A Landscape of Fear: Great-white Shark VS. Killer Whale

Great White Shark VS. Killer Whale

ORCA Sci-Comm Team | June 23rd, 2020.

Predator-prey interactions and top-down ecological control are widely documented across marine systems, but little is known about interactions between large-apex marine predators. The declining and vulnerable Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) population is a highly notorious species that is both desired and feared and is often seen as the ultimate apex predator. A recent research paper suggests that they may have a formidable foe to be feared too - the Killer whale (Orcinus orca). This has potential consequences for conservation efforts of great white sharks.

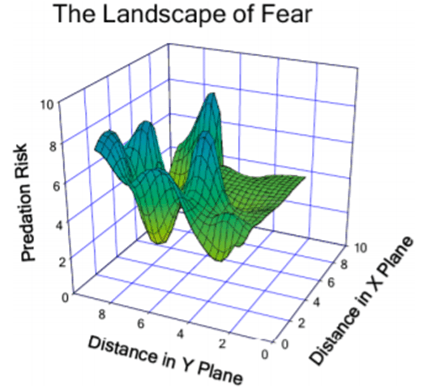

"The landscape of fear" is a unified ecological concept that has developed over the last two decades. It is widely documented in terrestrial (Laundre et al., 2010) and in some marine systems (Wirsing et al., 2008), focusing on prey and predator interactions. A species environment is composed of high to low-risk areas of predation, resulting in alterations of its behaviour to avoid any high risks, with potential cascading ecosystem impacts

Marine top predators, such as large marine mammals and elasmobranchs, are high-trophic consumers, maintaining ocean diversity through top-down control. They have few predators and regulate prey populations through lethal kills and by intimidation. This results in prey altering their behavior, including habitat and foraging strategies in order to avoid risk. However, knowledge of lethal and sub-lethal interactions between marine top predators and their ecological significance is lacking.

A new paper published in

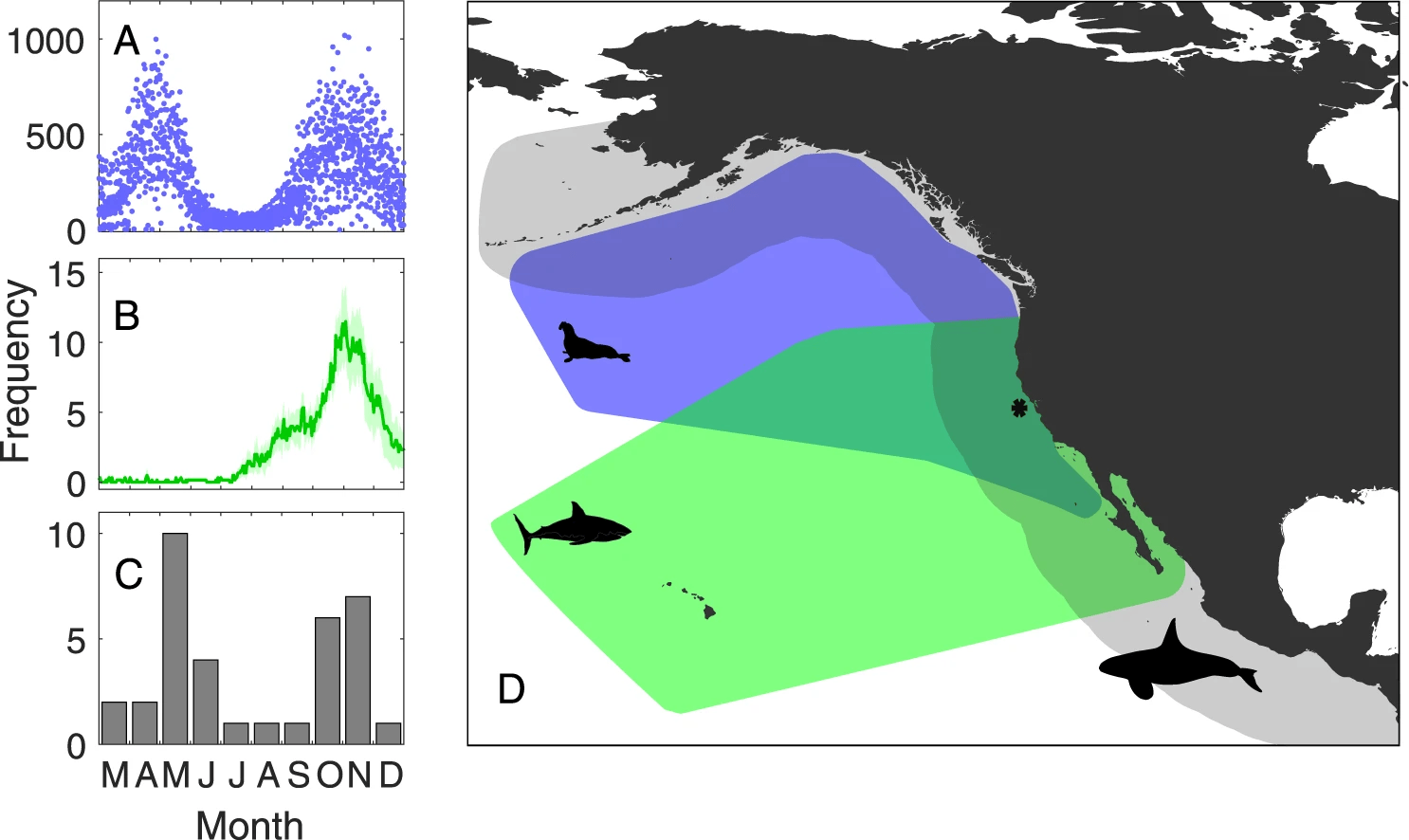

Nature’s Scientific reports, led by Dr. Jorgensen of Monterey Bay Aquarium, compiled observational data over 26 years (1987-2013) around Southeast Farallon Island on the foraging behavior of Great white sharks and the abundance of the Elephant seal and Killer whale populations. This, paired with electronically tracked data of 165 great white sharks (2006-2013) around Central California, enabled the foraging behaviour of the Great white shark population in the presence of the Killer whale be modeled around South Farallon Island.

Based on their analysis, the Great white shark population consistently fled when Killer whales were present within 3km of the shore. They would flee to the extent that they would abandon the site entirely only returning the following season.

These interactions were restricted to the autumnal months, where over 219 Great white sharks are known to prey annually on the juvenile elephant seal population before migrating offshore. The annual predation rate by Great white sharks on these populations in the presence of Killer whales saw a marked dropped of 62%.

