Heart rate of blue whale measured for the first time.

A new study has revealed the heart rate of the largest mammal on Earth, the blue whale, which operates at the extremes of physiological capability may limit the whale's size.

A decade ago, marine scientists who attached trackers to emperor penguins ( Aptenodytes forsteri

) at McMurdo Station in Antarctica, while monitoring their heart-rates as the birds dove in the icy waters of the Southern Ocean, got thinking; they could use the same technology on larger marine animals, such blue whales.

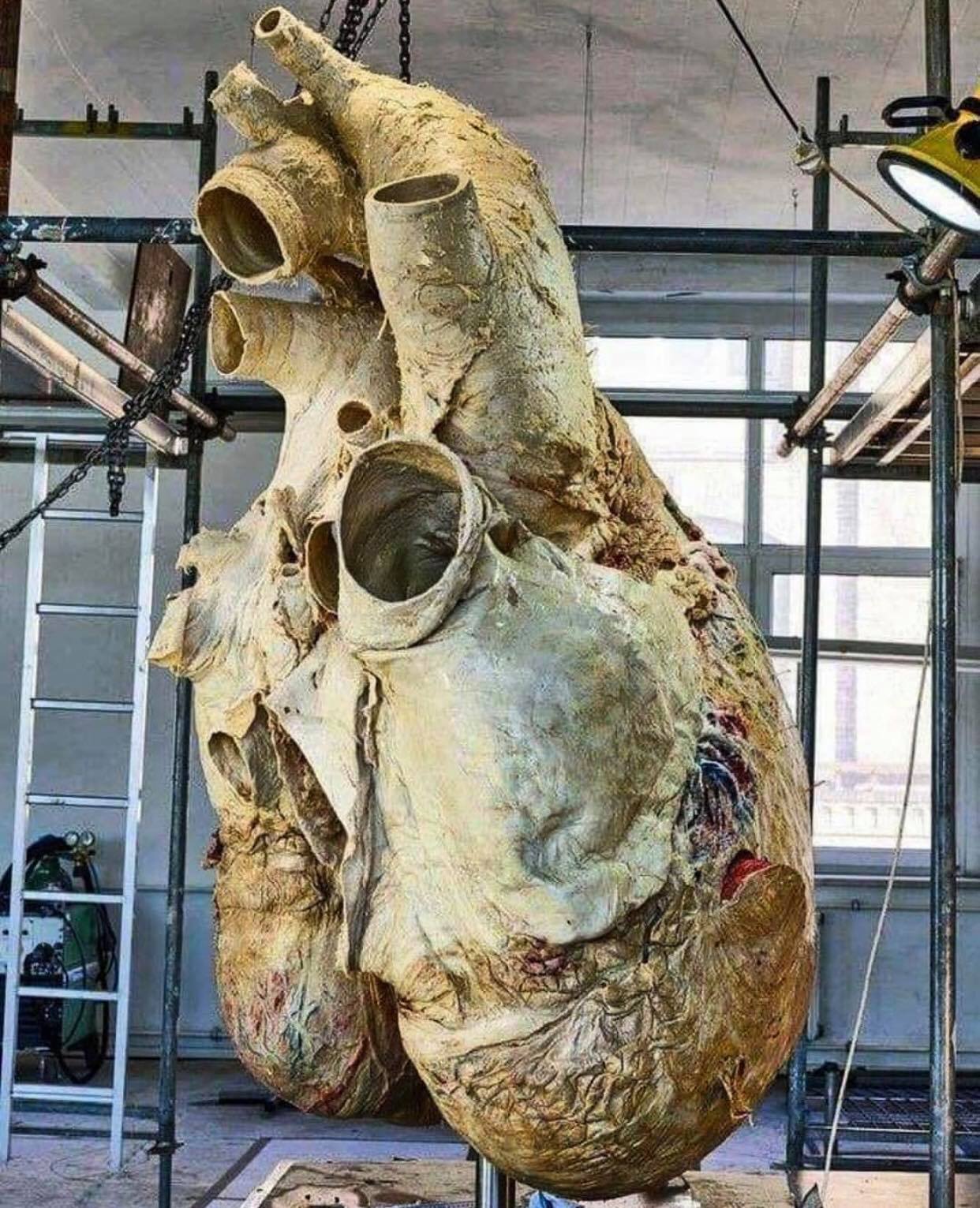

The blue whale is the largest animal that has ever lived and can weigh up to 200 tonnes or 441K pounds, and reach 30 meters in length - the size of an aeroplane or three school buses. The blue whale's heart can weigh up to 180 kg, more than a fully grown cow, but is still only about 1% of the total body weight.

Blue whales have fascinated Marine scientists and anyone lucky enough to encounter the magnificent animal for generations. These whales belong to the Baleen family, so are toothless and instead have baleen, a bristle like structure that hangs from their upper jaw and allows them to filter feed small prey like krill and forage fishes. Baleen is made of keratin, the same substance our fingernails are made of.

