such remarkable coordinated activity does have some disadvantages. As all group members dive together, this will inevitably restrict older more experienced individuals. Even young beaked whales have been observed diving alongside adults. This may explain why newborn beaked whale calves are half the size of their mother!

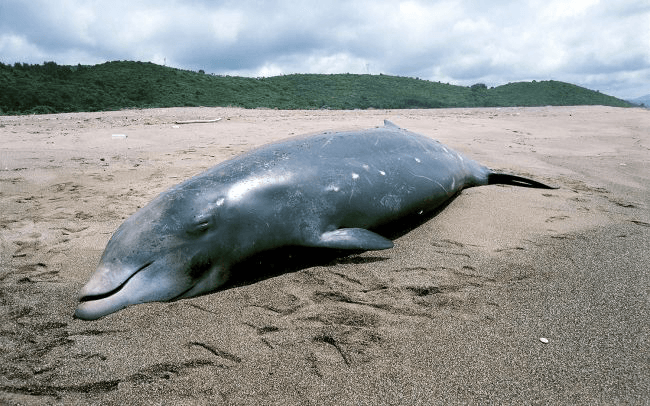

It seems beaked whales have developed clever ways to hide from their predators rather than opting for other fight or flight strategies. However, this once successful defence strategy may play a part in sonar related deaths and mass strandings. As they have little opportunity to predict their risk of predation due to their poor eyesight and the silent hunting style of killer whales, beaked whales react strongly to unusual sounds. Tragically, this can cause them immense physiological distress and ultimately result in death. Looking to the future and the conservation of beaked whales, no sonar should be used in the habitats of these cryptic species.

References:

de Soto, N.A., Visser, F., Tyack, P.L., Alcazar, J., Ruxton, G., Arranz, P., Madsen, P.T. and Johnson, M., 2020. Fear of killer whales drives extreme synchrony in deep diving beaked whales. Scientific Reports , 10 (1), pp.1-9.

Frantzis, A Cuvier's beaked whale, part of a mass stranding that

took place in 1996 in Greece's Kyparissiakos Gulf, LIveScience, Mindy Weisberger

, 30.01.2019 https://www.livescience.com/64635-sonar-beaked-whales-deaths.html

SHARE THIS ARTICLE