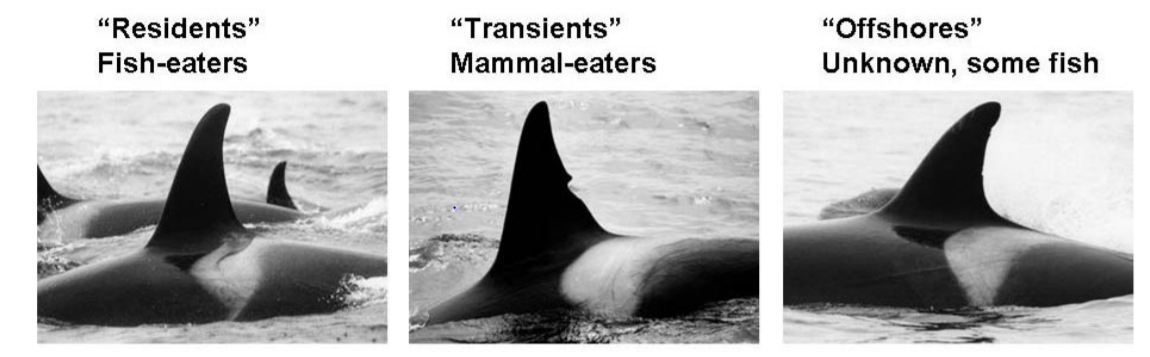

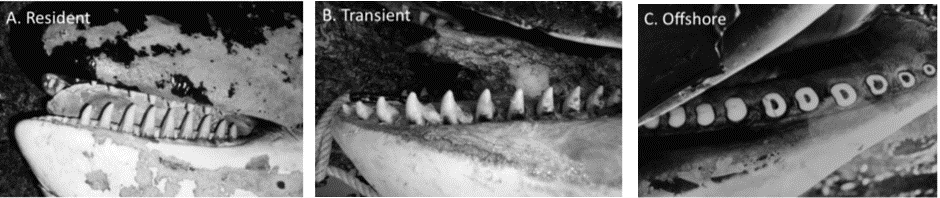

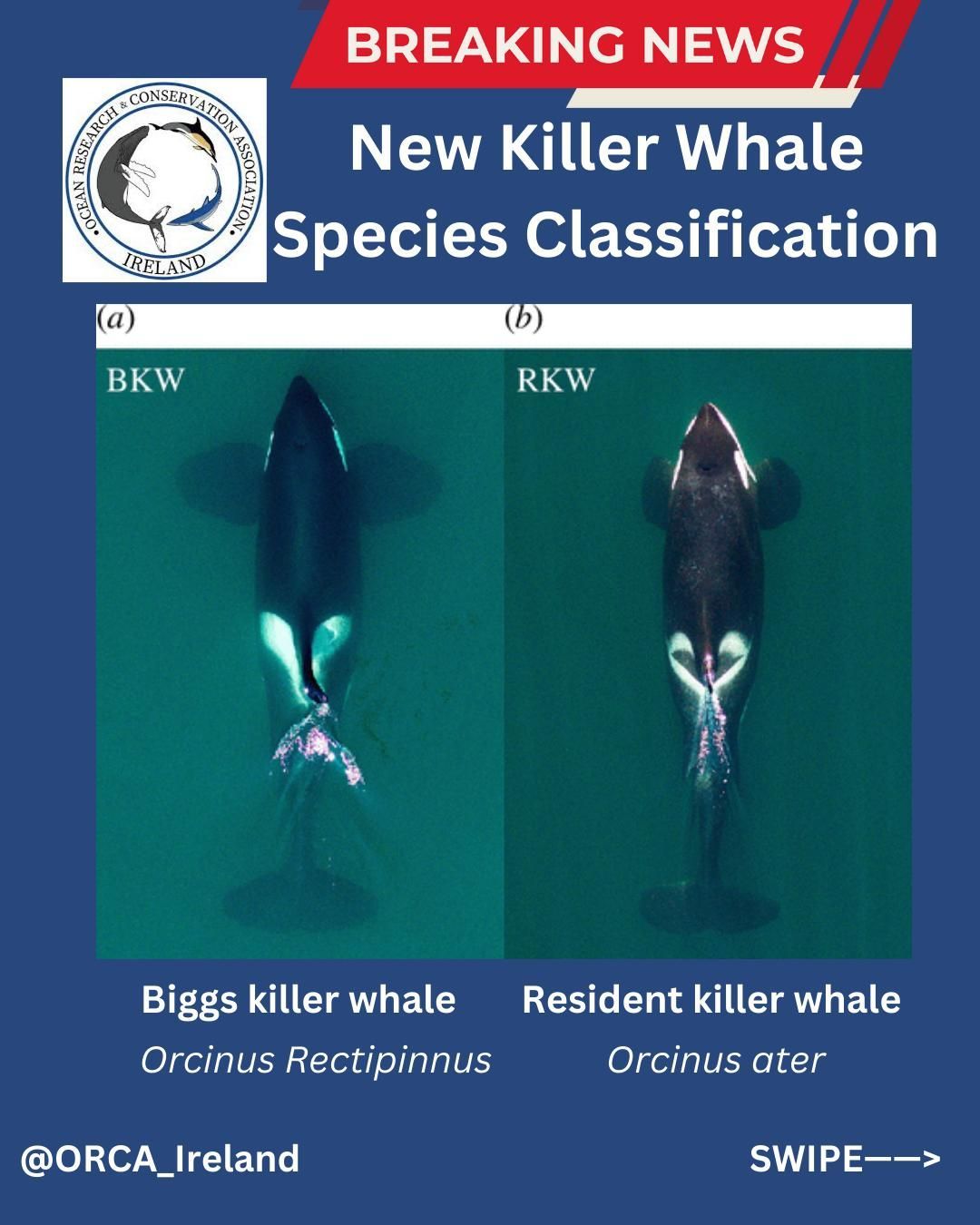

Killer whales are sub-classified into groups of genetically distinct “ecotypes”, with varying diets, communication methods, social structures, and foraging strategies. The most commonly sighted eco-type was the mammal-eating

Transient, with only one occurrence of the

Offshore eco-type in 2009. A total of 18 sightings of Killer whale pods, ranging from 1-17 individuals were present during the autumnal months of years 1992,1995-1998, 2000,2001,2009, and 2013.

The different types of killer whales dictate whether the interactions between the two apex predators are competitive or predatory. The Transient killer whale eco-type is a direct competitor to the Great white shark and the only known Killer whale type to have led to a fatal attack and partial consumption of a Great white shark, recorded in 1997. Meanwhile, the elusive Offshore killer whale eco-type is potentially both a competitor and predator to the Great white shark, indicated by its worn-down teeth and its documented attacks on other shark species.

This paper, through long-term data collection, led to an important discovery on the ecological interactions between two large marine apex predators. In particular, it confirmed that the Killer whale is a threat both as a competitor and predator to the Great white shark. Non-lethal and behavioral mediated mechanisms shape the spatial and temporal use of the habitat and foraging activities of the Great white shark. These behavioral changes bring an inherent risk of reduced foraging ability and fitness before migrating offshore to an already vulnerable species. These interactions have a trickledown effect on lower trophic levels that can be both positive or detrimental to the ecosystem, here, benefiting its prey, the Elephant seal population.

New Paragraph

© Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and www.orcireland.ie , est. 2017. If you like our blogs on the latest news in marine science and would like to support our work, visit www.orcireland.ie to become a member, to volunteer or to make a donation today. This article has been composed based on credible sources.

References:

Eagle, T., Cadrin, S., Caldwell, M., Methot, R. and Nammack, M. 2008. ConservationUnits of Managed Fish, Threatened or Endangered Species, and Marine MammalsReport of a Workshop: February 14-16, 2006 Silver Spring, Maryland.

Ford, J., Ellis, G., Matkin, C., Wetklo, M.,Barrett-Lennard, L. and Withler, R. 2011. Shark predation and tooth wear in apopulation of northeastern Pacific killer whales.

Aquatic Biology ,

11 (3),213-224.

Jorgensen, S., Anderson, S., Ferretti, F., Tietz, J., Chapple, T.,Kanive, P., Bradley, R., Moxley, J. and Block, B. 2019. Killer whalesredistribute white shark foraging pressure on seals. Scientific Reports , 9 (1).

Laundré, J. W.,Hernández, L. and Ripple,W. J.2010. The landscape offear: ecological implications of being afraid. OpenEcology Journal , 3 , 1-7.

Wirsing, A. J., Heithaus, M. R., Frid, A. and Dill, L. M. 2008. Seascapes of fear:evaluating sublethal predator effects experienced and generated by marinemammals. Marine Mammal Science , 24 (1),1-15.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE