How do humpback whales survive in the marine environment?; Part I

Humpback whales are a perfect example of eco-engineering, designed to travel the globe's oceans from the poles to the equator, covering thousands of miles between important foraging and reproductive grounds, while being able to communicate over long distances, have culture, avoid predators and withstand threats from anthropogenic encroachment on the marine environment. So how do they do it? and what make's these rorquals so fascinating because of their well evolved capabilities?

Humpback whales ( Megaptera novaengliae

) have the longest migration of any mammal on Earth, but how do they do it? Humpbacks have evolved morphological and physiological adaptations to help them survive in the marine environment.

Baleen whales, also known as the "whale-bone" whales or Mysticetes,

are called so appropriately, referring to a key anatomical feature (the baleen plates) that have evolved separately from the Odontocetes

in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) and allow these whales to forage at high efficiency when they do arrive at feeding grounds.

Baleen whales lack teeth and instead have baleen plates, (bristle like structures made of keratin that hang from their upper jaw). While Odontocetes

refer to the toothed whales who do have teeth, e.g. the killer whale ( Orcinus

orca

). Humpback whales have between 270 and 400 pairs of baleen plates, with each one measuring 1 meter in length. Humpback whales use baleen plates to filter-feed. They strategically swim through a bait ball of small fish, i.e. herring or sprat, sometimes in group coordinated synchronicity, and engulf a large mouthful of seawater, using the bristles in their top jaw, they then filter out the unwanted seawater and swallow the prey.