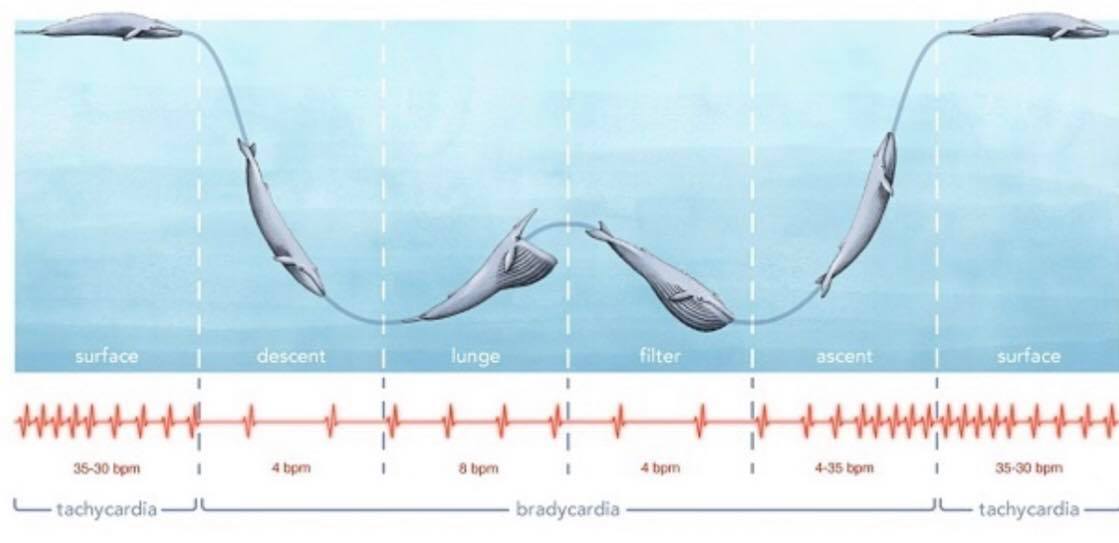

While feeding, whales swim through bait balls or high density areas of prey, engulfing huge amounts of seawater and releasing it through their baleen, filtering their prey. During foraging dives, this new study has been found that blue whales, lower their heart rate.

Generally, larger animals have a slower heart rates. For example, a human's heart rate at rest beats 60 to 100 times each minute. It increases to about 200 beats/ minute during exercise. The smallest mammals, such as shrews, have heart rates of more than 1000 beats per minute.

New research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

has measured the heart rate of a blue whale for the first time! Using an electrocardiogram; a non-invasive suction cup satellite tag with attached electrodes, equipped with a camera; the researchers collected 9 hours of data on a 22-meter-long male from the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California. The researchers connected the special recording device to a long pole and as the whale surfaced to breathe, they quickly deployed the device as close to the animals heart as possible. They successfully attached the device just below the left flipper.

Image credit: Alex Boersma.

Marine Biologist, Jeremy Goldbogen, from Stanford University, led the research team that found that the heart of a blue whale can slow down to just four to eight beats per minute but can be as low as two beats per minute on a deep dive, when the animal is searching for food. The highest heart rate they recorded through-out the study was 25- 37 beats per minute after the whale returned to the surface to breathe and restore its oxygen levels.

According to the official press release, the results were surprising, indicating the whale’s lowest heart rate was 30 to 50% lower than predicted.

The results also revealed that the blue whale’s longest dive duration was 16.5 minutes and reached a depth of >180 meters. The maximum time period the blue whale spent at the sea surface was no longer than 4 minutes.

This study has important implications for understanding the physiological limits of the blue whale’s heart which has been shown to be operating at its limit, which may explain why blue whales have never evolved to be an even larger size. The data also suggested that some anatomical adaptations or unique features of the whale’s heart might, help it perform at these extremes. For example, the scientists concluded that the surprisingly low heart rate could be explained by "an elastic heart" or stretchy aortic arch. The aortic arch functions to move blood out to the body – which, in the case of the blue whale, contracts slowly to maintain additional blood flow in between beats. Interstingly, the extremely high heart rates may be characteristic of the heart’s movement and shape that prevent the pressure waves of each beat from disrupting blood flow.

These research efforts provide fundamental knowledge of the biology large baleen whales and can inform conservation efforts. Furthermore, as the whale’s heart is performing near its limits, the scientists think that this may help explain why no animal has ever been larger than a blue whale – because the energy needs of a larger body would outpace what the heart could sustain.

“Animals that are operating at physiological extremes can help us understand biological limits to size,” said Goldbogen. “They may also be particularly susceptible to changes in their environment that could affect their food supply. Therefore, these studies may have important implications for the conservation and management of endangered species like blue whales.”

Now, the researchers will add more capabilities to the tag, including an accelerometer, which will help them to better understand how different activities or behaviours affect the heart rate.

© Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and www.orcireland.ie , est. 2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland and www.orcireland.ie with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

References:

Goldbogen, J.A., Cade, D.E., Calambokidis, J., Czapanskiy, M. F., Fahlbusch, M. F., Friedlaender, A. S., Gough, W. T., Kahane-Rapport, S. R. Savoca, M. S., Ponganis,K. V. and Ponganis, P. J. (2019). Extreme bradycardia and tachycardia in the world’s largest animal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914273116.

https://news.stanford.edu/press-releases/2019/11/25/first-ever-recorhales-heart-rate/

SHARE THIS ARTICLE