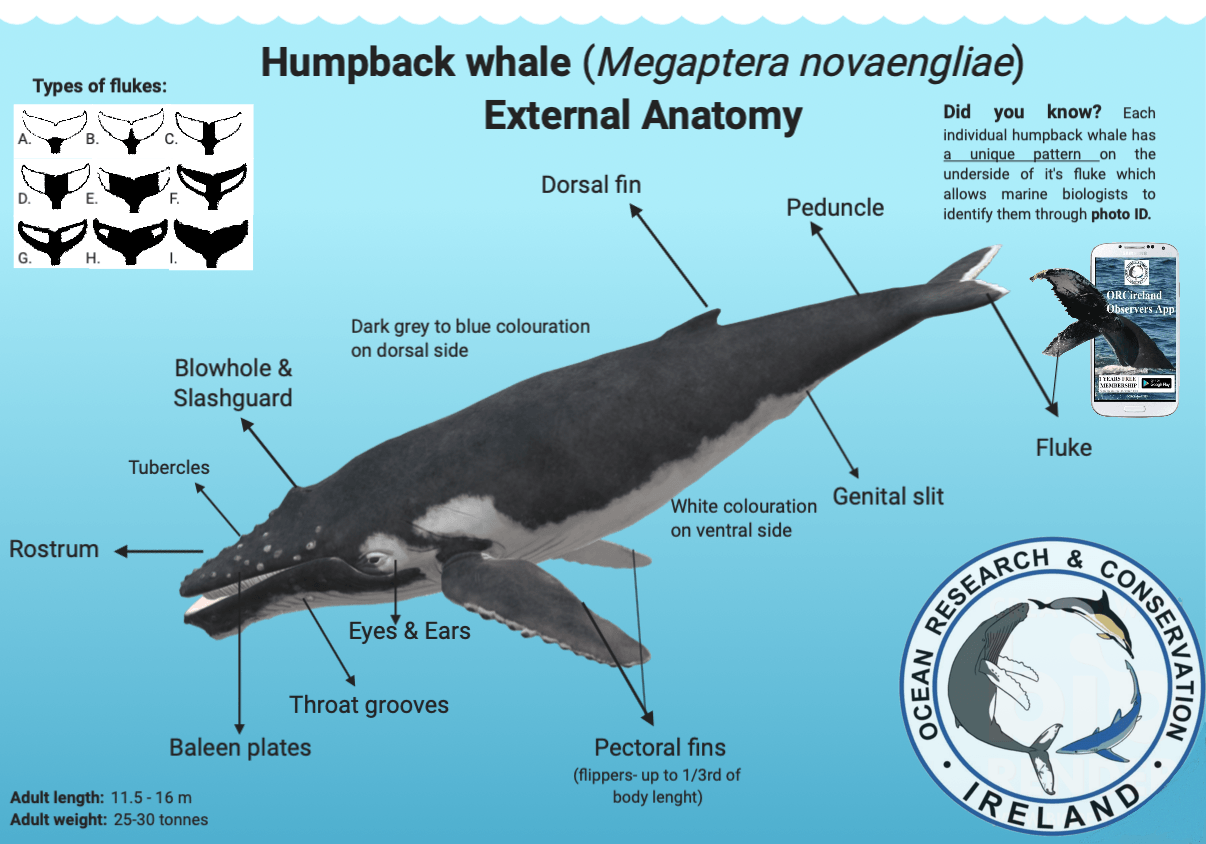

There is currently 15 species of baleen whales described, yet the humpback whale is a species that is world renowned for its elongated pectoral fins or "flippers" that reach up to one third of its body length and can be more than 4.5 m. Humpback whales are also known for their charismatic surface displays or put more simply, what they do with their pectoral fins and their large distinct tail flukes, including "pec-slapping" and "lobtailing". Humpback whales also use their large pectoral fins for steering and stopping while swimming. The humpback’s scientific name, Megaptera, means Big Wings, named so because of their really long pectoral fins.

Flukes are the whale’s tail. Each side of the tail is called a fluke. Humpback whale flukes measure aprox. 5 meters across, which is also one third of their body length. Propulsion is the main function of humpback whales flukes, it allow them to reach speeds of up to over 30 k/hr (16 knots), or more commonly 12 km/hr ( 6 knots) to 20K/hr (10 knots). Every individual humpback whale has a unique black and white pattern on the underside of their flukes which help marine researchers to monitor these endangered animals. Flukes are boneless and are made of muscle and other tissues.

Other adaptations are also useful, including their streamlined, or torpedo-shaped body, allowing them to glide smoothly and easily through the water. Humpback whales exhibit counter-shading in their colouration, i.e. are black on the dorsal, (or upper side), and mottled white and black on the ventral, (or underside).

The humpback whale’s dorsal fin is located about 2/3 of the way down its back. It is pointed and approximately 30 cm long, which is very small compared to the size of the whale’s body. The dorsal fin is used for balance in the water. It helps the whales to stay upright as they swim through the ocean. Scientists also take pictures of dorsal fins to help identify whales. The dorsal fin of each whale has different shapes, colour patterns, and scar markings.

The peduncle muscle is located between the dorsal fin and the flukes. This powerful muscle is used to move the tail up and down for swimming. A humpback whale arches its peduncle when getting ready to dive. This looks like a hump on the back of the whale, which is how the humpback whale got its common name.The peduncle muscle is the strongest muscle in the entire animal kingdom.

The whale’s nostrils are called the blowhole. Baleen whales have two blowholes and these are located on top of the whale’s head near the centre. Whales use blowholes to breathe air at the surface of the water. Toothed whales only have one blowhole. As a whale surfaces to respire, its blowholes open and it exhales and inhales, closing the blowholes again before diving under. The splashguard refers to the area of raised flesh in-front of the blowholes. The splashguards prevents water from pouring into the blowholes when the whale takes a breath. Humpback whales can exhale at over 400 km/hr, creating a blow, or spout, as high as 6 meters.

A humpback’s ears are found internally just behind and below its eyes. The opening to the ear is a very small slit, about a half-inch long. The ear slit is small to help keep water from pouring into the ear. Humpback whales depend on their excellent hearing to find food, avoid danger, and locate other whales and objects in the water. Marine Scientists estimate how old a humpback whale is by looking at its earwax. They remove the plug of earwax and count the layers of wax. The layer built up while the whale is in feeding grounds is darker than the layer that builds up when the whale is on the breeding grounds. This allows scientists to quantify the age of the whale based on how many visits to important habitats it has taken.

The rostrum is also known as the upper jaw or snout of the whale. It is flat and tapers to a point, helping to keep the head streamlined with the body to move through the water easily. Tubercles are bumps found on a humpback whale’s upper and lower jaws. Each tubercle has a half-inch long hair, called a vibrissa. Scientists are not sure why humpbacks have tubercles, but think they are used to sense temperature and vibrations in the water. Humpbacks are the only whales with tubercles.

Ventral pleats are long grooves on the underside of the whale’s throat that run from the chin all the way to the navel. Ventral pleats allow the whale to expand its mouth three times its normal size during feeding. This helps the whale to capture large amounts of food in one giant gulp. Humpback whales have 12–30 ventral pleats. Male humpback whales gulp in water to expand their ventral pleats. This makes them look larger and more impressive when competing with other males in the breeding grounds.

Want to know how you can help humpback whales and become an #OceanHero / citizen scientist? Use your phone for good! Take photos and videos of any humpback whale you see and send them to us using the Observers App available for Android on Google Play. Get a years free membership and stay up to date by receiving our E-letter.

How do humpback whales survive in the marine environment; Part II. Coming soon.......

© Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland (ORCireland) and www.orcireland.ie , est. 2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ocean Research & Conservation Ireland and www.orcireland.ie with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE